April is a hopeful month for policymakers, activists, and citizens around the globe aspiring to address the multiple problems surrounding the international drug prohibition regime. From April 19 to 21, the United Nations will convene its much-awaited Special Session on Drugs at the headquarters of the organization in New York City. The Session will provide a unique opportunity for international actors to shed light on the limitations of the current paradigm of drug policy worldwide and to put forward the necessary alternatives. Last held in 1998, the United Nations General Assembly Special Session on Drugs, or UNGASS, is aimed at the total eradication of drug consumption and production at a global scale. But unlike the previous session, the 2016 UNGASS comes at a time when growing consensus is developing among leaders and civil society groups around the need to re-evaluate old policies and to consider alternative, less punitive approaches that emphasize harm-reduction instead of criminalization. For representatives of communities who have directly faced the consequences of the prohibition regime — either through mass incarceration, environmental degradation, militarization or human right abuses — the upcoming UNGASS is also a unique chance to demand justice from world leaders.

The history of the international drug prohibition regime is grim and troubling. Back in 1971, US President Richard Nixon declared drugs to be “America’s public enemy number one,” and thus launched a campaign aimed at completely eliminating illicit drug consumption and production. With the beginning of the so-called “War on Drugs,” his administration shifted the focus of drug abuse from a health problem to a national security concern and began the criminalization and incarceration of drug users, now considered offenders. But following the logic that consumption could not be eradicated without dismantling the entire drug market, the Nixon administration also established harsh measures to tackle production, trafficking and distribution. Because the cultivation and manufacturing of illicit substances had been prohibited in the United States for decades, drugs primarily flowed into the country from countries in the Caribbean and South America where enforcement was lax. Because of these flows, the US government determined that the domestic eradication of the drugs required a transnational effort. US foreign aid packages now contained a budget for eradication efforts. In Latin America, particularly in Central America, Colombia and Mexico, “war on drugs” strategies translated into militarization by recipients of US aid. In response to the increasing strength of drug cartels and gangs in the region, governments opted for deploying militarized police and army personnel in their own territories to engage in warfare against criminal enterprises. Over the past few decades of these policies, the effort has failed to achieve the goal of reducing drug abuse and instead has had devastating unintended consequences throughout the hemisphere.

In both the United States and Latin America, marginalized communities of color are the ones paying the high human costs of drug policies resulting in criminalization, incarceration and militarization. For instance, drug offenses are the main reason for imprisonment in the United States. These policies are a central contributing factor to mass incarceration and are one of the main reasons the US has the highest incarceration rate in the world. In a system plagued by structural racism, punitive drug policies disproportionately affect communities of color. According to the US Bureau of Justice Statistics, even though people of color comprise only 30 percent of the nation’s population, they represent 60 percent of prison inmates, and are more likely to receive harsh sentences than their white counterparts. The statistics are particularly chilling for the male African-American population, as one in three African-America men can expect to go to prison at least once in his lifetime.

Mass incarceration extends south of the United States’ border: In drug-transit countries, like Central American and Mexico, a majority of inmates in these countries’ prisons have sentences relating to drug offenses, and alarming number of prisons are overcrowded. And yet, in Latin America, mass incarceration is only one of many devastating unintended consequences stemming from drug prohibition. The US demand for cocaine, marijuana and poppy is so high and dependent on Latin America that it has altered the region’s agricultural production: In some states in Mexico like Michoacan and Guerrero, socially marginalized farmers, left with no other viable option for economic subsistence, are increasingly turning to highly lucrative marijuana and poppy cultivation.

But perhaps the most damaging aspect of the “war on drugs” in Latin America is the emphasis on pro-militarization policies and the violence this has brought about. Colombia and Mexico have witnessed, albeit in different time periods, skyrocketing homicide rates and human rights violations as a result of drug-war policies. The statistics are chilling: confrontations between criminal groups (cartels or gangs) and state forces have internally displaced 6 million in Colombia, led to the enforced disappearance of 26,000 Mexicans, and made Central America the region with the highest homicide rate in the world. In both Mexico and Colombia, this violence has in part been fueled by a militarized approach to policing, supported by US-funded initiatives like Plan Colombia or Mexico’s Merida Initiative.

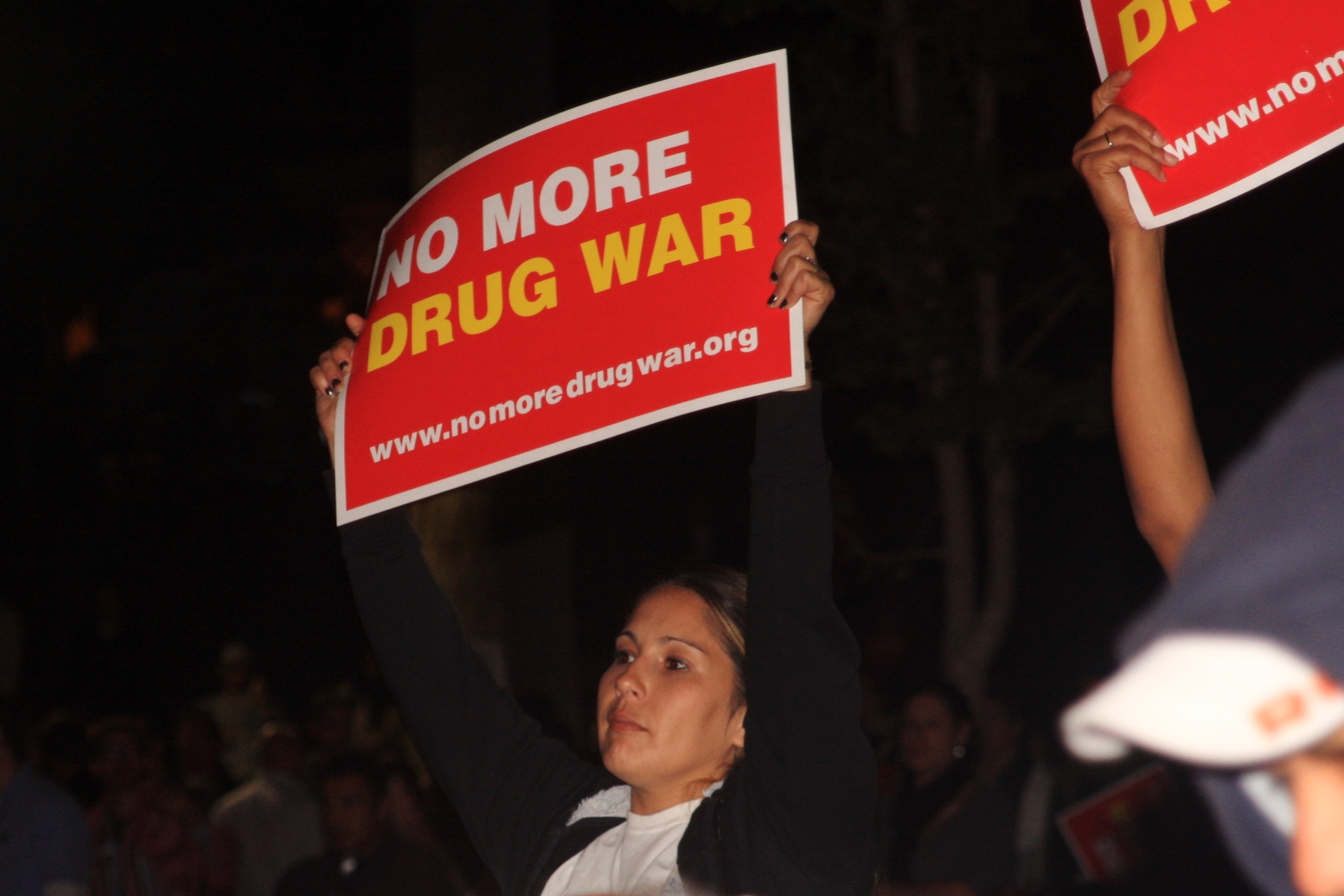

As the harmful effects of the drug prohibition regime have become more evident over time, leaders, policy-makers and community activists in the region have mobilized to demand drug policy reform. For example, the Latin American Commission on Drugs and Democracy, comprised of a number of regional leaders, scholars and former heads of state, is a key group pushing for drug policy alternatives focusing on harm-reduction and minimization of potential human costs. In the United States, NGOs such as the Drug Policy Alliance and Support Don’t Punish have long campaigned against the ¨war on drugs¨ and have been key actors in advancing the legalization of marijuana in a number of US states. Families whose loved ones have disappeared or been killed in as a result of drug-related violence in Latin America continue to pressure their governments with constant protests. In Mexico, the call for an end to the Mexican Drug War spurred the formation of a national movement, the Movement for Justice and Peace with Dignity, which, in 2011, led former President Felipe Calderón to acknowledge the victims of the policies he had implemented.

All these actors, along with hundreds of other activists, will be present at the UNGASS demanding an end to the prohibition regime. In an unprecedented opportunity, the UNGASS will provide a platform for pro-drug policy actors to unify their call for change. Taking into account the complexity of the prohibition regime, advocates will push for alternative policies at all levels of the drug supply chain. From marijuana legalization proposals for US states, to calls for de-militarization in Mexico and environmental campaigns from indigenous groups, the international civil society is prepared to present alternatives aimed at reducing harm around drug production and consumption. As it is the case with other UN-hosted events, governments around the globe will closely follow the discussions, and the Session’s resolution will serve to inform local policies in the future. Although the UNGASS may not guarantee a change in drug policy at governmental level, it is certainly a powerful international space, arguably one with great political leverage, with the potential to influence positive change.

The session and civil society forums in the days leading up to the event will be first steps in the necessary effort to acknowledge the victims of a drug regime, which costs thousands of lives of color in the Western hemisphere every year. In response to an international drug regime founded on racism and feeding on a cycle of violence, it is important to support the initiatives that are looking to reverse the damage and that protect our communities.