June was full of reports from officials of the squalid conditions at the border migrant detention camps. Tweets from Members of Congress detailing warehouses full of lice-riddled and unwashed children roused national outcry. Within the month, Congress approved a multi-billion-dollar stimulus package aimed at moving the overcrowded children into an appropriate facility. Upon the bipartisan passage of this emergency humanitarian aid, once fever-pitched calls for action grew quieter in the national conversation. But the crisis persists – 52,000 immigrants remain confined in detention facilities.

In the past month, reports alleging medical maltreatment at ICE facilities and news of a surge of Mexican migrants have appeared alongside the Trump administration’s unveiling of a new regulation that would allow for the indefinite detention of migrant families. With the nation’s worry and outrage prematurely assuaged by June’s humanitarian aid package, these stories have been largely relegated to second-page status. And while the drift in national attention is understandable in our time of endless breaking news, this issue remains dire and demands another wave of attention – one that would result in lasting solutions at the federal level. Something must be done to reignite the compassion felt in June, and one thing is clear: the American public will not be inspired to address the border crisis through more statistics and pixelated images of overcrowding. Journalists, keenly aware of this, have been fighting access restrictions to the detention centers – seeking greater transparency and a way to personalize the story.

A few years ago, it was neither the lengthy war nor the staggering death toll that woke the world up to the Syrian refugee crisis – it was three-year-old Aylan Kurdi lying washed up and still on a Turkish beach, photographed by Nilufer Demir. The image electrified the international community, and within a week of its widespread publication, Syrians were greeted warmly at newly opened European borders. Studies conducted around this event have revealed the impotency of statistics in inciting empathy and the human psychological tendency to be moved to action through an image of a suffering individual. At the time of Aylan’s photo, the Syrian Observatory for Human Rights had been reporting a death toll in the hundreds of thousands, but the governmental and civilian response was meager. Only with the image of a single boy did the world begin to pay attention. The independent photojournalists who have deemed the Trump Administration’s denial of access to the detention centers unconscionable are acutely aware of this behavior. Calls for increased access are likely twofold: to monitor the situation, and to take a heart-wrenching photograph with the power to launch the issue back into the forefront of national news.

The phenomenon of a single image of a suffering individual stirring the world to action is called the “iconic victim effect” – and it is powerful. Tracking data trends of Google searches and Red Cross donations before and after the release of Demir’s photograph, psychological researchers were able to determine that the photograph had a dramatic effect on the international community. The week following the publication of the image saw a 100-fold increase in daily donations to Syrian refugees, and the daily searches for the terms “Aylan,” “Syria,” and “refugee” soared. It was roughly six weeks before either metric returned to the levels exhibited prior to the picture. And though the initial deluge of donations and searches was impermanent, the picture also generated many repeat contributors, who continued their monthly donations long after the photograph’s publication.

With evidence of the efficacy of the “iconic victim effect” in inciting compassion so apparent, it is tempting to call for a picture of a figurehead victim to personalize the border crisis. At the migration detention camps, Border Patrol agents, under the guise of protecting the identity and privacy of individuals in custody, have forbidden visitors from taking such photographs. Congress members’ cell phones were confiscated during their visit, and even the Office of the Inspector General’s documentation of the overcrowding hid the faces of the detainees. The exclusion of photographic press coverage, which could potentially reignite the compassion and attention felt in June, has been decried as another instance of Border Patrol non-transparency. With increased journalistic access, it is thought, pictures of individuals in the detention facilities might generate the necessary public attention. However, such a push for an “iconic victim” – a tokenization of suffering – is riddled with ethical concerns. The welfare and personhood of the individual serving as the “iconic victim” cannot be forgotten.

In June of 1985, the searing green eyes of then-unnamed ‘Afghan Girl’ appeared on the cover of National Geographic, making thesince-identified Sharbat Gula the poster child for Afghanis fleeing to Pakistan. It was seventeen years before the public would learn her name, and in that time, she had never seen her own portrait that haunted millions worldwide. Since identification, the picture, which made her the “Afghan Mona Lisa”, compelled the Afghani government to provide her with a home and medical care upon repatriation. However, the image, and her status of “iconic victim,” also endangers Gula; her new home came highly secured for fear of conservative Afghanis who take issue with women appearing in the media.

Gula is not the only “iconic victim” bereft of a pleasant, storybook-ending. In the case of the ‘Napalm Girl’ Phan Thi Kim Phúc – the 9-year-old whose image would convey the horrors of the Vietnam War – the infamous image proved inescapable. Nick Ut’s image of Phúc running naked and screaming from pain after a napalm attack led to her transfer to a facility equipped to handle her severe burns, but, years later, the image would also consign Phúc to be a propaganda tool for a new communist government. Now valuable evidence of the Western world’s brutality, Phúc was carefully monitored, forced to quit school, and instructed to speak scripted words to journalists. The image, and her status as iconic victim, proved an enduring burden.

We cannot, in our effort to trigger public outcry, create such casualties of “iconic victims.” The stories of Sharbat Gula and Phan Thi Kim Phúc show that to be the face of a tragedy is potentially devastating. It is true that something must be done to rouse the American public to action with regard to the dangers of migrant detention facilities. And psychological studies demonstrate that a single face of crisis elicits empathy and compassion in a way that statistics, no matter how alarming, cannot. But we must be wary of calls for greater transparency, as we now know that with photographic access can come lasting unintended consequences. Rather than creating unwitting tokens of tragedy through these iconic photographs, journalists should look for alternative ways to personalize mass crises.

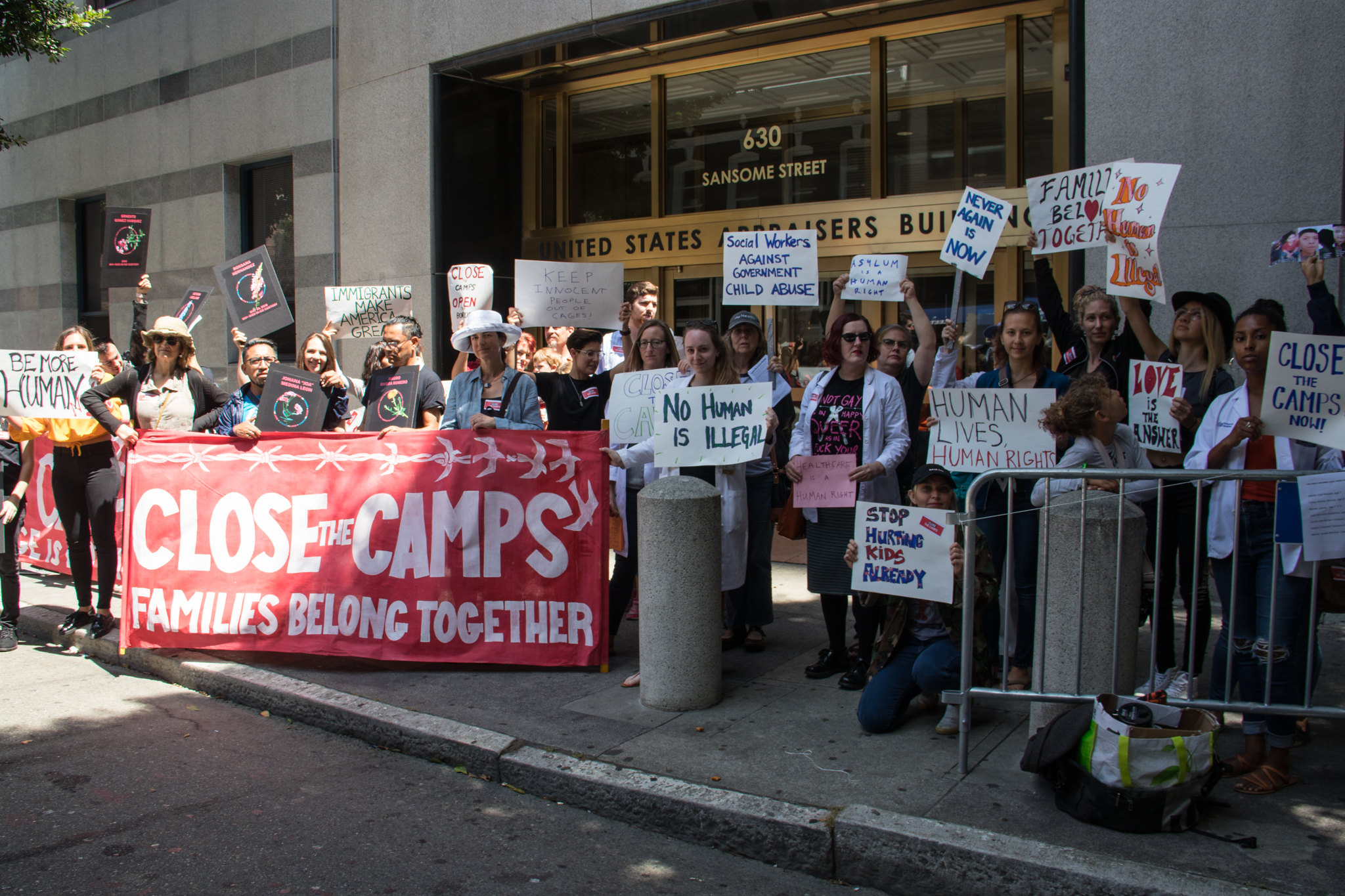

Photo: Image via Peg Hunter (Flickr)