At the John Wayne Museum in Winterset, Iowa — a museum entirely devoted to commemorating the late, notorious actor — Donald Trump stood in front of a fake desert background and a wax figure of John Wayne. “When you think about it, John Wayne represented strength, he represented power, he represented what the people are looking [for] today because we have exactly the opposite of John Wayne right now in this country,” Trump said to the crowd surrounding him. He was accepting an endorsement from Aissa Wayne, John Wayne’s daughter. In her announcement, Aissa Wayne not only supporting him, but added that if her father, who died from cancer in 1979, were alive, he’d be “standing right there” alongside Trump.

John Wayne has been associated with conservative values for decades: he was a staunch supporter of President Nixon, and he was so vocal about his anti-communist views that Stalin apparently considered assassinating him. Yet, almost immediately following Aissa Wayne’s endorsement, his son disavowed the Trump campaign. Ethan Wayne, who also serves as the President of John Wayne Enterprises, released a statement saying, “John Wayne Enterprises and John Wayne Cancer Foundation wish to state that Aissa Wayne acted independently of both organizations and the Wayne family in her endorsement of Donald Trump…No one can speak on behalf of John Wayne and neither the family nor the foundation endorses candidates in his name.”

In doing so, John Wayne Enterprises seems to be distancing its namesake’s legacy from political matters, choosing instead to focus on anti-cancer initiatives and other charity work. This move follows a pattern that emerged after John Wayne’s death, one that celebrates Wayne as an American icon who transcends politics — Wayne’s image has been sanitized and continues to be by those that have a vested interest in his legacy. This pattern is in line with the country as a whole’s short-term memory in approaching difficult issues — rather than confront the problematic beliefs of historical figures, we have a tendency to think of them as a product of their time and dismiss any problematic beliefs as such.

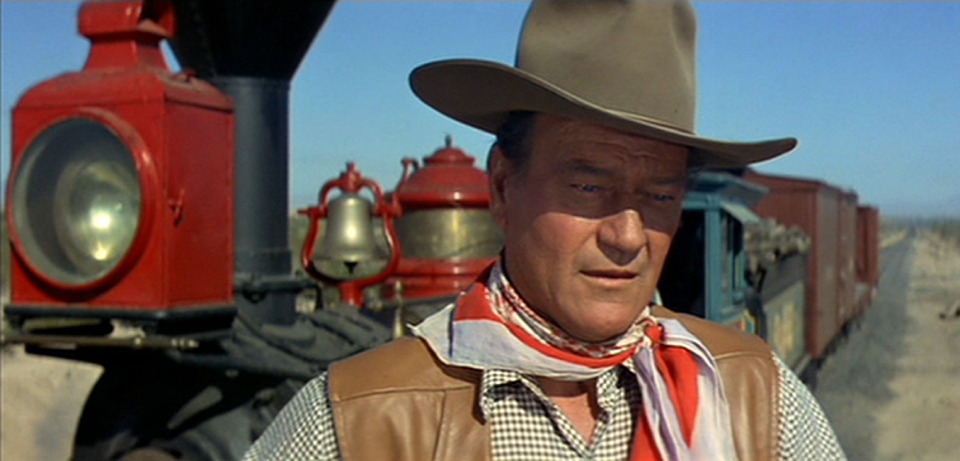

Whether John Wayne would have been “standing right there” alongside Trump is unknowable, but looking back at Wayne’s career sheds some light on the issue. The Searchers, made in 1956, has been cited as one of, if not the, best Westerns of all time, maintaining a 100 percent rating on Rotten Tomatoes and consistently ranking among the best films ever made. The film follows Ethan, a former Confederate soldier played by John Wayne, as he searches for his niece who has been kidnapped by the Comanche Tribe. He’s driven not by his resolve to save her but rather to his determination to kill her — she’s been living with (and presumably has had sex with) Native Americans, and so she deserves to die. The issue is explicitly racialized: when Ethan encounters another set of women who are traumatized after being kidnapped by Native Americans, he remarks, “They’re not white anymore.”

It’s hard to say if the film is meant to be critical of this racism, an issue that film critics have struggled with since its release. In a 2001 review of the film, critic Roger Ebert asked, “Is the film intended to endorse their attitudes, or to dramatize and regret them? Today we see it through enlightened eyes, but in 1956 many audiences accepted its harsh view of Indians.” Ebert, and some other modern critics, have come down on the progressive and optimistic side, arguing that the film is actually critical of the racism that underlies many Westerns. Yet, given the way in which the film was received at the time, it’s hard to discern whether this is simply a modern sanitization of the film’s original intent.

Furthermore, Wayne’s personal beliefs suggest that his own relationship to race was somewhat fraught. In an interview for Playboy in 1971, Wayne said, “I believe in white supremacy until the blacks are educated to a point of responsibility.” On the subject of Native Americans, he said, “I don’t feel we did wrong in taking this great country away from them, if that’s what you’re asking. Our so-called stealing of this country from them was just a matter of survival. There were great numbers of people who needed new land, and the Indians were selfishly trying to keep it for themselves.” Supporters of Wayne have suggested that these statements are a product of their time and that Wayne was no more racist than any of his contemporaries. Yet, looking back at the original interview, its clear that this wasn’t the case. The interviewer repeatedly confronted Wayne, asking, for instance, if Wayne agreed that there were educational inequities preventing the upward mobility of people of color, to which Wayne responded, “What good would it do to register anybody in a class of higher algebra or calculus if they haven’t learned to count? There has to be a standard. I don’t feel guilty about the fact that five or 10 generations ago these people were slaves.” After the interview was published Wayne was criticized for these statements, which were rightly seen as racist and ignorant, suggesting that Wayne was not simply a product of his time, but rather an especially political and controversial figure.

The sanitization of John Wayne possibly began around the time of his death. When Congress was deciding whether to give Wayne the Congressional Gold Medal several weeks before he died, Robert Aldrich, the President of the Director’s Guild of America, said, “It is important for you to know that I am a registered Democrat and, to my knowledge, share none of the political views espoused by Duke. However, whether he is ill disposed or healthy, John Wayne is far beyond the normal political sharp shooting in this community.” Aldrich’s need to mention his own political leanings suggest that Wayne was viewed as an inherently political figure, but that, given his illness, he should no longer be viewed in such terms.

This trend has continued, as suggested by John Wayne Enterprises’ refusal to endorse Trump as a candidate. Yet, Aissa Wayne’s endorsement is a reminder that Wayne has not always been an American figure who has risen above politics — throughout his lifetime, he was outspokenly conservative and, at times, racist.

Despite this sanitization, Wayne’s cult following is in part due to his controversial views — his fans buy into a specific view of America fraught with racial and gendered connotations. By covering up these views, they don’t go away, they just become less explicit. In this way, Wayne’s sanitization echoes Trump’s own political strategy. Though, like Wayne, Trump has at times been explicitly racist, he also relies on subtext to attract his supporters. His slogan, “Make America Great Again,” for instance appeals to the majority of his supporters who think America has gotten worse for “people like them” in the last fifty years — fifty years that were filled with progress on civil rights and gender issues.

In the wake of Aissa Wayne’s endorsement, a conservative blogger wrote, “Wayne stands for something so much more than just his remarkable body of work…Just the fact that the endorsement meant something to Trump is yet another reminder that, if nothing else, this Manhattan billionaire cares about what we are about — he gets us.” The blogger didn’t elaborate on what exactly Wayne’s image represents, but its political significance was clear — the subtext of Wayne’s legacy still has political capital, even if John Wayne Enterprises is attempting to suppress it.

The blogger also wrote that the endorsement was met “by our media overlords either with dismissal or this kind of snark and outright hate.” In a world where the media — and political parties themselves — are viewed as hostile, subtext is necessary to appeal to supporters. By sanitizing Wayne’s image, John Wayne Enterprises has attempted to maintain his popularity among a vast majority of fans, but Wayne’s legacy can still be called upon by politicians like Trump to meet political objectives. Though the sanitization of Wayne’s legacy suggests that America has a short memory when it comes to its legendary figures, it also suggests that that memory differs — for some, John Wayne represents a harmless part of America’s past, and for others a necessarily political one.

Stopped reading after “Wayne’s World”… what a travesty to use this to describe the legacy of the Duke.