On January 11, 2016, labor unions watched the Supreme Court hear a case that could decide the fate of collective bargaining. Friedrichs v. California Teachers Association was brought forward by Rebecca Friedrichs, a California teacher who requested an exemption from paying her mandatory teachers’ union dues. Friedrichs and her lawyers argued that the dues violated her First Amendment rights because unions discuss political ideologies in collective bargaining. But after the sudden death of conservative Justice Antonin Scalia weeks later, the Court came to a standstill. The Friedrichs case tied 4-4 and unions maintained the ability to impose mandatory union dues.

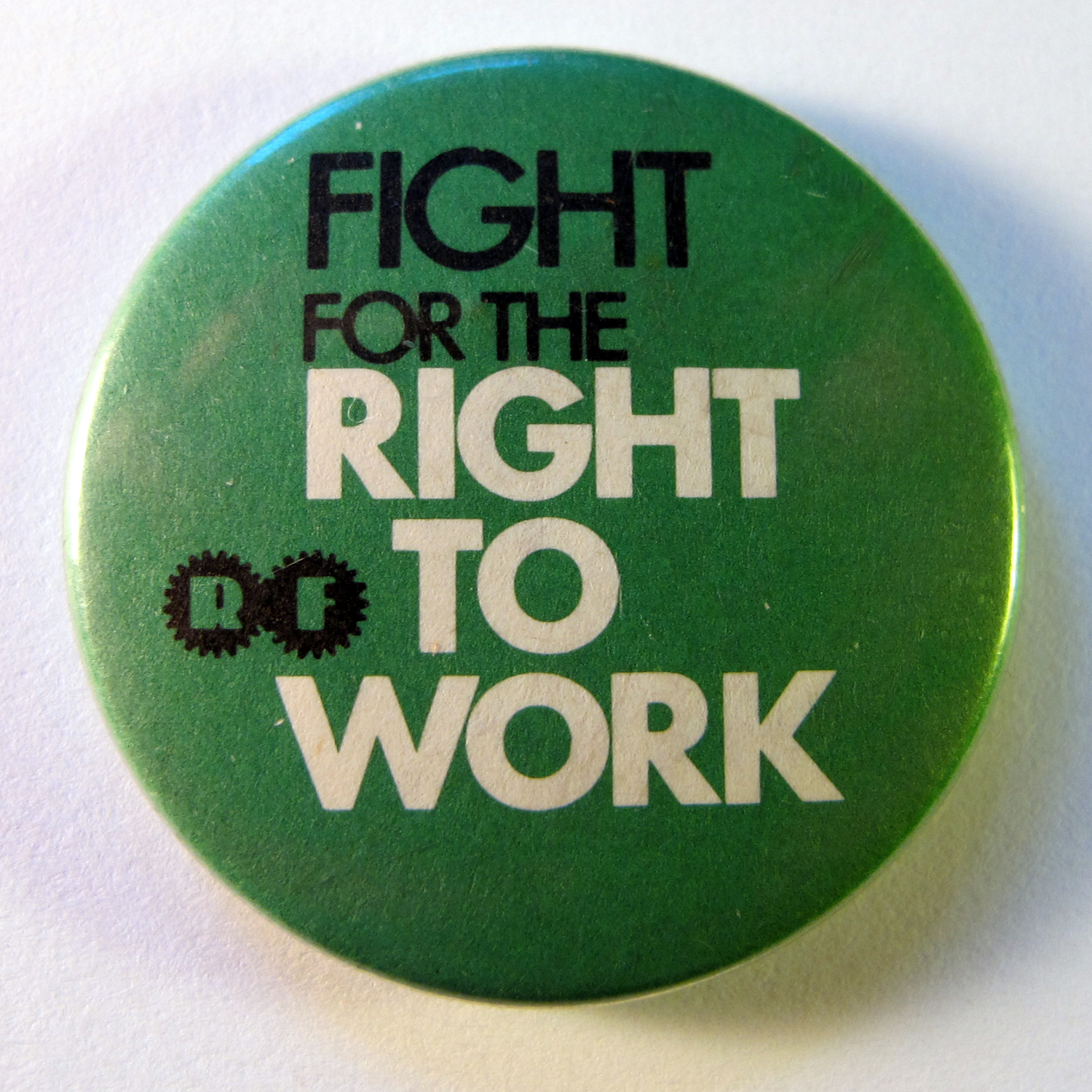

The age of compulsory union dues looks to be coming to an end. Right-to-work (RTW) laws – which prohibit unions from mandating that nonmembers pay dues – have spread like wildfire across the country. They have been met with staunch union resistance, but only now, with the impending addition of a new conservative justice to the Supreme Court bench, does a fatal blow look imminent. Friederichs’ lawyers have already filed a new suit, Yohn v. California Teachers Association, and their prospects for success are high. However, ending compulsory union membership, while concerning to the unions themselves, would not be as harmful to workers as advocates claim. Despite the undeniable good that unions have done over the course of the 20th century, right-to-work laws promote economic growth and can even help unions.

Labor unions have officially been in the US since 1886, although their roots can be traced back to the guilds of the Middle Ages. Responsible for the collective bargaining and representation of individual employees as a larger, more powerful entity, unions have long depended on their ability to compel workers to join. The reason is simple: Without compulsory membership, non-union members could “free ride” on the benefits of union members, reaping the rewards of collective bargaining without contributing dues. Federal law has helped address the free-rider problem since the early 1930s. During the heart of the Great Depression, President Roosevelt passed the National Labor Relations Act (better known as the Wagner Act), allowing for companies to enter agreements with unions, some requiring membership as a condition for working.

But in the intervening period, legislatures have taken a hard turn away from mandatory union membership. While the Depression created a groundswell of support for unions, that support began to wane following the end of World War II. The Taft-Hartley Act of 1947 repealed and counteracted much of the pro-union Wagner Act, banning closed shops and giving state governments the power to outlaw union and agency shops. This type of legislation came to be known as right-to-work (RTW) laws. Since 1947, right-to-work laws have been adopted into 28 state constitutions or statutes. RTW advocates have also picked up steam in the last decade, after a litany of conservative victories at the state and local level.

These right-to-work laws have promoted economic growth compared to states with stricter agreements. A study from the US Bureau of Economic Analysis found that from 1977 to 1999 the gross state product (GSP), the market value of all products and services created in a state, saw a 3.4 percent annual growth in RTW states opposed to only 2.9 percent in non-RTW states. This half-percent GSP benefit in RTW states may seem small, but over a 23-year period, it means that states with RTW have grown approximately 11.5% more than those without. More recent data from the Bureau of Labor Statistics shows that between 1990 and 2014, total employment grew more than twice as slowly in states with compulsory dues as opposed to those with RTW laws. Though this is not an exclusively causal relationship, the wealth of data linking job growth and RTW suggests that these laws do, in fact, attract economic activity. Businesses want to operate in regions and states where labor relations are flexible and positive: A study from 2003 found that every auto factory built in the decade prior had been built in a RTW state. As long as some states allow for compulsory union dues, states with RTW laws will continue to see an influx of businesses relocating to within their borders. A national RTW policy would similarly make the US more prosperous and more competitive with overseas manufacturers.

Some groups might contend that RTW laws undermine unions by encouraging free riders, but this trepidation is misplaced. Since RTW laws do not prohibit unions, but merely make them optional to employees, free riders present a market incentive to unions to grow stronger. When there is not a steady stream of compulsory dues, unions must fight and work to earn the support of the workers through high quality representation. Contrary to popular belief, right-to-work laws can instead lead to strengthened unions and better-represented employees.

Nevada, for instance, has had RTW laws in place for decades while still maintaining powerful unions. In 1952, the state passed right-to-work laws by a slim margin. After two subsequent attempts to have the laws repealed, the unions, laborers, and state looked at how to best work together for success for all parties. The result has been a particularly fruitful relationship between labor and business leaders. The Nevada union Culinary Workers Local 226 provides an excellent example: Since the 1980s, it has more than quadrupled its membership, and 90 percent of the 60,000 members of the culinary industry opt to pay the non-mandatory union dues. Forced to bargain as best as possible for its members in order to attract paying members, the unions have stepped up and thrived. Right-to-work laws ensure the unions are working in the best interest of the laborers by making them work for the dues – and workers are better off as a result.

Beyond just economic questions, though, right-to-work laws can help stop violations of workers’ individual rights. The very institutions that purport to work on behalf of the laborers can harm them in a multitude of ways. A key aspect of freedom of association is one’s individual right to not associate. Much like how freedom of speech protects a citizen’s right to say or not say what they choose, one has the right to associate or not associate with whom they choose. It is this right that the union shops violate most egregiously. By imposing union dues on workers as a condition of employment, union shops violate employees’ First Amendment right to freedom of association by coercing them into association with the union. The Supreme Court prohibited the use of compulsory dues for political activities in the 1988 decision of Communications Workers v. Beck, ruling it in violation of the First Amendment. The ruling allowed laborers who were not members in a union to submit an “opt-out” form of dues that will be used for these activities, but still required them to pay dues to cover collective bargaining. These have now become known as “Beck Rights.” While this decision marks an important step in protecting workers’ individual rights, it ultimately doesn’t go far enough, which is why right-to-work legislation remains so important.

Support for right-to-work laws doesn’t discount the gains unions have won for workers since the early 20th century. But times have changed since the passage of The Wagner Act, and many states have adjusted to new economic realities. The rest of the country would do well to follow. And as the example of Nevada demonstrates, right-to-work doesn’t necessarily preclude the maintenance of strong, representative unions. Rather than being the default options, unions should have to fight to deliver benefits and thereby win the support of workers; otherwise they could be easily lulled into a sense of complacency. The specter of the free-rider problem doesn’t justify suppressing economic growth nor, more egregiously, hurting the same groups unions profess to protect.