“It started out as a kiss; how did it end up like this?” wonder The Killers in their timeless 2003 hit “Mr. Brightside.” This refrain doubles as a genuine question about Jordan, where, this past summer, a single kiss propelled the desert kingdom into mayhem.

In June, Netflix released its first Arabic-language original series, Jinn. The show was intended to remedy gross misrepresentations of the Arab world, but it instead sparked uproar in Jordan, where it is set. The cause of this rage? In one episode, high school students are seen kissing at an Amman party featuring substances considered haram (forbidden) in Islam. Public outrage over this scene swiftly spilled from the YouTube comments section into the Jordanian Parliament, where government officials convened an emergency meeting to discuss the show and its allegedly sullying effect on Jordan’s global image. The Kingdom’s Attorney General then launched an official investigation into Jinn, referring the series to its cyber-crimes unit and threatening Netflix with vague “punishment.”

Since then, the Jordanian government has lapsed into silence on the matter. Meanwhile, Jinn remains readily available to stream on Netflix. Either Parliament’s fury-fueled actions were embarrassingly toothless, or they were a performative ploy to appease public opinion. Given that Jordan typically has no problem censoring media at every turn, the former case seems far more probable. In short: King Abdullah II doesn’t know how to deal with Netflix, nor does it seem that he’ll get a grasp on the platform anytime soon.

Netflix is only widening its cultural influence; by August, the media conglomerate had already released its second Arabic-language original, Dollar, and plans for more series are in the works. Not only do these shows reject traditionally skewed and war-ridden depictions of life in the Middle East, the global ubiquity of multinational streaming platforms like Netflix also offers a unique opportunity to promote cultural freedom and challenge seemingly rigid censorship laws in the Arab world.

The rise of unrestricted access to international media certainly challenges Jordan’s cultural and political uniformity. Though euphemistically dubbed a “parliamentary constitutional monarchy,” Jordan’s government possesses all the trappings of an autocracy. King Abdullah II appoints the Prime Minister and must personally approve all pieces of legislation, rendering the Jordanian Parliament a de facto formality.

It should come as no surprise, then, that censorship in Jordan is quite draconian. The task falls to the Jordanian Media Commission (MC), which features both “press and publications” and “audio-visual” branches, as well as accompanying codes of conduct and enforcement mechanisms. Sex, politics, and religion form an un-holy trinity of Jordanian censorship; the MC bans all media that even remotely touches upon any of these topics. Although Jordan’s intensely conservative culture partly accounts for this moratorium, much more than cultural preservation is at stake. Rather, the entire legitimacy of Hashemite rule rests on its religious claim to authority, which in turn stands on the delicate intersection of these three topics.

Like many rulers in the Middle East, the Hashemites were installed by the British to govern Transjordan in the aftermath of World War I. They led the Arab Revolt of 1916, during which they gained trust by claiming to be the direct descendants of the Prophet Muhammad, a purported connection that the Royal Hashemite Court (RHC) vigorously defends to this day. Undisguised insinuations that the Jordanian government is the modern extension of the Islamic caliphates in turn serve to justify its overtly nepotistic, monarchical character. To challenge the Hashemites’ control of the trinity is to call into question Jordan’s entire reason for existence.

Understandably, then, the MC takes its job extremely seriously. Censors have doctored everything from Fast and Furious 7 (which mentions a wealthy Jordanian prince) to The Wolf of Wall Street, which becomes a whole half-hour shorter when watched in Amman and stripped of all sex scenes. Bands like Mashrou’ Leila are prohibited from performing because they have openly-gay members, and any media mentioning Saddam Hussein, an absolute superstar in Jordan, is promptly banned, lest his reputation risk posthumous degradation.

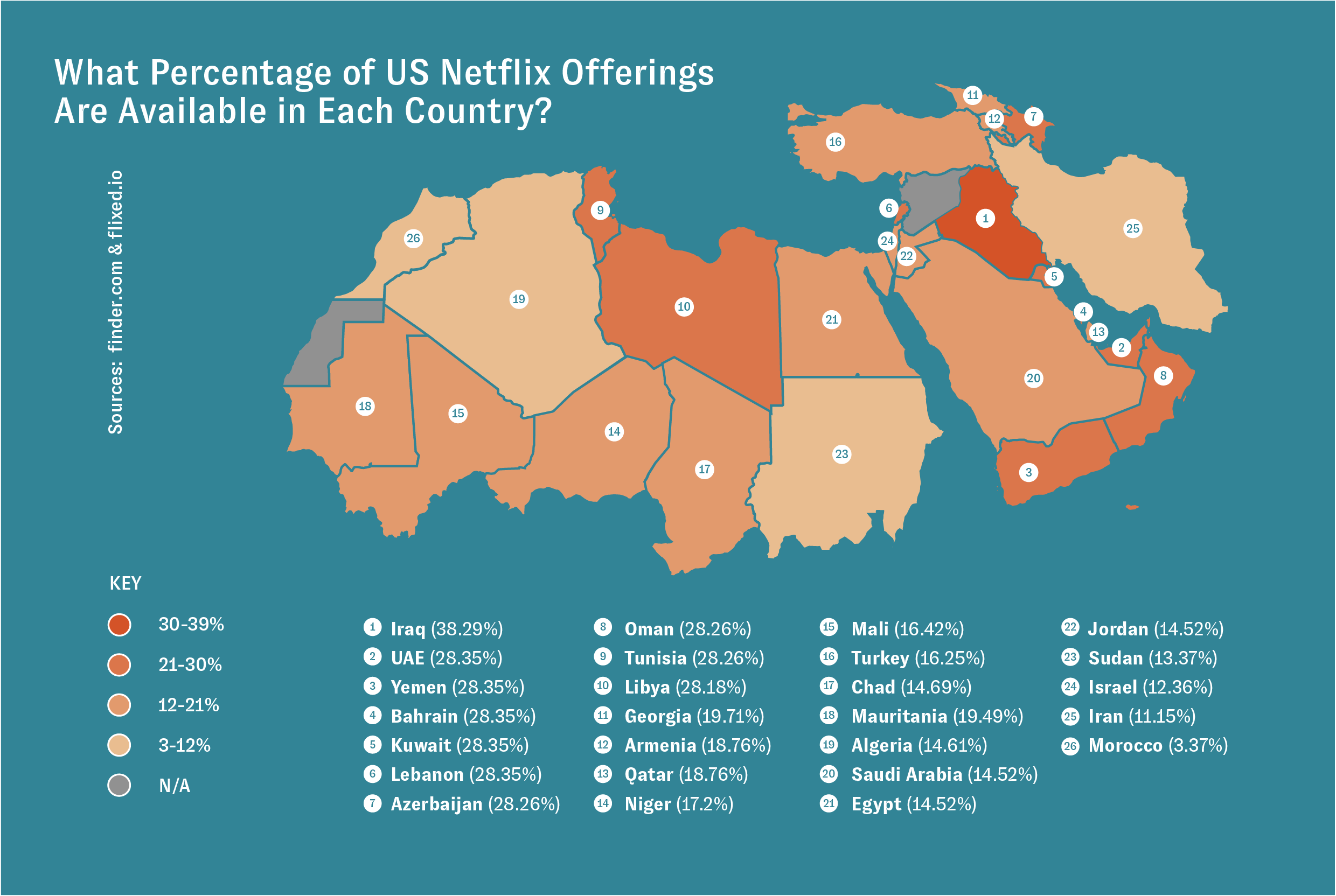

Enter streaming, which has transformed the internet into a cultural minefield. One can listen to Mashrou’ Leila on Jordanian Spotify before indulging in an hour of entertainment on Netflix, where shows like Sex Education are readily available on Jordanian WiFi. Boasting 140 million subscribers worldwide, Netflix perhaps best exemplifies the globalizing power of streaming. The platform is available in 190 countries, notably absent only in China, Syria, and occupied Crimea.

Legally, Netflix occupies a nebulous space, as it is uncertain who governs the internet powerhouse. Importantly, a distinction can be made between Netflix’s original shows (Orange is the New Black) and those to which it buys rights (The Office). Barring its infamous capitulation to Saudi Arabia regarding one episode of Hasan Minhaj’s Patriot Act, Netflix generally makes its original series available everywhere it operates, while non-originals may be viewed only in select locations. By allowing individuals to easily consume shows outside their own regulatory spheres, original series partly erode the supervisory capacity of autocratic states like Jordan.

Jinn serves as Jordan’s first real foray into the mess that is internet streaming. Though the MC is charged with censoring media, it does not grant permits for media production. These are distributed by the Royal Film Commission (RFC), which eagerly awarded Netflix authorization to shoot Jinn in 2018. At the time, the RFC had been excited about the potential tourist revenue a show based in Jordan and starring Jordanians might accrue. Backlash against Jinn prompted the RFC to make a public concession that the Netflix deal had been an error and claim to have been deceived by what it saw as a great opportunity.

In a statement, the commission underscored that Netflix is a private platform only accessible to those with subscriptions. The MC followed up by confining its audiovisual censorship mandate to publicly available content and theatrical productions, deliberately exempting streaming platforms. Such evasive maneuvering signals that the Jordanian government has effectively given in.

By implicitly admitting defeat, Jordan has acknowledged something crucial: Streaming won’t be brought down, at least not anytime soon. Yes, autocrats continue to plot the demise of Netflix: In August, Turkey began to force platforms to share consumer data and receive official government licensing in order to operate. But the rate at which ideas and content travel on the internet outpaces sluggish bureaucracy by a ratio of milliseconds to months. Moreover, platforms like Netflix have become so cross-cutting in their audience and so central to daily life that they will not disappear. Nor will regulation anger only fringe groups; on the contrary, targeting the streaming industry is sure to trigger a movement that unites even the most disparate demographics.

For the time being, we exist in a precarious void of opportunity: The means of dissemination are there, and the obstacles are only in the early stages of conception. So let’s take advantage of it.

Infographic by Minji Koo ’20, data by Erika Bussman ’22