Spoiler alert: Check out what you can do to keep the conversation going here.

It’s almost impossible not to be cynical, reading the Times story about the White House and America’s young billionaires-to-be. Have you seen it? 100 twenty-somethings, with no particularly noteworthy life achievements besides being the imminent inheritors of their parents’ billionaire fortunes, were convened at the White House to, you know, talk about stuff.

The White House charmingly cloaked the event under the auspices of “young philanthropists” simply “networking” to make “change happen.” Right. “Philanthropy” must be the reason why the White House invited one such young guest who is the heir to the fortune of a hotel chain that has publicly vowed to fight a minimum wage increase that would be so “extreme” as to take the country back to a 1980’s-level wage floor. “Philanthropy” must be the reason why the White House kept the event off the public schedule and allowed zero reporters to attend – wouldn’t want to suffer the PR blow from all that philanthropic goodness, after all. Confused? You know, “philanthropy” – spelled D-O-N-A-T-I-O-N-S. Philanthropy.

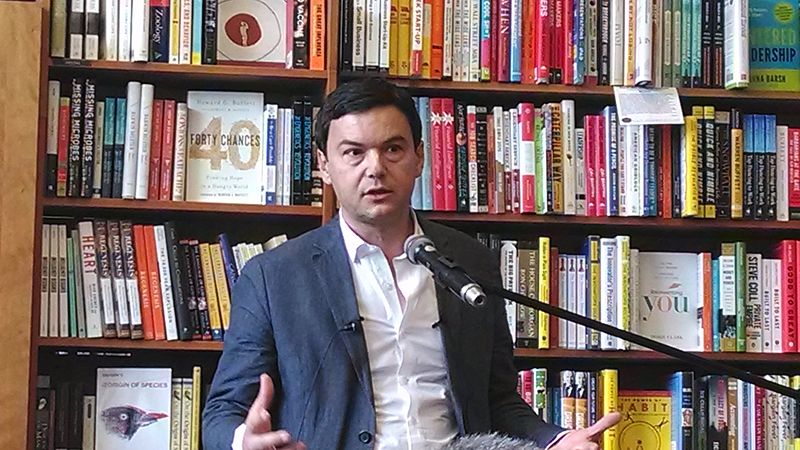

Take the Times story in conjunction with all of the buzz surrounding Thomas Piketty’s magum opus, “Capital in the 21st Century,” which has catapulted to the top of Amazon’s book list (yes, ahead of Game of Thrones). Some have already called it the book of the decade. Piketty makes the case that wealth in the U.S. is becoming concentrated to levels of world-historical significance – not entirely novel there. But where economists are fawning is his next conclusion: that as we approach a threshold of generational turnover, the preponderance of that wealth concentration will be inherited, not earned – very novel. Even Paul Krugman, not one to volunteer failure, has acknowledged that he “wasn’t thinking” about the issue that way at all. The next thirty years, according to Piketty, is a story about hyper-concentrated wealth among a generation that did nothing to earn it.Someone at the White House has been reading Thomas Piketty. Sadly, if not shrewdly, they’re drawing a very different set of conclusions than the one the author intended.

Is there a clear solution here? I grab by the collar anyone who will pretend to listen and shout tell them about the Lessig Plan for campaign finance reform – a work of policy mastery at least as innovative as Piketty’s insights, and one that I think actually has a chance of working in the American system. And the movement for campaign finance seems to be picking up steam in small, seismic rumblings (George Packer recently recommended it as his first choice of reform when testifying before the Senate).

But it’s not just about campaign finance reform. At a certain point, it can’t be about policy alone, whatever the fix. How we talk about class, and the political and (general) privilege it affords, may be more important – after all, between culture and policy, only one begets the other. Our ethical sensibilities tend to be reactive – repugnance, for instance, at reading the Times piece (seriously, if you’re not biblically pissed off, you may have a blood pressure disorder). But our strategic sensibility – the desire to bring victory to our moral tribes – is predictive, and does a pretty good job with the whole toning-down-of-the-ethics thing. However good the White House’s intentions (and we’re making a very generous assumption there) there’s little ethical gag reflex limiting the Moby Dick-like effort to capture the class influence it needs to survive, even if that influence is in the form of potential energy. Welcome to the Second Gilded Age, crossbred with the predictive instinct of campaign finance: The child of a billionaire is now transformed into a de facto child billionaire, for the purposes of political courtship.

That’s as much a cultural statement as it as a policy one, and it deserves a conversation. I don’t know what the conversation was like at The White House, but I’m willing to bet it did not look anything like the one being organized by Brown Political Forum.

The BPF’s event, “Class at Brown and Beyond,” will gather seven Brown undergrads to speak frankly about their perceptions and experiences with class. Then they’ll pass the microphone around, and then – no one knows what will happen. The forum event is open to the Brown community. The event’s slogan, “This Campus Needs to Speak,” seems to touch on the community zeitgeist at the moment. And if you don’t think that it does, we only need to be reminded of Obama’s child billionaires, and the lack of cultural dialogue that occasions it, to realize why it’s worth talking about.

Personally, I hope the event touches on the generational outlooks and impulses, not just ones at Brown, that breed our perceptions on class and power – whatever those may be. If you’re looking for me, I’ll be in the back with the free food.

* * *

On Saturday, April 26th, from 2-4PM, the Brown Political Forum will launch its student-only Community Forum series with a Community Forum titled “Class at Brown and Beyond.” At Saturday’s event, students will hear from student speakers (Floripa Olguin, Fiora Macpherson, Wendy Rogers, Khalil Fuller, Oliver Hudson, Alex Drechsler, and Zach Ingber) who will not act as experts on class, but will instead speak to their individual class experiences and what those experiences mean for institutions like Brown and society at large. Following these short addresses, attendees will engage in small and full-room discussions addressing the following questions and more: What is class? How do race, nationality, immigration status, gender, language(s) spoken, geography, and education influence class status? What does it mean to be middle class? What does class privilege look like and what should you do if you have it? How does your class status influence your experience at Brown and in the world? How can major societal institutions support the success of people from a variety of class backgrounds?

No prior knowledge of this subject is necessary and all perspectives are welcome.

This event will be catered.