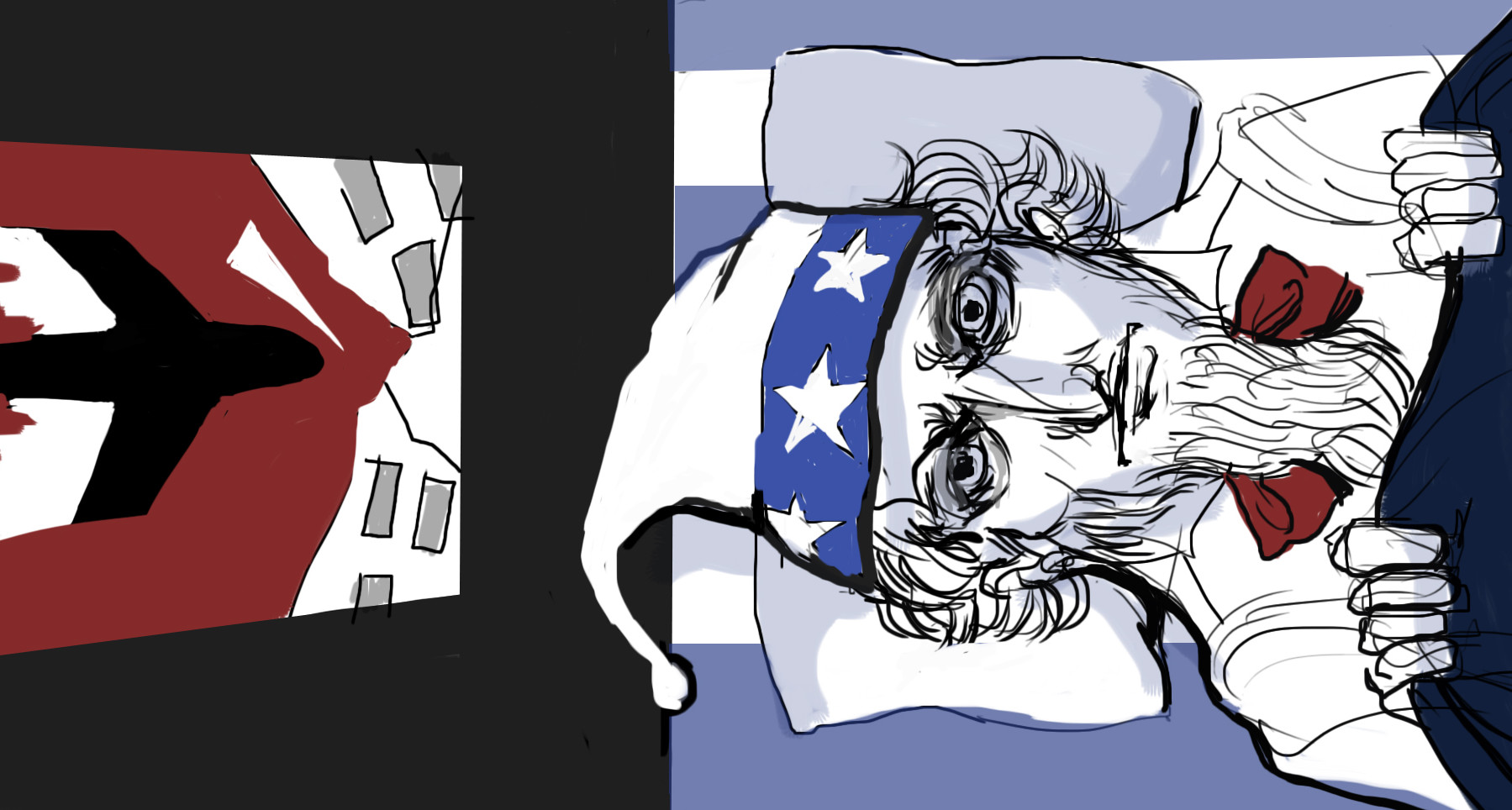

In the years after the Vietnam War ended, Americans were said to have suffered “Vietnam syndrome,” a cultural condition that led to averseness to war. Today, the American public has been defined by the advent of terrorism, which has produced a similar social effect. More than 10,000 citizens exposed to the September 11 attacks have been diagnosed with post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), an anxiety disorder most commonly associated with soldiers returning from war. Of the troops coming home from Iraq and Afghanistan, 12 to 20 percent have been diagnosed with PTSD, and their stories have increased awareness of the visceral impact that war can have. Individuals with PTSD were once dismissed as hysterical, nervous or simply insane. But while our society has come to accept and offer help to those with the disorder, many PTSD survivors continue to experience feelings of alienation, which compounds the symptoms of the illness — much like our war-weary country itself.

One of the diagnostic conditions of PTSD is avoidance.

The rocky past of U.S. foreign policy has demonstrated that the American government is far from a well-mannered beast. Take, for example, the U.S. Navy’s conquest of the Philippines in 1899, and the subsequent deaths of 200,000 to 400,000 Filipinos, or the bloody CIA-funded Contra wars in Nicaragua. Over the years, the United States managed to kill more than 250,000 Muslims in the Middle East. While the violence isn’t new, the threat of terror has significantly influenced the U.S. political process and our method of militarism, framing and justifying external violence in a context reminiscent of the Cold War fears of communist regimes — but this time, with more nebulous and globalized threats.

Many Americans prefer to forget this past. The dismissal of state-sanctioned violence is no more unique to our country than the ideology of exceptionalism is to any powerful nation. Exceptionalism is the driving force behind these dismissals; it allows us to recreate America’s past through rose-colored glasses. Yet the problem is worth examining. Terrorism falls into the historical pattern of American forgetfulness that arises when we ignore violent patterns. The many instances of past domestic terrorism that Americans choose to forget mirror the avoidance that characterizes PTSD.

Earlier instances of terrorism in America produced polarized reactions. In 1910 the Los Angeles Times building burned to the ground. The crime was ultimately traced to the McNamara brothers, both members of the Iron Workers Union. The union had turned to violence as a negotiating tactic, but a mistake meant that the bomb went off before workers had left the building. Twenty-one people died. The McNamaras were eventually captured, but many labor leaders stood in support of them; when the brothers pleaded guilty, they were accused of betraying the labor movement. The range of responses to this event distinguishes it from 9/11, which cultivated widespread patriotism. But the McNamara affair only illustrated a divide in society, as some even encouraged the violence.

Theodore Kaczynski, the Unabomber, identified his own activities as terrorism. Throughout the course of his infamous career he killed 23 individuals by sending bombs to universities and airlines. If the McNamara brothers are the extreme of today’s liberal left, Kaczynski is the opposite. In his manifesto he claimed that leftist governance had created an over-mechanized society that suffocated freedom and destroyed individual power.

These are just two examples of pre-9/11 terrorism, and they were met with reactions radically different from the reception of the Twin Towers’ fall. Modern terrorism has certainly changed our perceptions; no sensible journalist would sympathize with the cause of the Twin Tower bombers because of their violence and hatred for the United States. Yet Kaczynski and the McNamara brothers were also violent, and both sought to radically change and destroy governance. The fact that today terrorism is viewed as a quality solely endemic to people from the Middle East shows a systematic culture of avoidance that has grown out of American exceptionalism, and which allows us to overlook the history of white domestic terrorism in America.

Kaczynskis and McNamaras are more similar to the average American than they are often portrayed. The Liberty City Seven of the Sears Tower plot, the underwear bomber, the Fort Hood shooting — none of these instances perfectly fit the radicalized Muslim stereotype. In this there is a new type of avoidance, as we ignore the developments of post-9/11 terrorism that should have changed our perceptions.

Rhetoric with regard to terrorism is racially charged, even though Ted Kaczynski was a white atheist, Terry Nichols of the Oklahoma City bombings was a white Christian and Jim Adkisson of the Knoxville church shooting was a white neoconservative. No matter what the real terrorist looks like, the pictured image continues to be of a poor, Middle Eastern, Muslim male. Not only does empirical evidence contradict this particular stereotype, but even within Middle Eastern, Muslim countries, women are actually more likely to support terrorism than their male counterparts, and the poor are less likely to be jihadist.

Furthermore, we have become numb toward international acts of terrorism. We prefer to picture terrorism as an act specifically against the West, when the reality is far from it. Numb to the effects of violence from our own catastrophic collective experiences, coverage of the more than 35 terrorist attacks abroad that occurred in July of this year was minimal.

Another diagnostic condition of PTSD is anxiety.

Terrorism as a global phenomenon has profoundly impacted American culture. It has made a tangible impact on our daily lives by increasing security and surveillance — and not just on airplanes, but in most public settings and through our use of technology as evidenced by the recent furor over the NSA’s domestic spying program.

The modern threat of terrorism is both innovative and global. Terrorists’ tools are new, even if the concept of terrorism is not. Terrorists can come from any nation, including one’s own. And so terrorism emerges as an entity that is both ostracized from our society and always among it. This level of uncertainty produces extreme anxiety: we like answers.

Public opinion is fundamentally shaped by that nebulous enemy. The events of 9/11 were not just an attack on American soil; they were an attack on the idea of America. In 2002, Michael Howard in Foreign Affairs called the event “an insult to American honor” and dismissed the idea of declaring war on terrorism because it “confers on [terrorists] some kind of legitimacy,” giving them “a status and dignity that they seek and that they do not deserve.”

Howard’s commentary can be viewed through the lens of post-crisis hysteria: America was shocked and awed. While they may seem overly nationalistic, Howard’s opinions aren’t signals of a new historical trend. This kind of dismissal isn’t far-off from the racialized arguments that have marred U.S. actions even in recent decades. General George MacArthur’s underestimation and consequent miscalculation of the power and organization of Chinese and Korean forces in the Korean War was similarly due to racism and dismissive stereotyping. This reflects our modern terrorist stereotype: a Middle Eastern, Muslim terrorist that is easily identifiable and easily defeated.

Our current view of terrorism harkens to Peter Berger’s social constructivism — relying upon framing and categorization mechanisms in order to construct a coherent view of the world. But it’s also important to remember that the way we rely on these social categories is more than just a coping method against terrorism. Instead, it’s an active process of socialization. If culture can be determined by patterned ways of thinking, by the ghosts of society’s fears and hopes that dominate our very actions, then terrorism is the maker of an entirely new culture. This new generation of Americans — not just Generations X and Y, but a complete reconfiguration of the American psyche across all ages — lives in a world marked forever by the events of 9/11.

Adding to our mass anxiety, Americans have experienced a major loss of faith in security in the last decade — and a concurrent loss of faith in the enemy. Philosopher Carl Schmitt famously theorized that politics is a product of a relationship between enemies that value one another. With terrorism, though, the enemy is neither identifiable nor respected. This sets the stage for intense anxiety over our enemies and leads to the unjust warfare that Schmitt opposes.

The final diagnostic condition of PTSD is negative recurrence.

Mass media may be just as guilty as policymakers in our collective PTSD. Through oft-repeated media messaging and cultural cues, we have become adjusted to the reality of terrorism. And in our anxious comfort with the new, dangerous status quo, we have also become numbed to terrorism — both in our own history and global current events.

But the impact of terrorism’s emergence as a real threat does not end with numbing or with anxiety. Fear of the terrorist is a recurring, thematic element in a variety of cultural contexts. One of these is an expanded rhetoric of patriotism and accompanying xenophobia.

American culture portrays threats and horrors as ubiquitous, surprising and foreign. Black Hawk Down, Iron Man, The Hurt Locker and Captain America — all tell the story of singularly motivated terrorists, and these movies generally focus on the otherness of the terrorists as well as the simplicity and hatred driving their efforts. This discourse doesn’t recognize the more complex psychology and motivation behind most attacks, nor does it portray terrorists as what they often are: one of us. Terrorism discourse has even been borrowed for advertising, like PETA’s Turkey Terrorist ad, which depicts a renegade turkey threatening violence and seizing a grocery store. Our national rhetoric, whether it’s from social or traditional media, has increasingly been focused on terrorism and its implications. Terrorism has subtly infiltrated even the most mundane forms of media, causing Americans to re-experience fear of terrorism in our daily lives.

If the goal of terrorism is to disrupt American society, it has succeeded. Since 9/11, we’ve seen a precipitous drop in terrorism as a global threat, but much of our lives are still framed in the context of it — whether we are actively avoiding it, worrying anxiously about it or being subconsciously inundated with its imagery. As our veterans cope with the after-effects of their time spent in the theater of war, we too face certain stresses arising from our experiences with terrorism. PTSD may be defined as a disorder that affects individuals. But American society is experiencing its symptoms. Maybe the next time we are on the brink of war, we will recall George H.W. Bush’s restraint and address Americans’ “PTSD syndrome.”

Art by Goyo Kwon.