According to the president of Germany’s Central Council of Jews, Europe is experiencing its worst wave of anti-Semitism since World War II. Media saturation of conflicts in Israel seem to correspond to increases of anti-Semitic violence in Europe. In France last summer during the Gaza conflict, pro-Palestinian protestors attacked Jewish stores and a synagogue, while chanting “kill the Jews,” and an even more terrifying allusion to the Holocaust, “gas the Jews”. Rome, Great Britain and Germany have all experienced increases in anti-Semitic graffiti and hate speech as well. However, incidents of anti-Semitic targeted attacks are not confined to the borders of Europe. College campuses in the United States have seen anti-Semitic attacks and displays from organizations with supposedly purely political intentions, as well.

The concurrent timing of increasingly hateful demonstrations directed at Jews is often attributed to the increasingly tense nature of the events in Israel. However, the tendencies of such hate speech and graffiti to attack Jews, as well as Israelis, show that the hate crimes reveal more than just a political stance about Israel or its government. They are rooted in a long-standing anti-Semitic attitude. While most peaceful political protests target the country of Israel, the acts of violence and aggression target Jews.

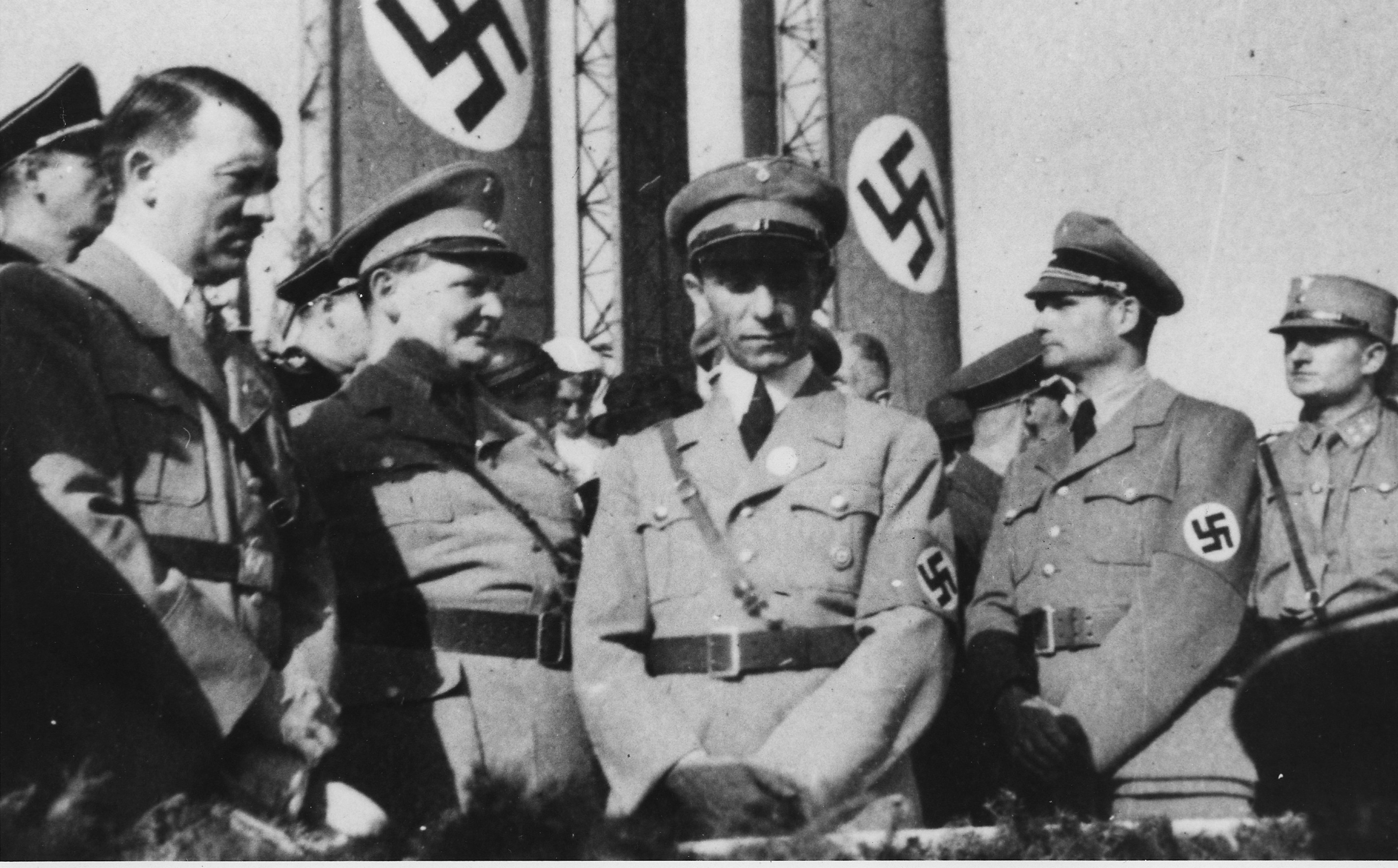

To categorize these bursts of hatred occurring in Europe as responses to recent events in Israel would ignore the historical context of anti-Semitism in Europe, which did not start nor end with the Holocaust. The role of the Jew as an “outsider” in Europe predated Shylock and survived Hitler into the present era, where in its most extreme form is manifested in Holocaust-deniers. In its most common form, however, it exists as an attitude much harder to confront; a general dislike for Jews. In 2012 the Anti-Defamation League found that 35 percent of French citizens, 22 percent of German citizens, 39 percent of Italian citizens, 60 percent of Spanish citizens and 20 percent of citizens of the United Kingdom believed Jews “have too much power in the business world.” The existence of these prevailing anti-Semitic sentiments, which consist of prejudices not against Israel but against specifically Jews, mixed with the current politically heated tension surrounding Israel, makes for an environment conducive to acts of violence.

Accordingly, this negative attitude against Jews is manifesting in anti-Israel protests. Most pro-Gaza protests are peaceful and do not take on anti-Semitic undertones, but the ones that involve violence and heightened levels of aggression are taking on an edge that seems more directed at Jews than Israelis. While protests centered on actual political discourse tend to target the state of Israel, protests that involve more anger and violence tend to target the Jewish people. This past summer in London, for example, thousands of pro-Palestinian protesters peacefully gathered by the Israeli embassy and chanted, “Stop the bombing” and “Free Palestine.” In Paris, however, protests at two synagogues and in a Jewish neighborhood escalated to the point where protestors set an Israeli flag and a car on fire and clashed with the police.

Additional examples of religious violence abound, such as in the Netherlands where a chief rabbi’s house was pelted with stones — not the house of the Israeli ambassador. Four people were shot at a Jewish museum in Brussels, not an Israeli museum. And instead of a firebomb attack on an Israeli embassy in Germany, a synagogue was targeted.

While more rare in the United States, an anti-Semitic attitude has crept up under the veil of support for Palestine, as well. College campuses, commonly regarded as safe bubbles of tolerance and progressive liberal values that push acceptance in spite of differing characteristics such as religion, are home to many pro-Palestinian groups and protests, and incidents of anti-Semitic acts. Although Jewish students make up a disproportionally large percentage of the student bodies in some of the most prestigious colleges in the country, with 25 percent of students at Harvard and 27 percent of students at Yale being Jewish, a 2011 study by the Institute for Jewish and Community Research found that more than 40 percent of students felt the presence of anti-Semitism in their colleges.

With the events that transpired in Gaza over the summer, many were worried about heightened anti-Jewish attitudes students might aggravate this fall, leading Hillel International to publish a “Student Guide to Staying Safe on Campus.” In its introduction, the guide discusses an increased prevalence of anti-Israeli activities on campus that contributes to hostile and unsafe environments for Jewish students. The guide includes instructions for identifying and responding to hate crimes, handling anti-Semitic attacks and staying safe on campus.

Last spring alone, several targeted incidents demonstrating hatred towards Jews in American colleges were reported. At New York University, members of Student Justice for Palestine (SJP) slipped fake eviction notices under doors in a predominately Jewish dorm, causing students to feel unsafe in their own dorm rooms. At Vassar College last spring, President Catharine Hill announced a review of the school’s SJP after members displayed a poster from 1944 depicting Jewish caricature wearing a Star of David and Ku Klux Klan hood, while holding an American flag and stomping on a European city. More examples of the anti-Semitism college students are experiencing illustrate the difference between hateful religious activities and respectful political organizations and the dichotomy of anti-Semitism in supposed havens for progressivism and tolerance.

Just as how most European pro-Palestinian protests are peaceful, most work done by student activist groups in support of Palestine is intended to raise awareness about important global issues and does not target Jewish students. However, when such student-run and professional political groups do break away from academic discourse and peaceful conduct, it is important to notice that their words and actions stray from anti-Israeli positions and take on anti-Jewish tones. While most of the time anti-Zionist protests are peaceful and political, they also serve as a convenient mask for preexisting anti-Semitic attitudes, and even an excuse for hate crimes against Jews.