Does gerrymandering contribute to polarization?

In the July tradition of summer camps past, let’s play Two Truths and a Lie: Gerrymander Edition. Ready? Guess the lie:

1. Based on national votes cast for them, Democrats should have 18 more seats — a three seat majority — not the 33 seat minority engineered through Republican gerrymandering.

2. Eight of today’s ten most gerrymandered districts were drawn by Republican legislatures.

3. Nine out of those ten most gerrymandered districts benefit Democrats.

If you’ve been following national gerrymandering from the left, #3 is clearly false. Republicans have undeniably engaged in crafty redistricting plans more (#2), and it follows that the practice clearly doesn’t benefit Democrats, who have lost their majority (#1).

In fact, they’re all true, including #3. The most egregiously gerrymandered districts — especially the ones drawn by Republicans — benefit Democrats the most. But how can that be?

The answer has to do with gerrymandering’s long-suspected, but never proven, relation to polarization. The political community has debated this issue for years, producing widely varying answers. But at least part of the reason is a misconception about gerrymandering, and what gerrymandering ultimately does.

A Very Gerrymandered Misconception

Gerrymandering is the phenomenon of manipulating the Congressional redistricting process. With every Census, all 50 state legislatures are required to redraw the borders of their congressional districts to accord with the Supreme Court’s “one person, one vote” rule and to make the districts as equally populous as possible. While the exercise is premised on equality, it presents an irresistible opportunity for political parties to tilt the playing field to their advantage. The party that controls the state legislature inevitably redraws the districts, with patchworks and shapes so bizarre that their creators nearly join the pantheon of postmodern art. The retooling of these boundaries boils down to one purpose: to maximize the number of seats their party can capture in the upcoming election. Bewildered by the complexity of other options, the Supreme Court has mostly upheld this arrangement.

The common misconception — even President Obama has fallen prey to this error — is to assume that gerrymandering allows parties to engineer safe districts for their incumbents, ensuring easy reelection. But the exact opposite is true. Redistricting’s real purpose is engineering safe districts for your opponent — to pack as many of them into as few districts as possible. It’s like Patton’s infamous maxim on war: you make the other poor bastard die for his country. If anything, redistricting by conservatives would make Republican House districts slightly less conservative in order to include Republican voters in districts where their votes are needed to win seats.

That’s exactly what Republican state legislatures — exactly seven of them, by one analysis — have done. Of the 10 most gerrymandered districts in America, according to an analysis by The Washington Post, nine are Democratic strongholds. Gerrymandering employs two main tactics: “packing,” or stuffing your opponents into as few districts as possible; and “cracking,” or taking the remaining scattered enclaves of opposition, splitting them in half and melting them into separate larger districts. (Incidentally, the dictionary of gerrymandering is long and hilarious). We think of gerrymandering primarily as “cracking,” but successful redistricting requires both techniques to stack the odds.

This makes sense when you zoom out to the state level. Take North Carolina, roughly level with Maryland as the most gerrymandered state in America, for example. In Maryland, redistricting by a Democratic legislature has helped grow a slim 5-4 majority in the congressional delegation into a clear 7-1 advantage. North Carolina has observed a similar if more rapid process, yet there the three most Democratic districts are also the most gerrymandered districts. But in 2010, before the redistricting, North Carolina’s congressional delegation was 7-6 Democratic. After redistricting, Republicans transformed that proportion into a 7-4 advantage (the state itself lost seats due to population changes). The Republican state legislature achieved this reversal by making those four Democratic seats extremely safe — so safe, in fact, that the average percentage of victory in 2012 for gerrymandered districts was 76 percent. The average Republican percentage of victory in North Carolina, however, actually diminished after redistricting, from 80 percent to 62 percent.

But today, people treat gerrymandering as the apparent product of politicians’ desires for sizable, gorge-like majorities. In fact, the opposite is true. It may seem like a small distinction, but it actually has an enormous impact on the public psychology of electoral reform.

The Great Debate

At the moment, gerrymandering is at the center of an intriguing debate in the political class: does gerrymandering cause polarization? After all, both have risen to unprecedented levels.

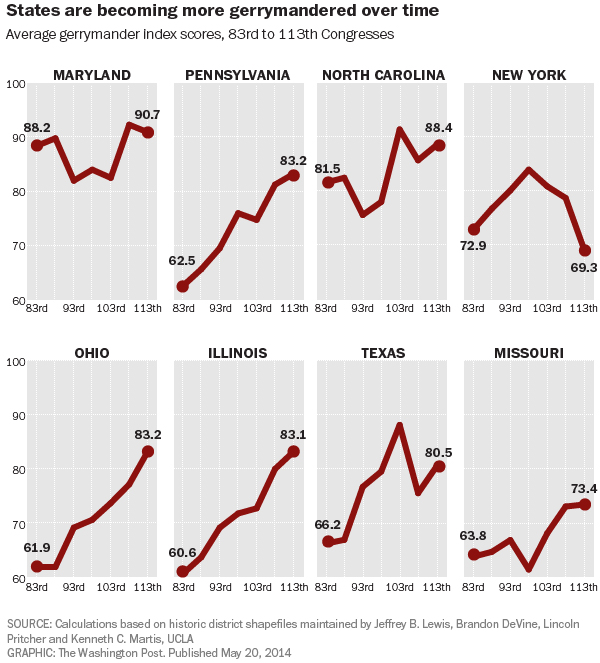

Does this graph, which shows a rise in gerrymandering in various states…

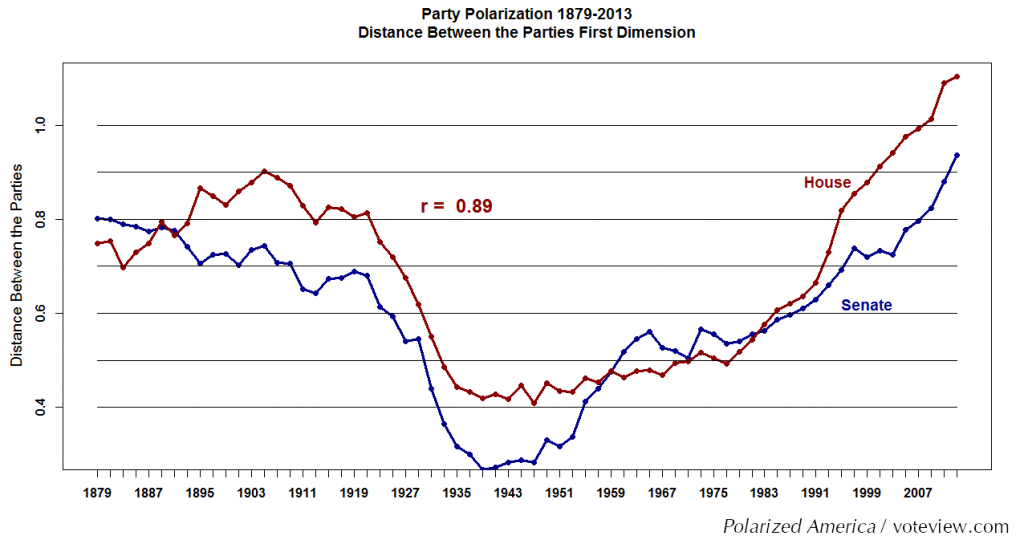

…cause this graph, which shows the rise of polarization in the House and Senate?

Let’s imagine two sides to this debate: the Gerriers (pronounced exactly as you imagine) and the Anti-Gerriers. Each side has a detailed argument to make their case, but their real difference lies in their modus operandi. Gerriers tend to look at political incentives; Anti-Gerriers see polarization elsewhere in society.

Let’s start with the Gerriers. They claim that gerrymandering causes polarization, or at least contributes to it, for a number of reasons. The mainstay of their logic is that polarization is best exemplified by Congressional action, and that incentives for voters and their representatives are the main culprit for this effect. These are some of their reasons for why gerrymandering creates this polarization:

1) By “cracking” constituencies and fusing them into unrepresentative districts, gerrymandering “disenfranchises” voters by rendering their ballots meaningless and diminishes confidence in democratic processes (sometimes known as “political efficacy”). This is the competitive view: districts should have as competitive elections as possible, so that the winner is more moderate.

2) It splits apart communities or regions that have similar interests and ought to be served by the same representation, creating municipal rivalries for federal resources.

3) Most importantly, as the argument goes, it parcels the state into ideological camps, preventing the kind of dialogue and reconciliation that some say used to define our civic tradition. Without the mitigating effect of a moderate constituency, Congresspersons who represent these ideological strongholds themselves have less reason to compromise thus making Congress more partisan.

Taken together, for Gerriers these consequences of redistricting explain why Americans hate Congress in record numbers, but 90% of Congresspersons are nonetheless reelected. For while each district coexists with their elected representative in strong ideological harmony, Congress becomes supposedly ever more dysfunctional as the political aisle grows wider and wider.

This Gerrier logic makes sense, in a circumstantial way. Yet the reaction from the Anti-Gerriers has been swift. The driving theme of their critique is that polarization exists as more than just a record of legislative action: it’s a cultural phenomenon that exists outside of lines drawn on a map. As George Washington University’s John Sides aptly puts it, polarization is about “people, not polygons.” The Anti-Gerrier’s arguments extend further:

1) Political scientists point out that political partisans tend to live in areas dominated by candidates with whom they already agree, a decades-long phenomenon that has to do with American culture, not redistricting. It’s not clear that taking polarized, self-segregated communities and forcing them into the same district would somehow diminish partisan hatred, and could plausibly increase it.

2) Another study imagined voting behavior based on simulations that created more “neutral” redistricting plans compared to the gerrymandered ones we have now. In each scenario, the polarization trends were still comparable – vindicating the idea that the causes of polarization continue to exist whether states employ gerrymandering or not.

3) Professor Sides has pointed out that polarization trends are mirrored in the Senate, where the seats of course cannot be ‘redistricted.’ Again, this polarization in the Senate hints that something else, not gerrymandering, is causing polarization.

4) Redistricting can’t explain polls that show Republicans have a growing aversion to compromise in theory, an aversion liberals do not share, according to the Pew Research Center. Primary elections that appeal to a more extreme ‘base’ of partisan voters in every district, whether gerrymandered or not, could then be a more likely culprit for polarization.

5) Gerrymandering doesn’t explain Republican polarization, the more dominant driving force of American polarization. After all, how could it? The biggest point is this: Republicans have made their districts, all other things being equal, slightly less safe for themselves, districts that are certainly less safe than their ‘packed’ Democratic counterparts.

Each side in this debate has well-reasoned and detailed rationale. But in these two bullet summaries, one theme jumps out. Gerriers and Anti-Gerriers certainly disagree on the merits of gerrymandering, but the core of their disagreement is about something else: their worldviews. Gerriers see polarization fundamentally as a function of how we vote. Anti-Gerriers see how we act, not how we vote, as the principal behavior. Is polarization a cultural creation, or a political phenomenon?

For now, the consensus from political science has dealt a clean victory to the Anti-Gerriers, a class of eager Moneyballers perhaps too quick to marshal data sets and simulations. But Anti-Gerriers have issued a reprisal worthy only of the fallaciousness of their adversaries: by debating political incentives and cultural developments, we’ve asked the wrong question. It is, in effect, the blind leading the deaf.

The Anti-Gerriers have convincingly shown that gerrymandering isn’t causing polarization, but in the process they may have overlooked something important: inequality, in many senses polarization’s evil twin. Increasingly, these two horsemen of American decline are capturing the imagination of political scientists and economists, who have begun to study how the phenomena are linked. Not without coincidence, polarization and inequality are also where politics and culture clash. If political scientists considered this connection, gerrymandering need not link directly to polarization in order to contribute to it. Instead, it would need only to link to inequality, where the connection becomes possible by the second degree.

How Gerrymandering Could Contribute to Polarization

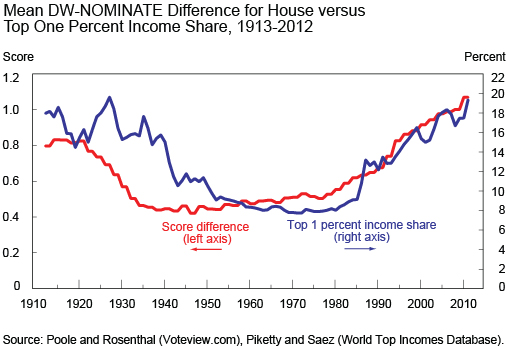

It turns out that the link could plausibly exist, and become worthy of deeper exploration. Gerrymandering, that is, could have a lot to do with inequality. It is a conclusion that numerous academics and observers have begun to reach: Increased political polarization does, in fact, correlate to heightened inequality, and vice versa. Extensive and growing research — from Princeton to Georgetown, behavioral economics to city politics, mainstream journalism to the Federal Reserve — all prove or point to this same correlative connection. Here is the marquee chart from the New York Federal Reserve Board showing how upward shifts in polarization predict upward shifts in inequality:

One theory for this correlation, advanced by the Federal Reserve Bank of New York, is that political polarization prevents Congress from acting on economic issues, especially ones directly concerning inequality. The minimum wage is just one example of a highly popular policy designed to counteract inequities that has seen no action in Congress.

Other interpretations seek greater complexity with their analyses. As journalist Ezra Klein beautifully explains, voting tendencies in Congress no longer accord to voter preferences, in that Congressional action remains at identical levels whether public support for a given policy is at 10 percent or 90 percent. Instead, Congressional tendencies are now best predicted by third parties — action groups, nonprofits, for-profits, PACs, Super PACs, unions — that donate campaign contributions.

These organizations wield their power by donating greater and greater sums of cash during federal election cycles. The total price tag for 2012 election contributions was $6.3 billion — the highest ever. The next highest was four years prior, and the next highest four years before that, and so on and so forth — with nonpresidential election years also experiencing steady growth. Specifically, campaign contributions tend to find their way to incumbents, who possess a major advantage in fundraising. Whether incumbents win or lose, they typically spend the most on elections. They also spend unprecedented amounts of time raising money during their time in office.

And gerrymandering, by design, creates incumbents. The predictive power and capture of campaign finance colludes with gerrymandering, whether via “cracking” or “packing.” In newly captured districts (created by cracking), serious challengers require extra fundraising prowess just to meet parity with their gerrymandered incumbents — money that is less likely to come from citizen constituents since they constitute such a marked minority in the district. Even in party strongholds (created by packing), where virtually no challenger could succeed, the warping effect of campaign finance is felt — through the rising phenomenon of candidate-to-candidate giving. Candidates with excess cash are permitted to donate it to any candidate they choose, creating a strong incentive for incumbents, even in “packed” districts, to fundraise like there’s no tomorrow, in order to build up political chits. If gerrymandering produces a diminution of citizen faith in the democratic process, it would plausibly discourage constituents from donating to their congressional campaign or any other, further diminishing the incentive for Congresspersons to act in accordance with voter preferences (as Klein found).

Finally, the fact that our redistricting system affords redistricting power to state legislatures in the first place adds a new dimension to the campaign finance wars. As part of a nationwide conservative plan to redraw House districts across the country, Project REDMAP spent $30 million on state elections, alongside other corporate-aligned interested groups like the Koch brothers. We might imagine that the same finance-driven force that straightens out Klein’s graph will soon exert the same affect on state legislatures, exacerbating inequality. Remember how Sides disproved the gerrymander-polarization connection — that polarization in the House mimics the Senate? The biggest difference between the House and Senate is that only the former faces redistricting. But the gerrymander-inequality connection stands on the same logic: the New York Fed study found that polarization in the House correlates more closely with inequality than in the Senate.

This is the heart of why we misunderstand gerrymandering, as a debate between voting behavior and American culture. Gerriers think gerrymandering makes seats “safer,” when it fact the data tells us it makes majority party districts slightly less safe; But this is a contradiction only if you believe district “safety” has to do solely with votes. Anti-Gerriers think political polarization happens outside of gerrymandering, in American culture; but this works only if the opinions of citizens have a manifestation among elected officials. It doesn’t; they barely do. Safety, in the new era of campaign finance, is about fundraising and money, and the opinions that have agency are the ones behind the names who sign the checks — not about votes, and not about opinion.

This missed connection is often hiding in plain sight. Reporter (and Gerrier) Dave Weigel highlights a particularly conservative Congressman, Rep. Jim Jordan (R-Ohio), and contends that his behavior is a product of his gerrymandered district, a notion that Anti-Gerrier and New York Times reporter Nate Cohn refutes. After all, Cohn says, Jordan’s district is slightly less red than otherwise (just like North Carolina). Yet Jordan feels more “safe” politically. Why? Weigel casually stumbles upon the critical detail without fully exploring it:

Jordan ran ahead of Romney, easily dispatching a union organizer who raised $34,167 to Jordan’s $1,078,119.

Congressman Jordan feels safer because he is safer — because he sits on committees whose business concerns powerful interest groups. Because those interest groups donate to anyone who sits on those committees, a privilege of incumbency. Because Congressman Jordan receives those donations. Congressman Jordan feels safer despite losing Republican votes because political safety in elections has little to do with votes.

Weigel’s accidentally-correct reporting sums up the idea here. The Gerriers are potentially right that gerrymandering worsens polarization, but wrong to diagnose gerrymandering in and of itself as the problem. It’s the incumbency that gerrymandering perpetuates — both packed and cracked — that worsens polarization by attracting campaign money and thus heightening inequality.

There’s one important drawback to this idea. Would some kind of gerrymandering reform realistically mitigate inequality, and therefore polarization? To redraw every district as a 50-50 toss up would probably make the situation worse: every race soon a life-or-death black hole of national money. And with the Supreme Court’s recent decision in McCutcheon v. Federal Election Commission, there’s no limit to how much influence a single person could exert throughout unlimited elections across the country.

Even though the connection may be strong between gerrymandering and inequality, its purpose may only be to shed light on a larger truth. After California instituted its own attempt to thwart gerrymandering — instituting “nonpartisan” district review boards that attempted to draw “fair” districts — the following election was the most expensive on record, and polarization still increased. These are two facts that should not be read separately. California’s gerrymandering reform produced a more proportionate congressional delegation, but that’s about all it did, while inequality and polarization remain rampant. Moreover, the supposedly nonpartisan commission quickly became the target of political maneuvering by the state’s Democratic establishment. The two horsemen still ride in California.

Gerrymandering may be linked to inequality, and therefore to polarization, but it’s not clear that correcting gerrymandering would solve those problems. To the extent that it could, there may be only one solution: deliberately drawing congressional districts for the sole purpose of alleviating inequality, or, if you’ll excuse, “Fair-e-mandering.” Such districts would have lines that twist and contort in the interest of linking the poorest slums with the most garish McMansions. Incumbents, then, would at least have to face the whole spectrum of income in the same proverbial town hall. Then again, given the exertion of campaign finance, we know whom Congressman McMansion would tune out as soon as the proverbial Town Hall were underway.

Perhaps that’s the lesson here. In a political reality where campaign finance is utterly dominant, gerrymandering may not be the villain some good government reformers make it out to be. But it is almost certainly an accomplice to the crime.