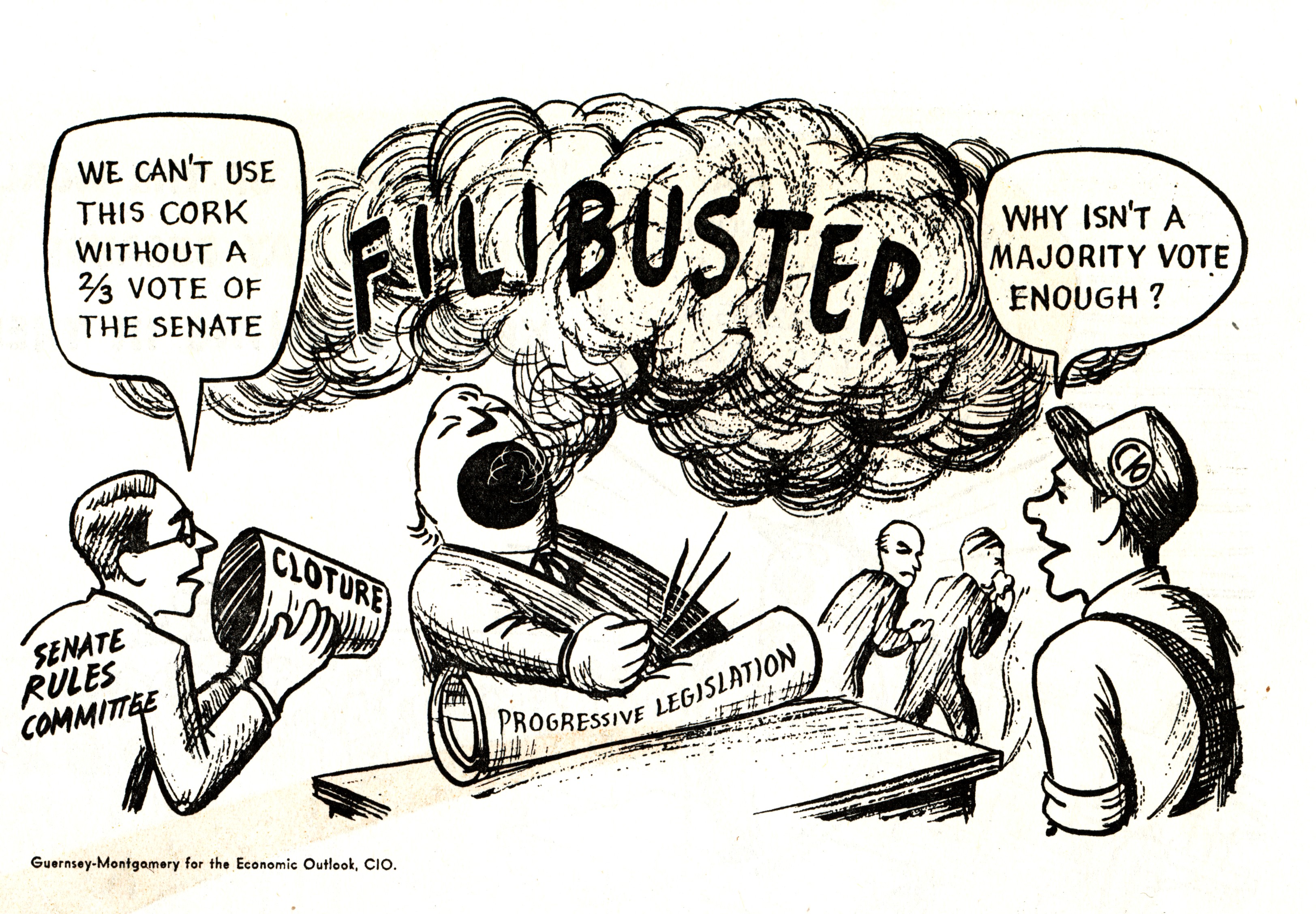

The 113th United States Congress has earned the dubious distinction of the least popular in recent history. As recently as August 2014, Gallup measured Congress’s approval rating as a dismal 13 percent. In 2013, Public Policy Polling conducted a survey that found Americans prefer the IRS, Wall Street and even Nickelback to their legislature. While the results of these polls are abysmal, it is not hard to identify the root of the public’s frustration. The 113th United States Congress is on track to enact a record low amount of legislation. Governance in Washington has become so dysfunctional that Americans are forced to suffer shutdowns, fiscal crisis after fiscal crisis, depleted highway funds and lawsuits against the president. A major cause of the stalemate is the filibuster, normally a procedural technique reserved for controversial legislation, which has been employed as a matter of routine. With the midterm elections rapidly approaching, political operatives are mobilizing voters with the promise that they will put an end to the gridlock by capturing complete control of Washington. It is a tantalizing idea for a country clearly yearning for change, but unfortunately it seems unlikely that either party will achieve the 60 vote supermajority necessary to sideline the filibuster. The deadlock currently gripping Congress is unlikely to dissipate without some form of restructuring that eliminates this tool.

The problems in Congress are partially the result of the partisan divide between the two constituent chambers and the presidency. Even if the Republicans recapture the Senate, therefore controlling the entire legislature, D.C. will still operate under divided government with a Democrat occupying the White House. The 2016 elections are the first where either party could reasonably hope to gain control over the whole governing apparatus. Unfortunately, the true formula for an obstruction-free Washington is more complicated than simply achieving unified party control of the Capitol due to the increasing prevalence of the filibuster. This fact is quickly apparent when examining the statistics. Between 1840 and 1900, there were 16 filibusters, whereas from 2009 to 2010 there were more than 130. Nowadays, any pending Senate legislation is assumed to require 60 votes to pass rather than a simple majority. The prominence of this once obscure legislative maneuver creates yet another obstacle to smooth governance in Washington, and it has often blocked legislation with broad popular support.

The last time either party had a filibuster-proof majority was during the 111th Congress, which incidentally was also one of the most productive in recent years, in terms of legislation enacted. The Democratic Party enjoyed control of the presidency and both chambers after the 2008 elections, and gained their supermajority on July 7, 2009, after Arlen Spector (PA) switched parties and Al Franken was finally declared the winner of a disputed election in Minnesota. They lost this status on February 4, 2010 after Scott Brown took his seat from Massachusetts. Even though this happened fairly recently, neither party is likely to approach the 60-vote threshold in the near future.

Many current predictions for the upcoming midterm elections forecast a Republican gain of anywhere between four and eight seats in the Senate. Everyone agrees that this will be a difficult year for the Democrats, who are defending 21 seats to the Republicans’ 16. To make matters worse for them, the Democrats are trying to hold on to seats in six states that President Obama lost in 2012, sometimes by huge margins. The Republicans only have one senator in a similar situation, Susan Collins of Maine, and her reelection is virtually guaranteed. But even in the Republicans’ best-case scenario, the GOP would fall well short of the 15 seats needed to gain a 60-seat majority. For the 2014 election at least, neither party will completely command the Senate.

The 2016 election season will likely feature many close races as well, though circumstances may be more favorable to the Democratic Party. The GOP will be forced to protect the gains they made in 2010, one of their best elections in several years. Republican senators in Wisconsin, Illinois, Ohio, Pennsylvania, Florida and New Hampshire will be defending their seats in states won twice by Barack Obama. An additional boon to Democrats is that not one Democratic seat will be up for reelection in a state Obama lost. At this early stage, it appears 2016 offers an opportunity for Democrats to recoup their likely losses from this year. The 2018 election will see the pendulum swing back yet again, with the Democrats defending their unlikely gains from the 2012 election in states like Missouri and North Dakota. It is too early to say which party will control the Senate, but it is apparent that neither party has an obvious path to build a filibuster-proof majority. Even if there’s a major wave election, it is unlikely to affect the Senate as much as the House or the Presidency. Since only one-third of the seats are up for election at a time, the Senate is somewhat insulated from reversals in political fortunes. Given the almost routine deployment of the filibuster, it is clear that neither party is prepared to break the Senate logjam in the near future.If neither party will likely command a filibuster-proof majority anytime soon, the only way to improve legislative productivity in the Senate is to adjust or even eliminate the filibuster. There’s certainly precedent for such drastic measures: the House of Representatives removed the tactic from its rules and Senate Majority Leader Harry Reid limited the filibuster’s use in judicial nominations. Neither party, however, is likely to seriously pursue eradicating the filibuster entirely from the Senate. Both Republicans and Democrats understand that their place of fortune in the majority can change in an election cycle. Politicians may feign a reluctance to alter historical institutions, but the filibuster is not enshrined in the Constitution, lending it less legitimacy than other practices, like the election of Senators by state legislators, that have fallen by the wayside. While it could be argued that the filibuster was intended to shelter minorities from majoritarianism, it now appears to be little more than a historical anomaly. Indeed, it challenges the notion of majority rule that is central to our political system. The main argument for retaining the procedure centers on its use as a protection against tyranny of the majority. The Senate, however, already flouts the concept of majority power. In a Senate election, a voting citizen in Wyoming wields more than 60 times the power of one in California. Removing the filibuster would not greatly affect the Senate’s status as a more deliberative, less majoritarian body than the House of Representatives.

The gridlock in Washington is both unpopular and deleterious to the nation. The country is facing many serious problems, and little if nothing is being done to address them. While eliminating the filibuster would not solve the gridlock problem, it would go a long way to help untangle the mess in Washington, and since neither party is likely to enjoy complete control of the Senate, altering the filibuster is the only reasonable course of action. With our infrastructure crumbling, our economy sputtering and an immigration crisis worsening every day, our politicians cannot afford many more stalemates and failures. The future of the country depends on them.