The so-called “gig” economy is, for lack of a better word, gig-antic. This market, characterized by its dependence upon freelance workers and independent contractors, accounted for 94 percent of net employment growth in the U.S. between 2005 and 2015. Indeed, it’s quickly become the go-to for those in search of a new job; now, individuals can babysit, drive Ubers, cater a dinner party, write code, and land a “penetration testing job”—all in the gig economy (the last one isn’t what you think).

Though the gig economy is radically transforming the fundamental relationship between labor and capital—and allows millions of millennials to Postmate their oat milk in record time—it also poses an existential threat to the modern welfare state. Left unchecked, it entrenches workers’ dependency on a shrinking social safety net and threatens social and economic mobility.

Interestingly, the American workforce didn’t always look like this. Prior to the 1970s, employees and their employers entered informal but trusted social contracts with one another. Wages rose in tandem with productivity. Meanwhile, health care, steady hours, union benefits, retirement contributions, and the ability to work toward promotions within one’s firm made upward mobility a real possibility for workers. Ultimately, the safety net provided by this structure of employment left parents confident that their kids would end up better off than they were.

Soon after, however, this shot at upward mobility grew elusive. 90 percent of Americans born in 1940 saw better economic conditions than their parents, yet for those born in 1980, this dropped to just 50 percent.

So what changed? Since the late 1970s, financial liberalization and global market integration have enabled companies and industries to substitute stable, long-term, and benefit carrying jobs with more flexible and precarious forms of employment. This process—dubbed the “fissurization” of the American economy by economist David Weil—has led companies to construct vast subcontracting networks, outsourcing operations once central to their business practices to cheaper and less regulated third-party suppliers. The gig economy is the apogee of our fissured workforce.

Admittedly, this new market structure does have certain conveniences. Gig employers tout the freedom and autonomy enjoyed by their workers, often citing the flexibility that comes with “being your own boss.” Gig work has also lowered barriers to market entry, a phenomenon best illustrated by Uber’s disruption of the taxi cartel. Drivers once had to navigate a complex certification process in order to acquire a taxi medallion. Now, it takes just a few days to register as an Uber driver, demonstrating that gig networks often provide an avenue through which otherwise excluded individuals can earn a wage.

But flexibility comes at a price. Market exclusion and unemployment are issues that merit serious attention, but gig jobs fail to provide a sustainable and robust solution. Uber, for instance, legally classifies its drivers as independent contractors, not employees. By making this distinction, the company exempts itself from worker’s compensation laws, meaning it doesn’t have to pay for most benefits, payroll taxes, or overtime fees. These companies treat their workers as side-hustlers, but many workers depend upon such gig work as an essential source of income to make ends meet. Characterizing gig work as merely a side-hustle ignores the reality of a deeply flawed system—one that compels individuals to work overtime just to earn a living.

Another shortcoming of the gig structure is that it often prevents workers from unionizing or collectively bargaining for better working conditions. Antitrust law, originally intended to block concentrations of market power, is now used by corporate lawyers to prevent independent contractors from forming unions on the basis that such activity is price collusion. Indeed, corporate efforts to undermine unions have turned militaristic: In 2012, Walmart went so far as to hire Lockheed Martin, a defense contractor, to weed out union activity.

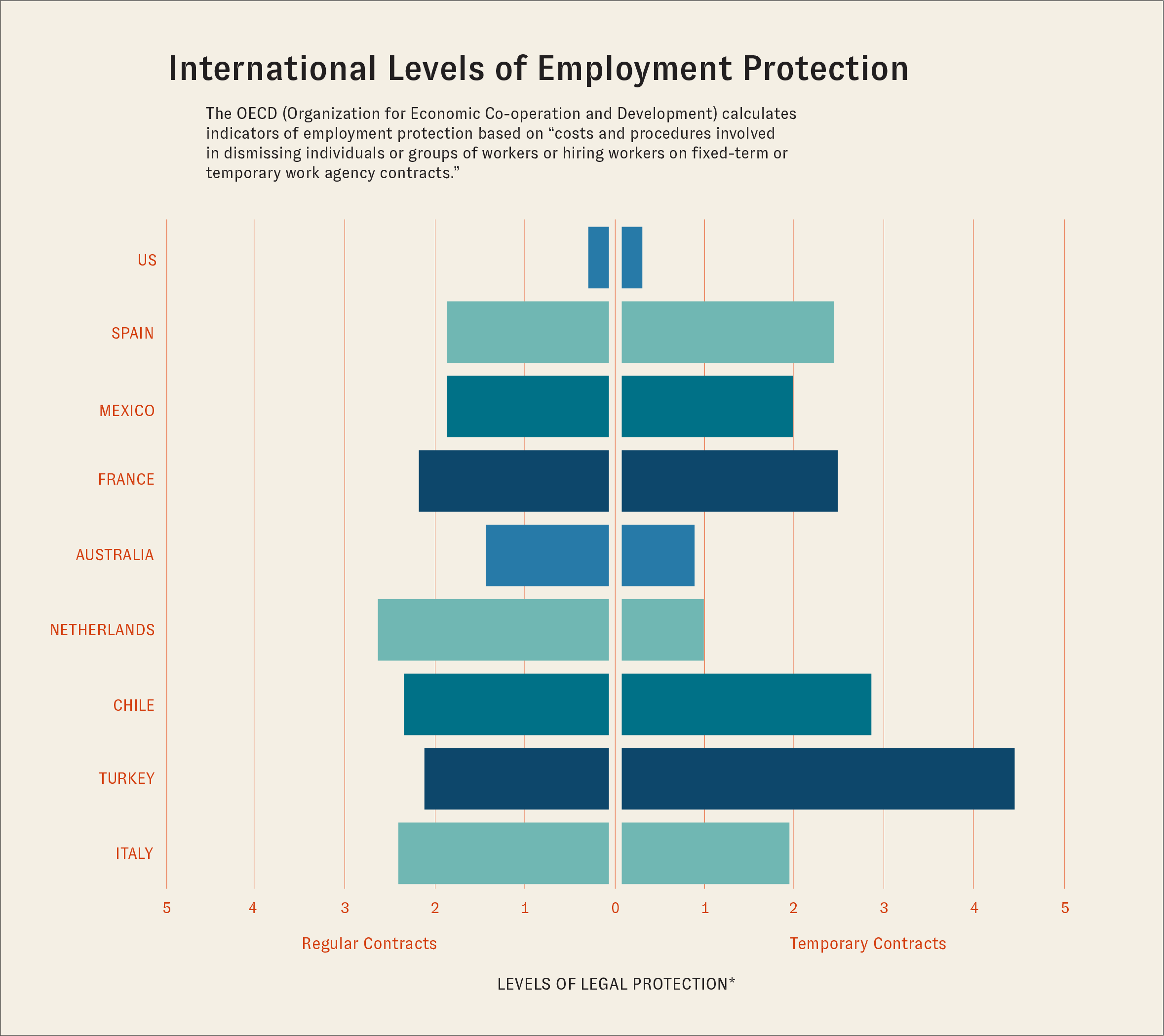

Because of attacks like these on collective bargaining power, labor protections once taken for granted are now at risk. Health care, wage stability, and other benefits have become hard to defend in this fissured economy. More concerningly, the government is growing increasingly reliant upon the private sector for health care and social security provision, meaning there’s no guarantee that gig workers are receiving the health benefits they need. Together, these trends are worrisome. A 2016 study from Pew Research found that 58 percent of full-time gig workers can’t afford a $400 emergency expense, compared to 38 percent of all other workers.

To address these structural deficiencies, the California State Senate recently passed Assembly Bill 5 (A.B. 5), a law that requires gig employers to reclassify their “contractors” as employees. The bill also entitles employees in the gig economy to receive California’s minimum wage, which will rise to $15 an hour in 2022. In comparison, Uber drivers currently earn an average of $9.73 an hour after expenses like gas and maintenance, according to an estimate from Vox.

Unsurprisingly, A.B. 5 has faced considerable resistance. Since its passage, Uber, Lyft, and DoorDash have collectively pledged $90 million toward a ballot initiative that would exempt them from the new bill. Uber’s chief legal officer has also indicated that the company will continue to classify its driver-partners as independent contractors, and Uber plans to dispute A.B. 5’s interpretation in court.

Yet even gig-employers agree that a business-as-usual approach is unsustainable. When asked about the growing income inequality between corporate executives and contracted workers, current Uber C.E.O. Dara Khosrowshahi admitted that things had “gone too far.” Khosrowshahi also acknowledged that the current social safety system is ill-equipped for today’s changing labor market.

Proposed solutions to this predicament range in scope and angle. Khosrowshahi, on the one hand, believes the government is responsible for reform. He has advocated for a new “portable benefits” system that could account for flexible employment relationships in the gig economy. Such a system would enable independent contractors to receive benefits like health care through a plan paid for by a pool of employers. Politicians have raised other solutions. Presidential hopeful Senator Elizabeth Warren wants to require that large corporations have 40 percent of their board of directors chosen by their employees. Another presidential candidate, Senator Bernie Sanders, has proposed a Workplace Democracy Plan that would eliminate barriers to union formation and codify the distinction between independent contractors and employees. Both plans are necessary responses to the profound economic transformations of our day.

While the technical details of how to protect workers from the pitfalls of the gig economy remain fuzzy, one thing is certain: Organized labor must have a seat at the negotiating table. Government officials cannot sit idly by as employers in the fissured gig-economy threaten to relegate their workers to the meager position of disposable input costs.

In 1944, the Austrian political economist Karl Polanyi wrote, “to allow the market mechanism to be the sole director of the fate of human beings…would result in the demolition of society.” 75 years later, his words still ring true—and with deafening urgency.

Infographic by Madi Ko ’21, data by Erika Bussmann ’22