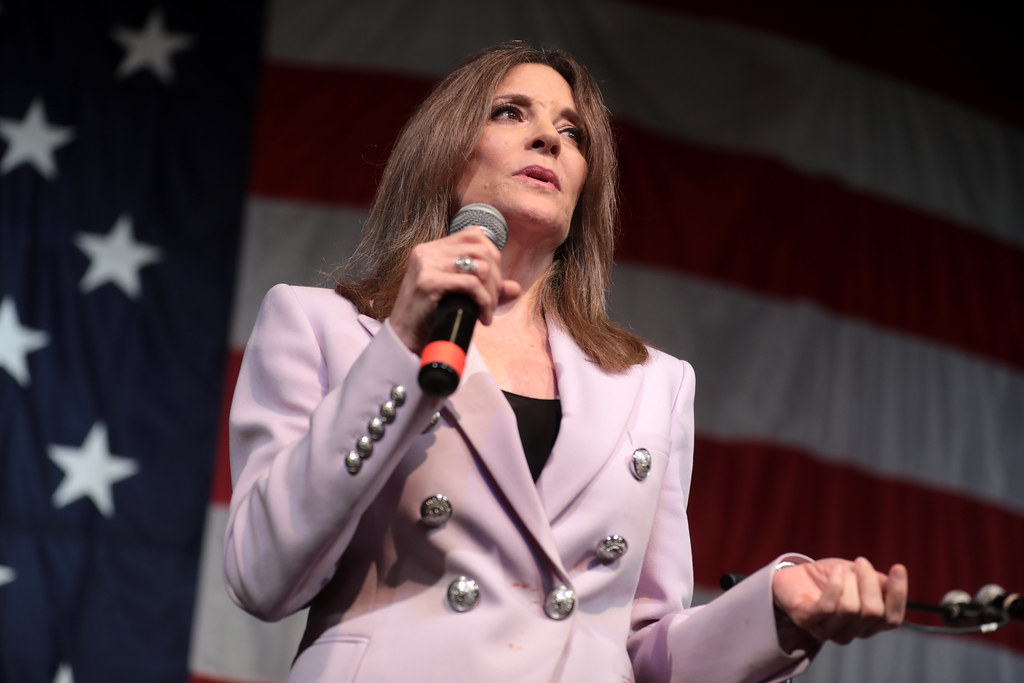

Marianne Williamson is a bestselling author, activist, spiritual leader, and a candidate for the 2020 Democratic Nomination.

Nick: I’m very interested in how you think about politics. You’ve spoken about spiritual problems facing the country. How can we tell the difference between a problem which is material in nature, like that people just need some more money or a better job, and a problem which is spiritual in nature?

Marianne: A problem on the level of external need is the level of symptom, but for every symptom, there’s a cause, and that’s where spirituality comes in. Spirituality is simply the path of the heart. Some policies have heart and some policies are heartless.

To say, for instance, that we will base our educational funding primarily on property taxes is to say that if a child grows up in a wealthy neighborhood, that then the child will have a very good chance of high-quality public school education. But, if a child has the misfortune to grow up in a neighborhood that is less financially well advantaged, then there’s a high probability that the child will not experience a high-quality public school education. That child might go to a classroom where they don’t even have glue sticks and paper, where they don’t have the adequate school supplies with which to teach a child to read. If a child cannot learn to read by the age of eight, their chances of high school graduation are drastically decreased and their chances of incarceration are drastically increased.

Now at the level of the symptom, obviously the material issue is that not all of America’s children are being properly educated. But, on the level of the cause, the issue that should be addressed is the fact that we base our educational funding in such a way. And that’s the heartlessness — the basic heartlessness — and lack of deep human value in allowing your public policy to be driven by an amoral economic system, one that places short term profitability for huge corporations before the need of the child to be educated or to be fed. Not to mention the need of millions and millions and millions of people to have the basic chance to thrive.

Nick: Do you think all political problems are, on some levels, spiritual problems manifesting themselves in our politics?

Marianne: Spirituality is just a word. There’s no reason for any of us to get too caught up in words, but I think that our politics is our collective behavior and that our collective behavior is not fundamentally different than our individual behavior. Everything we do reflects something that we think. Sometimes our thoughts are open-hearted, generous, kind, compassionate, and selfless. Sometimes our thoughts are mean-spirited, judgmental, and limited.

Our collective behavior is no different than our individual behavior. You stand on a certain ground within yourself with everything that you do in life. Whatever you do will have consequences. That is as true of a nation as it is of an individual. If you’re coming from a more open-hearted place, your life is going to work better. You will attract greater good. You will build deeper relationships. You will help foster conditions within whatever system you are a part of to promote greater peace, harmony, creativity, and productivity. On the other hand, if you bring negative energy into any system in that you’re not kind, people don’t like working with you, then you’re not going to attract as great a good. There will be greater limitations rather than limitless possibilities. All that politics is is those same principles played out on a collective level.

Nick: When we talk about improving people’s wellbeing, spiritually or otherwise, it seems that part of the project must be personal. It is something that one undertakes for oneself. But, politics has a role as well. So, where do you see the role of politics and where do you see the role of a person’s own choices in creating these improvements?

Marianne: There are high-minded conservative principles and there are high-minded liberal principles. President Eisenhower said, “The American mind at its best is both things.” The high minded conservative principle has to do with personal accountability and the high-minded liberal principle has to do with how systems themselves should be just. So obviously people need to take personal responsibility for their own wellbeing. On the other hand, it’s a whole lot easier to do that when your water is not contaminated and there aren’t so many carcinogens in your food and there aren’t so many toxins in your air and it’s not so hard to get a decent education and so forth.

Public policy is not responsible for an individual’s choices. Although, when it comes to children, there is an extent to which I believe that society is responsible. Society is at its best as a constant interplay, a kind of yin and yang, between the private and the public spheres. Both are important. So while we’re responsible for our own choices, as citizens, I think we should think of ourselves as the immune system of the body politic.

As citizens, we’re also responsible for our public choices. That’s why chronic political disengagement on the part of so many is so dangerous for our democracy.

Nick: So then, is a politics of love about creating the sorts of environments in which humans can flourish?

Marianne: I think the politics of love is the politicization of the best of who we are, the angels of our better nature.

We know what a politics of fear is. It’s where you take racism and bigotry, antisemitism, homophobia, white nationalism and turn them into a political force. Nobody doubts the power of fear when it is politicized. We have seen it throughout history, what collective hatred can do. But we’ve also seen what collective love can do. It’s what Gandhi used in the Indian independence movement was. It’s what Martin Luther King used in the civil rights movement in the American South during the 1960s.

This is not a new idea, that people can bring into a collective field of possibility the best of who they are.

If you politicize the idea that our children should be fed, that there should not be 13 million children hungry in the United States of America, that there should not be 100,000 homeless children, that there should not be half a million homeless people in the richest country in the world, period, that is a politics of love.

These kinds of problems — they are not just hard data — These are people’s lives.

We’re talking about 41 million people in America living in poverty, and another 93 million near poverty. Those are people who live with chronic economic anxiety every day of their lives, wondering what would happen if they got sick, wondering how they will possibly send their children to college. That’s a lot of human despair, the conditions of which are fostered by an amoral economic system that has developed over the last 40 years.

We’ve had a massive transfer of wealth into the hands of 1% of our population such that they now own more than the bottom 90% and that economic squeeze has created so much human despair that societal dysfunction is almost inevitable.

What does a politics of love do? A politics of love knows that you need to shift your bottom line from an economic to a humanitarian one. When we do that, this will not only improve the state of our humanity, but it will improve the state of our economy as well, because there is nothing stable nor sustainable either in economic terms or in democratic terms in a situation where such a large amount of wealth is concentrated in the hands of so few.

Nick: Do you see yourself as advocating for a new kind of capitalism or something different entirely?

Marianne: I am not an anti-capitalist. I want to see capitalism with a conscience. The free market has been good to me. I’m an author; I’ve had bestsellers. The problem is not that some people can create wealth in America. The problem is that today, not enough people have a reasonable shot at creating wealth in America. I do not believe that the average American who makes money in America wants to feel that they are doing so at the expense of other people having a chance. You know, we’re living in a very pregnant moment. We have very powerful capitalists’ voices such as Ray Dalio, Jeremy Grantham speaking out about this. Even the Business Roundtable made a statement that short-term profit maximization should no longer be the goal of the US corporation.

Nick: You’ve talked about the history of spirituality in politics, from the Founding to the ideas of leaders like Martin Luther King. Do you see your campaign as returning the United States back to a historic track that we’ve lost in the last 40 years? Or, do you see yourself as aiming for new, systemic changes?

Marianne: Our historic track is one of systemic changes. What we have always been from the very beginning is both. Go back to the signing of the Declaration of Independence. You see that 56 men risked their lives to sign a document that established the most aspirational and enlightened principles that ever formed the core of a nation. And, 41 of them were slave owners. So, we’ve always been both. We have always been founded on the ideal of that perfect union, the ideal of equality and liberty and justice for all, the ideal that all that God gave all men inalienable rights to pursue happiness. And, there had been in every generation those who were willing to struggle and sacrifice for those ideals. But we’ve also had in every generation, including our own, those whose main economic interests were completely opposite of those ideas. Now, what’s interesting in American history is to see the narrative over time, because we did answer slavery with abolition.

We answered the suppression of women, with the women’s suffragette movement and two major waves of feminism. We answered institutionalized white supremacy and segregation with the civil rights movement. The way I see this movement is simply the latest iteration of that historical drama and dichotomy, that bipolar nature of our national DNA. So we’re simply facing, once again, that struggle, that contest between what is essentially a democratic ideal and what is essentially an aristocratic ideal. We have reverted to corporate aristocracy. We’ve repudiated aristocracy in 1776 and it is time to repudiate it again.

We need to repudiate aristocracy in order to reclaim our moral compass because aristocracy has no moral compass. It’s all about sucking up resources to a small group of elite. And I see my campaign as simply part of a historical narrative that has compelled every generation and will compel generations after us. Something happens in the heart when we rise up and recognize what’s going on and when what’s going on is wrong, do what we can to change it.

Nick: You’re clearly very well studied in American history. Has this been a lifelong interest for you? What role does your knowledge of history play in your political thinking?

Marianne: It plays a tremendous role. You go to therapy or you go to a support group or you read up on your family’s history because the more you know about what came before you, the more empowered you are trying to discern your place in that history. You come to understand what your parents did right and what your parents did wrong. You understand the things you want to continue and extend, the places where you want to stand on the shoulders of the giants before you. But, you also come at a certain point to understand where your parents had it wrong. The patterns were neurotic. They were not healthy. And those, you seek to analyze in order to change them so that they will not have an effect on your life in the future until that you won’t carry them on and give them to your own children

We need to do that as Americans as well. We need to be clear about our history to see where America has gotten it right, where America gets it right and where we want to do it even better. And we also want to know the things that the United States has done that were wrong and is doing that are wrong so that we can be agents of change. Now in the late nineties, the third book I wrote was called Healing the Soul of America. I studied American history quite deeply. I’d always had an interest in it, but not that much more than a passing interest. Then I wanted to write a book about American history, about spiritual principles. Because, what I’ve seen in life is that the psychological and emotional dynamics that prevail within the life of one person prevail within a system as well.

All that a country is, is a group of people. So in the 90s, I started doing a deep study of American history, which yes, very definitely, has impacted my thinking. So many of the things I’m talking about now, whether it has to do with racial inequality, corporatocracy, wealth inequality, mass incarceration, reparations for slavery, those things I was talking about back in the 1990s. So many of the things that are what you might think of a stage four cancers today, they were stage one cancers back then. People back in the 90s were talking about how wonderful everything was, and I was going around saying, “Well, doesn’t that depends on what neighborhood you live in? Doesn’t that depend on what part of the world you’re living in? Everything that has blown up in our face and become such dramatic stresses and challenges now, they were already there in their initial phases. They just weren’t obvious to the non-observant eye.

Nick: Do you see the spirit of America as the tension between our ideals and our history, and our project to rectify that tension?

Marianne: Absolutely.

Nick: The New York Times recently reported on the “Ok Boomer” joke as evidencing this tension between older generations and younger generations, with young people making fun of the “Baby-boomer” generation. What do you think of these conflicts?

Marianne: I think the older you are, the more you know certain things and I think the younger you are, the more you know about certain other things. The younger you are, the more you know what’s going on right now, but the older you are, if you’ve learned from your experience, the deeper insight you have into the cycles and the patterns of life, especially those things which do not change. The younger you are, you tend to have much greater insight into what changing you older you are. The more insight you have into the things that do not change. And I think both are extremely important. The sharing of information and insight between the two is an engine of greater peace and prosperity for both.

Nick: How can we understand each other better, given these different perspectives?

Marianne: Well, I think that the problems we have in our political discussions are broader and more expansive than just that. Wherever there’s a lack of deep listening, wherever there’s judgments, wherever there’s lack of compassion, we don’t hear each other. So, whether the person your who’s, whose truth you’re obstructing is 16 or 66 you’re losing out. No one has a monopoly on truth and everybody has a piece of the mosaic that we all need right now, which is the particular insight that comes with their particular life experience and nobody’s life experience is more important than anybody else’s life experience. That’s the whole ideal of American equality right there: The equality of what you have to give. It’s not just the equality of your creation, but the equality of your gift. And our public dialogue, the space of political dialogue, has been so desecrated to the point where we not only judge another person’s opinion, we try to shut them up and stop them from even expressing it. A smug, self-righteous, and intolerant left winger is no less dangerous to the social fabric of our country than is a smug, self-righteous, intolerant right winger.

We need a political revolution in the United States, but it needs to be a peaceful revolution, a nonviolent revolution. JFK said that “those who make peaceful revolution impossible make violent revolution inevitable.” These are revolutionary times, but the Gandhian principle of nonviolence that was then adopted by Martin Luther King and brought over to the United States for application to the civil rights movement posits that harmlessness must first begin in our hearts, that self purification — that’s a basic core principle of the philosophy of nonviolence — preceed direct political action. So whether you’re an older person tempted to judge a younger person, or you’re a younger person, tempted to judge an older person, by definition, you’re wrong.

Nick: Beyond not starting needless wars and not committing needless violence abroad, what does a politics of love look like in its foreign policy?

Marianne: I want to establish a United States Department of Peace and I want a Peace Academy as well as a military Academy. Right now, we spend $760 billion a year on our military, and that is hundreds and billions over and above what the military says that they need. Meanwhile, our budget is 40 billion for the state department, which does diplomacy development, and mediation. Of that 40 billion, 17 billion goes to the USAID, which is longterm development and humanitarian assistance. And then next to that, also within the 40 billion, less than 1 billion that goes to the peacebuilding agencies. What we need is the equivalent of the health and wellness space within the body of Politics. You don’t just take medicine, you also have to cultivate your health. We can’t just endlessly prepare for war. We need to wage peace.

I look at the military like I look at a surgeon. Does the United States need to have the best surgeon on hand? Absolutely, we do. But no one in their right mind has surgery if they don’t need it. Peacebuilding skills are just as specific, they take just as much sophisticated expertise, and in some cases around the world, just as much courage, by the way, as do military skills.

They have to do mainly with these four factors: Expanding educational opportunities for children, expanding economic opportunities for women, reducing violence against women, and ameliorating unnecessary human suffering wherever possible. Statistically, when those factors are present, the incidence of peace is increased and the incidence of conflict is decreased. So, we should see large groups of desperate people as a national security risk, because anytime there are large groups of desperate people, you have that Petri dish that we were talking about before, out of which societal dysfunction is almost inevitable. Desperate people do desperate things. Desperate people are more vulnerable to ideological capture by genuinely psychotic forces. So, to me, a Department of Peace will have an international element as well as a domestic element as we make sure that in order to increase peace, all of public policy is based around the core principle of helping people thrive.

Nick: You mentioned human rights issues: When should we think about using military intervention to protect human rights if diplomacy doesn’t work?

Marianne: I think there are three main categories that present the possibility for the legitimate use of military force. First, if the Homeland itself is threatened. Secondly, if the Homeland of an ally is threatened. Third, if the world order is threatened.

Nick: I want to ask you a few questions about the campaign itself. It seems to many watching that there have been ways in which you’ve been treated unfairly, both by the Democratic Party establishment and by the Media. Do you think that’s true and have you been surprised by that?

Marianne: Yes, it’s true. Yes, I was shocked, but I suppose not surprised. Maybe I was surprised by the merciless quality of it. At the same time, I’m not a victim. I didn’t think this was going to be a walk in the park. And I am gratified that so many people have seen it for what it is.

Nick: How have your views the Party, as an institution, changed since entering the race?

Marianne: What I have seen is that the system is even more corrupt than I feared and that the people of the United States are even more wonderful than I knew.

Nick: Do you think that some people are scared of using spiritual language in politics?

Marianne: I think that what I bring to the table is clearly disruptive and inconvenient to the establishment, but my spiritual language is the least of it. I’m talking about something much more than language here. I’m talking about a fundamental pattern, disruption, of the economic, social, and political status quo. That’s what they find inconvenient. Let’s be clear: They’re not scared by words. They’re scared of my policy ideas. I want to see a virulent strain of capitalism no longer corrupting the US government. I want to see economic justice in this country. I want to see a Department of Children and Youth. I want to see alleviating unnecessary human suffering as a priority. I want to see reparations paid for slavery so that we can end a chapter of our history and begin a new one. I want to see reparative measures in the direction of Native Americans. And, I want to see an overturning of the dominance of the military-industrial complex in our national security agenda. I want to end the corporate aristocracy, by which health insurance companies and big pharmaceutical companies, and gun manufacturers and chemical companies and food companies in oil and gas companies and defense contractors get their short term profits met first. And then whatever crumbs having to happen to be left on their table, I suppose to drop down in the form of job creation, to the, to the near-serfs who are American citizens below. We’re not supposed to do that in America and I’m calling it, I’m naming it. Of course, there are those who don’t like that.

When people like that are speaking out, you know that there are changes in the air. I think there’s changes in the air for a reason. Part of it is true wisdom and nobility. That’s important, because not every rich person in America is a greedy bastard anymore than every poor person is noble and pure. No socioeconomic group has a monopoly on conscious. I’m talking to the American in people and there are many billionaires and people of vast wealth who agree with everything that I’ve been talking about with you here today. This is not about rich versus poor. This is about democracy versus corporatocracy. Louis Brandeis, the late Supreme court justice said, “We may have democracy, or we may have wealth concentrated in the hands of a few, but we can’t have both.”

I’m not romanticizing or whitewashing American capitalism before the 80s, but I am saying that a definite break occurred in the 80s whereby, with the amoral philosophy of trickle-down economics, the United States bought into this notion that short term-profit and the fiduciary responsibility to the stockholder without any comments and sense of ethical and moral responsibility to workers, to community, to environment with any, with and without and with as little government regulation as possible, has created a disaster. It has created a catastrophe in the lives of millions of people. And, it’s time to recognize what a moral failure it has been and to recognize what an economic failure it has been as well. It has destroyed on middle class. It has created the greatest wealth inequality since 1929. And we need more than incremental change. We need to recognize that this pattern must be interrupted. That virulence strain of capitalism, we need to see its demise. I don’t believe that it will destroy capitalism at all. I feel the way Franklin Roosevelt felt. He said, “I’m not, I’m not destroying capitalism. I’m saving capitalism.” It will save capitalism, not destroy capitalism, for capitalism to reclaim a moral center. I believe in capitalism with a conscience.

Nick: What do you think went wrong in Hillary Clinton’s campaign?

Marianne: Well, obviously the 2016 election was a bit of a perfect storm, but I do believe that one big mistake she made was talking about Donald Trump too much. I also believe that there was a very legitimate rage felt by millions and millions and millions of people in America who believed — rightfully so — that the system was rigged against them, in all the ways that I’ve been saying. Only two candidates named that rage, validated that rage. They were Bernie Sanders and Donald Trump. I felt that that rage was going to express itself in a populous cry of despair. It was either going to be in a progressive populism such as Bernie or an authoritarian populism such as Trump. Hilary’s mistake, in my opinion, was that she did not name the rage. She was talking about how we needed to continue with all this success of the eight years previous while millions of people were thinking, “Success? Are you kidding me lady? I’m drowning here?” I had great concern at the time and unfortunately my concern turned out to be justified.

Nick: If I could just ask you two final questions: First if you could convince your fellow primary candidates of something to think more about or to understand, what would that be?

Marianne: I wouldn’t be so presumptuous as to say what other people should understand or focus on. I believe that all of us are focused on the ultimate goal here. I think that all of the candidates are deeply aware of the dangers that confront us. I can’t imagine anyone running for president who takes this on without a deep and passionate conviction that the job needs to be done. And, that we’re the one who can do it. I think we all share a deep concern that if you think things are bad now, just give this man another term. I think that realization is visceral within all of the candidates and that’s what’s most important.

Nick: My final question, you tweeted yesterday that, “the ultimate purpose of all human endeavor is to reduce suffering and uplift the human condition. That is true in our political as well as our personal behavior.” I’m wondering in terms of our personal endeavors, how do you think we, as citizens, can be better at uplifting others?

Marianne: Every cell is guided by natural intelligence. Some cells are guided to the pancreas; some cells are guided to the heart; some cells are guided to the blood; some cells are guided to the lungs. Every once in a while, a cell loses its natural intelligence and goes off to do its own thing. The cell is no longer interested in serving the healthy functioning of the pancreas. It’s no longer interested in serving the healthy functioning of the lungs. That’s a malignancy in the body and that’s also a malignancy in civilization. That is what has gone wrong with our world. We had been human consciousness that’s been infected by the malignant thought that “It’s all about me.” As we return to the native and natural intelligence within ourselves, then just like the cell in the body, we are guided to where we can best serve. That’s the purpose of religion, spirituality, psychotherapy, reflection, yoga, any kind of internal work where you’re trying to mine the gold of your own internal wisdom. I believe we all have a compass, and the task in life is to align ourselves with that compass. It’s a combination of finding that which truly brings us joy and ways in which what we love to do can be of greatest use and service in the world.