According to the National Science Foundation, women earn 57 percent of all bachelor’s degrees in the United States and “about half of all science and engineering degrees since the late 1990s.” Yet representation in the field is lower than degree obtainment.

The age-old argument about representation of the sciences is still a valid one: Young girls are indeed more receptive to pursuing the sciences or math if they are able to see more female representation in those fields. This can vary from hiring more female math teachers to highlighting the number of contributions made by women in the sciences throughout history. However, this female representation is evidently lacking in the field. Google recently noted, due to public criticism, that 62 percent of Google Doodles honoring public figures were white men. In an article in Scientific American, Google Vice President Megan Smith and Director of People Analytics Brian Welle cited that though women hold about 30 percent of STEM jobs, less than 20 percent of female characters in television and movies are depicted in these careers.

Furthermore, young girls are often dissuaded from pursuing higher education and careers in science, technology, engineering and mathematics. Apart from the usual stereotypes that girls are less inclined to succeed in math and science, a new study in Science suggests that women in the United States “are less likely to pursue fields in which success is thought to arise primarily from raw aptitude, rather than hard work.” According to the study, society has predominately attributed the “genius” trait with men but not women. Moreover, the idea of that one must possess a raw intelligence or natural inclination to the sciences may have led several generations of women to not pursue these fields altogether. Fields in both the sciences and humanities that are considered to require the most raw intelligence have the lowest representation of female PhDs, while those perceived to require the lowest levels of raw intelligence have the most (music versus psychology, for example).

This is only one part of a cultural shift that needs to occur in order to encourage more young women to enter STEM fields. Problems still remain when women do enter universities to study math and science, from lack of mentorship to department culture. Women are steadily losing the desire to remain in these fields that they once chose to pursue. Lack of encouragement from existing mentors has deterred women from climbing the ranks in STEM; historically, women in math and science have been dissuaded from applying for doctorate programs due to an unfoundedly perceived lack of potential. Furthermore, women in the sciences are subject to severe harassment. In fact, harassment among women in STEM led to the Twitter hashtag #ripplesofdoubt, where women shared their experiences of sexual harassment, stalled career advancement, and overall disrespect in their fields. One woman even compared her personal experiences to hazing.

As if personal harassment is not discouraging enough, one study shows that having a female name on an application for a university research position makes it less likely to get accepted. Another study finds that research papers with female authors are cited less than ones with male authors. Women are not being taken seriously in math and science, even after they’ve gotten to the point where they have immerse themselves in these fields and proven that they could study it in the realm of higher education.

Researchers Jane Margolis and Allan Fisher conducted a longitudinal study at the School of Computer Science at Carnegie Mellon University, where they found that women who chose to major in computer science felt like “misfits” compared to their male classmates due to a belated interest in the field or what they perceived as a not as intense passion for it. This study highlights the school’s decision to pivot their curriculum to be less technical when attempting to retain people in the major, to be more inclusive of the experiences of women, and to try to dispel the idea of what a computer scientist is in the minds of people today.

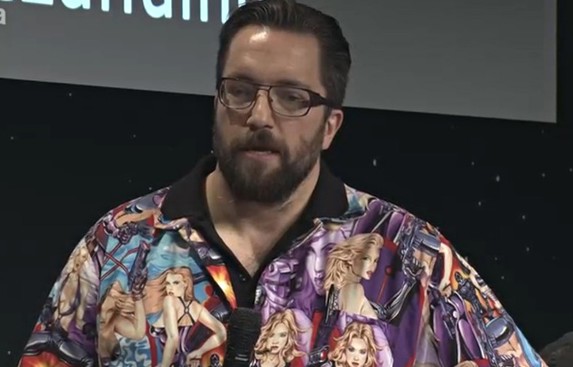

Yet there still remains a not-so-subtle trace of sexism in STEM. Consider #Shirtgate: When the European Space Agency landed a space probe on a comet, Matt Taylor, a project scientist, spoke to the news media wearing “a bowling shirt covered in pinup style drawings of scantily clad women.” Scientists turn to social media to complain about Taylor’s poor choice of attire, stating that it was offensive to women, and while Taylor went on to apologize for his clothing choice, the story does not end there. Most of the scientists who took to social media to complain about the shirt and misogyny in the sciences overall were subject to a slew of insults and attacks by other social media users. Male scientists such as Phil Plait (Slate’s “Bad Astronomy” blogger) noted that he could “tweet about the sexist shirt worn by a scientist [and] get thoughtful replies,” while writer Rose Eveleth was “monumentally harassed” for doing the same. The idea that women facing sexism in STEM should take remedying it into their own hands is not as simple as it may seem. Whether it’s “just a shirt” or something more serious, such as not receiving the same mentorship as a man, women scientists remain concerned that their troubles will fall onto deaf ears.

This phenomenon is not limited to the sciences. Members of the gaming community like Zoe Quinn, Anita Sarkeesian and Felicia Day often discuss the lack of female representation in the video games. One controversy regarding this issue, now known as Gamergate, occurred after video game designer Zoe Quinn’s ex-boyfriend claimed she had affairs with gaming journalists to receive positive reviews for her games. The consequential harassment that Quinn endured led to a wider discussion on sexism in the video game industry; however, it did not prove to be an effective conversation. Sarkeesian was scheduled to give a lecture at Utah State University; however due to her opinions on gaming feminism, the school received an anonymous threat to open fire at the University during the talk. Sarkeesian cancelled the event. Felicia Day, an actress and online personality who talks about video games, comics, and other nerd-like pastimes on the YouTube channel “Geek&Sundry,” was victim to doxing after sharing her concerns about inclusion in gaming. While these women faced frightening reactions for their critiques on the culture of gaming, men who shared a similar opinion to them, such as Wil Wheaton, received considerably fewer insults and no threats to their safety. This is indicative of a lot of spaces where men still retain the predominant opinion.

Although this picture of women in STEM seems bleak, strides have been made to encourage more young girls to pursue the sciences. Campaigns by companies like Verizon to encourage young girls and their parents to not turn their backs on the field, as well as initiatives like the NSF’s ADVANCE program are among many programs committed to reversing this trend. From women retaining professorships and leadership roles at colleges across the country to special funding for programs encouraging women to pursue STEM, the path has been forged to increase female representation in math and science. Nevertheless, STEM still has a long way to go to be inclusive —for all who are involved in the field and for those who wish to be.