On February 5, the Rhode Island House Committee on Health, Education and Welfare heard testimony from supporters of a bill that would equip all public schools in Rhode Island with Narcan, the “miracle” drug capable of rapidly reversing opiate overdoses. I’ve seen Narcan administered as an EMT, and the results are astounding: an unresponsive patient suddenly begins to breathe again. Narcan doesn’t cause a high, and it has no potential for abuse. Indisputably, Narcan has the potential to save lives, and Rhode Island is in dire need of opiate overdose prevention measures (the state ranks thirteenth in the country for most overdose fatalities, with 17.4 deaths per 100,000 people annually). However, the bill faces its share of critics. The modest availability of state funding for Narcan kits prompts some to believe that this drug might be more effectively implemented elsewhere—in the hands of police or emergency responders instead of school nurses. Others feel that the widespread distribution of Narcan may actually incentivize opiate usage by giving users a “free pass,” allowing them to pursue a bigger high without the fear of a fatal overdose. Narcan can save the lives of students in Rhode Island public schools—but equipping schools with the drug should not be the state’s highest priority.

The bill that would put Narcan in schools is the latest in a string of legislative actions aimed to address steadily rising overdose deaths in Rhode Island; since 2009, overdose deaths have doubled. Annually, more Rhode Islanders die from drug overdoses than from car accidents. These killer opiates — a group of narcotics that includes heroin as well as prescription drugs like Oxycodone and Percocet — work by binding to opiate receptors in the brain and depressing the central nervous system, relaxing the body. People die when their bodies become so relaxed that they forget to breath. According to the Rhode Island Department of Health (HEALTH), 232 people died in Rhode Island of accidental drug overdoses in 2014; in the first three weeks of 2015, seven people died from overdosing. Health officials blame the ready availability of heroin (which can be purchased for as little as $5 in Providence) and heroin laced with fentanyl, a powerful painkiller, for the spike in overdose deaths. In the past four years, heroin has become a national scourge — and Rhode Island is an epicenter of the new epidemic.

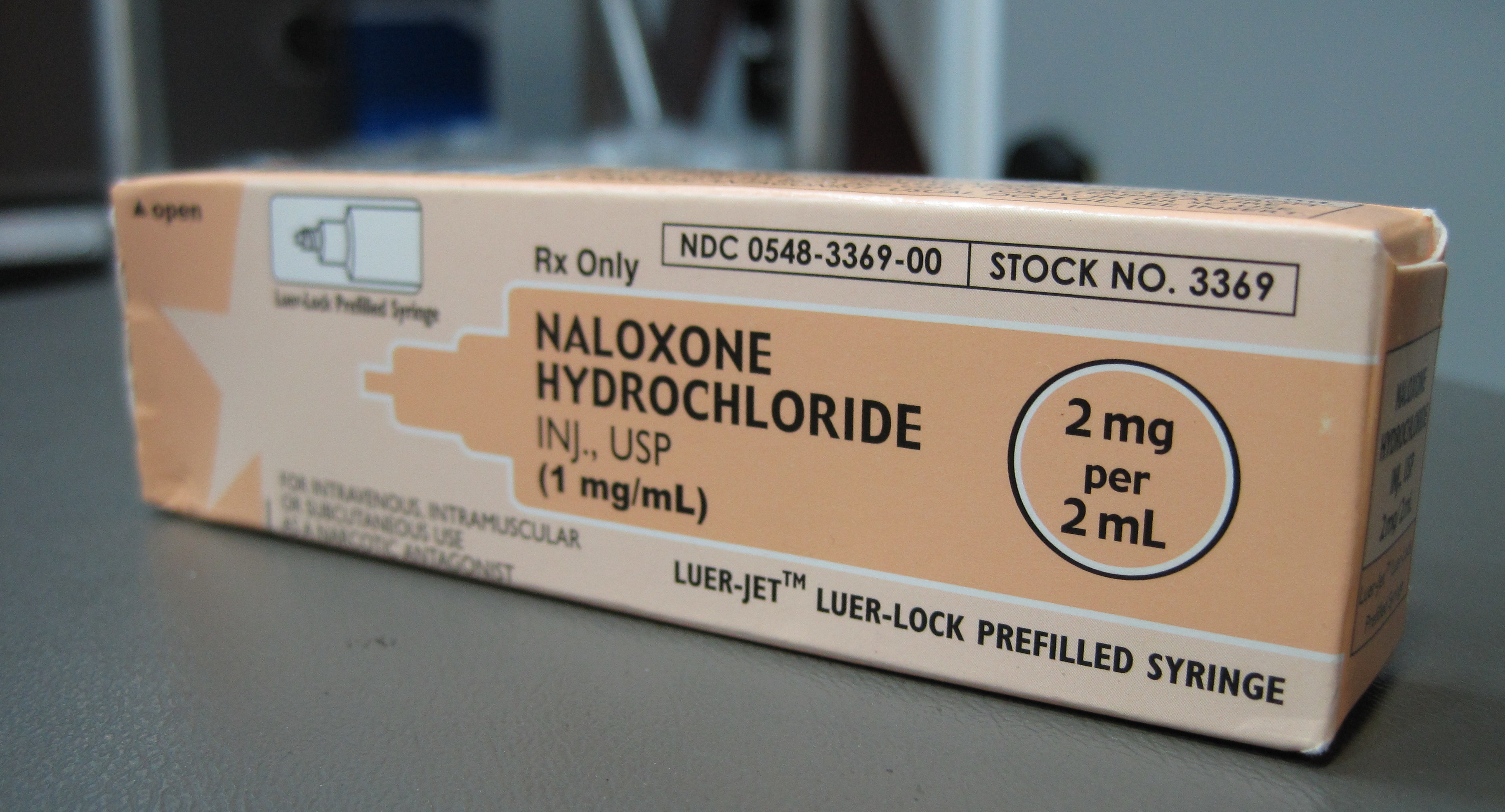

In the past few years, lawmakers, hospitals and pharmacies have teamed up to expand the availability of Narcan, an opiate antagonist that removes opiates from the brain’s receptors and prevents them from binding, kicking the respiratory drive back into gear. In 2012, Good Samaritan Laws were passed that decrease liability for lay organizations and lay people who administer Narcan in the case of a suspected overdose. In 2013, Walgreens began offering Narcan without a prescription to anyone who wanted it as part of a collaborative agreement between Miriam Hospital, the pharmacy and HEALTH. In 2014, CVS followed suit, and several police departments (including the Rhode Island State Police) began carrying Narcan kits. All police officers in participating departments were trained in administering Narcan as a nasal spray in any case of a suspected overdose, and last year HEALTH reported that police officers administered over 150 doses of Narcan—so far in 2015, the need for Narcan hasn’t let up. The new bill, proposed after a HEALTH survey of 81 school nurses indicated a growing concern about opiate use in schools, would require that school nurses receive similar training and that all public schools stock at least one dose of Narcan. Several nurses reported already having called 911 for suspected overdoses in school, though no confirmed overdoses in public schools have been reported by HEALTH. If a trained nurse saved a student from death by accidental overdose with a school-supplied dose of Narcan, the bill would seem justified, but the almost four Rhode Islanders dying of opiate overdoses every week aren’t overdosing while in school.

Cost has already been a major obstacle in providing Narcan to law enforcement and community outreach organizations, and objections to the bill have largely centered around its fiscal implications — David A. Bennett, who introduced the new bill, estimated that the cost of supplying schools with Narcan and training school nurses would be about $7000. However, The New York Times recently reported a sharp spike in Narcan prices, coinciding with increased demand for the drug. The kits that cost the Rhode Island State Police $35.50 may now cost as much as $60 each — and each contains only one dose of Narcan, which may not even be enough in some instances of overdose. To field the cost of supplying Narcan to first responders, the state of Rhode Island has had to get creative: the state dipped into last year’s $500 million fine from Google. “People are getting creative,” said Traci Green, assistant professor of epidemiology and emergency medicine at Brown. “What sets RI apart in this endeavor is that it really has — from the beginning — had to approach overdose prevention from a point of sustainability. Having $0 for prevention and training, the state has succeeded in getting naloxone out there, we just need a lot more of it!”

Because only two companies in the country manufacture Narcan (and only one of them manufactures it for the use of emergency responders), the price is unlikely to drop anytime soon. The Rhode Island state budget is $15,000,000 short as of 2014 — and the funds available for Narcan distribution would be best diverted toward the community organizations and first responders most likely to come into contact with high-risk groups. While adolescent opiate use is acknowledged as a rising concern, the group most affected by opiate overdose deaths is males aged 25-40 — secondary school-aged children are the lowest-risk group in Rhode Island, though GoLocalProv recently reported that first responders used Narcan 50 times on minors last year.

Others see state or federally funded distribution of Narcan as a tacit endorsement of drug use by the government. In Maine, Governor LaPage has vowed to thwart legislative attempts to make Narcan more accessible or put Narcan in public schools. In Connecticut, legislation similar to the Rhode Island bill has been rejected. While all CDC studies on the subject agree that Narcan distribution is not linked to increased opiate use, the question may be moral as much as practical. How much should taxpayers support those who choose to use illicit substances or abuse their prescribed medication? Emergency responders — EMTs, doctors, and policemen—aren’t trained to evaluate the moral justifications of the people they try to help. They are trained to try and save every life that they can — which, more and more, means administering Narcan. The question isn’t whether Narcan should be in schools — because it can save lives, it absolutely should be — but whether or not Narcan in schools can or should be the state of Rhode Island’s top priority. The most at-risk users aren’t in public schools; they are adults, living on their own or with family, and people most likely to reverse their overdose in time are the police who respond to the scene or family members of the user. These groups, who have the most potential to save a life in an overdose scenario, will benefit from Narcan the most if it’s distributed to police departments and community outreach centers.

While the Rhode Island bill has the potential to save the life of a student or staff member who has overdosed on opiates, it also raises questions of resource distribution in the state’s efforts to quell the rising flood of overdoses and overdose deaths.