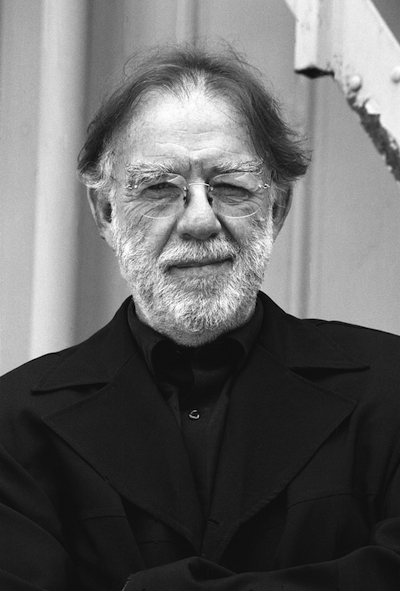

Godfrey Reggio is a contemporary documentary filmmaker who has pioneered a distinct film style interlaying visual images with soaring scores. Born in New Orleans in 1940, Reggio spent 14 years a monk of the Christian Brothers, a Roman Catholic pontifical order. In years subsequent, he has used the medium of film to explore the destructive consequences of our technological environment.

What is the message of your films? What are you attempting to say with them?

My films are autodidactic experiences as opposed to most other films which are based in literature, the spoken word, the popular form of cinema that tells you a story, a plot. But in my films, there is no overt literary form, so there is no plot as such. The person sitting next to you could have a vastly different experience because we’re not telling you what to think. The meaning is in the form and you’re free to have your own point of view about it. That’s what I mean by autodidactic. We construct the image by synthesizing the visual and aural so that you see the score through the image and the image through the score. What you get from the film is what you get from the film.

That is something I’ve experienced myself — each time I’ve watched Koyaanisqatsi, for example, I’ve seen a different beauty in it depending on where I’ve been in my life.

Well, it’s like taking any journey into the woods or onto the beach or up the mountain. You’re just there for the ride. You’re taking it in. It’s like if you were with your sweetheart and you saw a sunset and you asked her “what is the meaning of the sunset?” It’s a ridiculous question, but can the sunset be meaningful? Indeed. That’s the meaning we’re trying to provide when we make these films. They can’t be categorized. People call them experimental which I think is ridiculous because they’re experiential. Each person brings their own experience to the to event.

That said, the subject of the film, if you want to look at it in the grossest way, is a new and comprehensive environment that is hidden in plain sight. Technology. And rather than using literature to question what technology means, we use the very medium technology itself to give an experience of what it means to live in a technological environment. Being human we’ve become the environment we live in.

You named the titles of your first three films after the Hopi words “Koyaanisqatsi” (life out of balance), Powaqqatsi (parasitic way of life), Naqoyqatsi (life as war). What is your opinion of the state of the world today given the Hopi vision of a meaningful reality?

I’m not a Hopi devotee, nor am I someone trying to be a Hopi, but in the Hopi language I found a perspicacity that was not in my English language. I felt that their words described the world we live in more accurately than any words that I could find. I still feel our language doesn’t adequately describe our world. We live in a world where the moment of the truth is the moment of false. What is the condition of the world? It’s unspeakable. Like a frog in water, the water might be cool when the frog gets in but by the time it’s boiling, it’s all over and he still doesn’t know it. That’s the situation we face today. The world we live in is not perceived by us. We are technology because it is the air we breathe. Technology is in the driver’s seat and how we’re strapped in for the ride. In that sense Facebook, Microsoft, Apple et al. are more dangerous than al-Qaeda.

The previous film you made, Visitors, continues the Qatsi Trilogy’s exploration of technology. What were you hoping to achieve with it?

I wanted to make the film a reciprocal gaze beginning with a shot of the eyes of a Trishka, the gorilla, who sets the modality of the film. Most of it is extremely slow. I guess the critical response to this film has been it’s the most expensive screensaver ever. It was not well received. Having said that I loved the film. I look at films like children. This kid has autism. Koyaanisqatsi? That kid was on speed. He was hyperactive. So they’re different kind of kids. I think at some point, or hope, that that film will continue to live in its own form one day.

Rewatching Visitors last night, I realized that the long shots of the people’s gazes were shot through a mirror system, so the kids were actually watching the screens as you filmed them.

Yes, many of the children were playing video games. The younger children were watching things like Dumbo. It didn’t matter — as soon as the TV set went on, it was like a radical attractor. Boom.

Did you tell them to kind of act natural?

No, I didn’t tell them anything. That would have been phony. So it’s just being able to film them in a situation where they lose self-consciousness because they don’t see us. They just see the screen. I was looking for an authentic response.

Are you familiar with Baudrillard?

I liked a lecture he gave called The Evil Demon of Images. It’s quite a challenge but it’s probably available somewhere on the gizmo. It’s a little bitty book but I’ve found his work provocative.

I bring a Baudrillard up because see a lot of similarity between your work and Baudrillard’s idea of hyperreality where nothing is real anymore, and our images structure our reality. There’s that long commercial in Naqoyqatsi you include, for example — the one of the family getting pizza. In that commercial, everyone is smiling, but nothing is real, and even family relations are contrived.

Well, those images are unending they’re like the wallpaper of our life. They’re ubiquitous and inescapable. I remember the first time I went to the Soviet Union. I was so shocked when I saw that there wasn’t any commercial commodity advertising. But here it’s it’s hidden in plain sight. It’s stated so ubiquitously that you don’t notice it anymore. But it notices you.

Do you watch conventional Hollywood movies?

Very very few if any. My only interest is to stay completely focused on what I’m trying to do because it’s quite a heavy lift. I’m obsessed that way. I’m totally focused on trying to create something.

Do you use the Internet?

Oh no. I have in front of me my analog computer of 72 boxes, or what you would call apps. I don’t use a computer. I don’t use the Internet. I’m an addictive kind of person I’d never come out of it.

It seems kind of strange to think that you… well… that you do that… so… how do you function?

Well, you know, I was a monk for many years. When I was 14, I left this world for the Middle Ages. It tattooed me for life. I eventually left the Christian Brotherhood, but it had a big impact on me. It taught me how to focus. It taught me how if one wants to do something, one has to forget about oneself and pursue the higher eye within oneself. Our shibboleth was “be in the world, but not of it.” I make do. I’m glad I have the luxury of living in my closet garage here with a 18 foot ceiling. I get to live in my imagination. Of course, the technology trickles down. I’ve had to learn all the nomenclature for filmmaking because I deal with people that are way more talented and more informed than me. I also do use a very high profile of technology for my work. I realize the contradiction of that but I know that in this world if you want to speak to people, I think you have to speak to people through the medium of the day. When in Rome do as the Romans.

Have you heard of E-Sports?

No.

So E-Sports sports are electronic sports. Professional gamers play video games year round and then millions of people watch it. It’s a billion dollar business and you can watch it live from your computer. There are services called “streaming sites” where some of my friends will watch people play video games, and some of these gamers will be making 10 million dollars a year from advertisement revenues.

There’s no end to it. The generations change every couple of years. When I did 4K for visitors, it was on the edge. There was probably one other film done in 4K. Now you can get 4K on your gizmo and it’s 8K, and it’s going to keep going to 16K. Soon we’ll be up to IMAX on 70mm 15 perf. There’s no end because progress has to continue or it falls apart. That’s our dilemma. We live in a world that has a finite capacity and we have an infinite appetite. So we’re headed for trouble.

What are you working on nowadays?

Well, I’m doing a project now called Once Within a Time, and it’s an anarchic comedic fairy tale. You know, I’m an old man busy boy living by my deadline. I’m approaching 80. I’ve wanted to do a comedic piece for children since the 90s, but I didn’t feel mature enough. Now I’ve invited Philip Glass, the composer, and Robert Wilson, the stage director, and together we’re creating a stage play based within a non-literate form. The play centers on the global catastrophe of the environment and children embedded within a destiny which may or may not be overcome. It’s a fairy tale aimed at the heart of the child, a tale of humor where audiences act simultaneously as spectator and participant.

What we want to do is unlike other theatrical pieces. We want it to in tour places where we can reach children who don’t normally have access to theatrical performances because of income. Because there is a huge market now for filmic adaptations of operas and plays, I’m hoping to eventually open it up to that bigger audience. It’s going to take three years to produce, and we’re scheduled to begin this August in Robert Wilson’s Watermill Arts Center if we get the money. So if you put this in your magazine and you raise the money, I’ll give you a good fee.

Maybe I’ll contact the alumni network!

You know, I wrote an article March 19, 2000 for the New York Times. The idea was to conjure an angel for Naqoyqatsi because it had taken nine years to try to get that film going. Lo and behold, off of that article Steven Soderbergh got back to me asking me how he could help.

Changing gears, could you tell me a little bit about monkhood?

I went to school. I did manual labor every day. Everything from working in the fields to working with animals to doing the laundry to preparing food or chopping wood. We did all kinds of prayer services every day. We had liturgy starting at about five thirty in the morning with a bell, and every night ended with the complin, the night prayer. Then there’d be a great silence until after breakfast where you could only speak if you had something useful to say, not just chatter. Let me put it this way: coming from New Orleans La Dolce Vita made the Marine Corps look like the Boy Scouts. It was very intense.

Are you still are you still Christian?

I’m not part of the church anymore, but I do believe in Jesus as a great example. He lived his life for other people and that’s stuck with me. The institutionalization of Jesus is to me a travesty. Anything that has “-anity” or “-ism” at the end of it is something I want nothing to do with.

Why did you leave the church?

I didn’t leave, per se. I had final vows. You had to take temporary vows up until you were 25. Then they’d tell you to go home or allow you to stay. Remarkably, I was allowed to stay, but I was working with street gangs and causing a lot of embarrassment because my work was controversial and got in the press. I was a young zealous monk and had a following of other brothers who wanted to live their vow teaching the poor gratuitously by working with kids who couldn’t afford to go to a school. Anyway, it made things uncomfortable and my superiors asked me to leave the order in 1968. They provided me with the pontifical orders, so the Pope gave me a dispensation of my vows.

What did you do when you left?

The first job I had was as a gravedigger at a Catholic cemetery. Unfortunately, we didn’t have a backhoe, so I’d dig a grave a day and fill up a couple. I worked with two other guys. We got there at six in the morning and left at three thirty in the afternoon exhausted before going to bed at eight. After a couple of months, I left. I said I would rather shovel shit than do this ever again.

How did you get involved in film?

While I was working with street gangs in New Mexico, a brother, Alexis Gonzalez, who was a professor of cinema told me to watch this film by Luis Manuel called “Los Olvidados” or “The Young and the Damned” set in Mexico City at the very end of the 1940s. I saw the film. It was not entertaining at all. It was like a lightning bolt. It was a spiritual experience. I felt that if cinema could have such an impact on me, perhaps cinema could have the same on others. If I’d just spend what time I had left on cinema, I hoped I could perhaps have an impact on people that way.

What is your view of Hollywood?

Many extraordinarily beautiful movies that come out of that business. I’m not trying to denigrate a whole form, but the entertainment industry, the sports industry, the gambling industry, the racecar industry are massive distractions. They keep our attention away from that which is much more vital.

I look at the present as an ancient modernity. I look at the present 2019 as if it were 1896. That’s where my imagination is, and because I see the present from the point of view of the past, I see that this isn’t going to last forever just like 1896 didn’t.

Have psychedelic drugs ever been an influence on your films?

I have done psychedelic drugs, yes. I prefer marijuana to be truthful. Rather than a recreational or medical thing, it’s more of a sacrament to me. It produces what it signifies. But LSD is on a heavier dimension because it can scramble your gray matter around. You can’t take that everyday and stay sane. You can take it occasionally.

I’m sure they’ve been influence. I relate all of the films I’ve made to drugs. Koyaanisqatsi is on speed or coke. Powaqqatsi is definitely hashish. Naqoyqatsi is on LSD. Not that I am promoting those in any way that doing that— I’m just saying that those have been things that are a part of my life and so I have to acknowledge them.

For many students here, the university acts as a pipeline to a great deal of institutional, unfulfilling work in investment banks and industry and government. I wonder what you what advice you have for people like us.

Well gee whiz. I’ve given a few commencement addresses and I think the thing I’ve tried to tell the people that are graduating is that don’t let your diploma be your death certificate. And what I mean by that is that there’s more to life than earning money. Money is important we all need it of course but if it becomes the raison d’etre of living then creativity goes out to do. money can be like a fever. The more you have the more you want.

So, please, I’m not offering this advice to anybody but myself, I decided one day I never wanted to have a job. I decided I’d rather deal with the difficulty of how to stay how to keep things afloat in order to have the opportunity to create with others my own work rather than doing something that was really principally for money.

Did you ever try to become part of the system and make a lot of money?

I didn’t. I can’t tell you why but I think it’s probably my mother’s fault. I was an outcast from the beginning. I had to repeat kindergarten twice because I used to waste time and annoy others. I’d have to pay penance in Catholic School. Every day… Every day. This is not exaggeration. For eight years because of being a behavioral problem. I hated school. It was like being in a prison. Fortunately for me I had a very imaginative childhood with my friends. We lived in tree houses and only went home to sleep and eat. Then leaving home at 14 and joining the Brothers — where it’s about giving rather than receiving — that set me on my path. So as a misfit, I became a deliberate outsider. I live, may I say, very poorly. I feel very bad for my wife but she seems to be okay with it. This is what I want to do. To do films like the ones I make, one has to be willing to spend years living between the cracks.