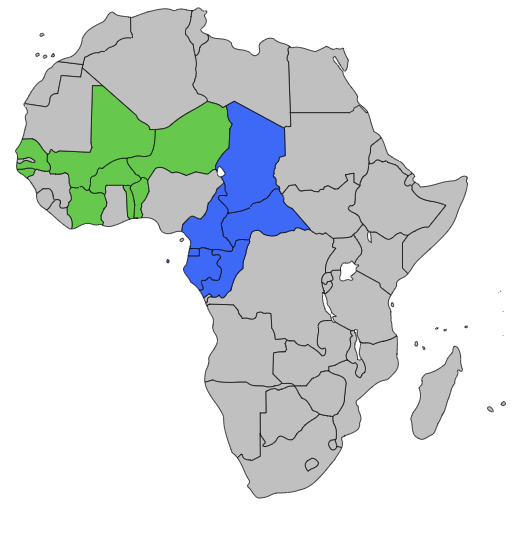

On December 26, 1945, France ratified the Bretton Woods agreement. With that act, the French created the “franc of the French Colonies of Africa.” The French Finance Minister at the time said of the franc, “In a show of her generosity and selflessness, metropolitan France, wishing not to impose on her faraway daughters the consequences of her own poverty, is setting different exchange rates for their currency.” A little over a decade later, the franc was given a fixed exchange rate with the French currency, which was converted to a fixed exchange rate with the Euro in 1999. Today, the CFA franc is the currency of 14 countries in Africa, which comprise roughly 15% of Africa’s population. Beyond its use as a currency, the franc is a monetary policy that ties the currency of African countries into European monetary policies, stifling the autonomy of these countries. This has led to a growing protest movement in many West African Economic and Monetary Union (WAEMU) and Economic and Monetary Community of Central African States (CEMAC) countries; protesters argue that they would be better off with a different currency. However, many of the countries that want to form their own currency should first look internally to ensure a stable transition to a new currency.

The deepest criticism of this policy, ironically, is the same Eurozone members have for the Euro: It mandates a common interest rate for all member countries. The fourteen countries of the CFA franc are broken up into two economic zones, the WAEMU and the CEMAC. Even though the WAEMU and CEMAC each have their own central banks, the CFA franc has been pegged to the Euro at a standard exchange rate since 1999, so the African countries’ monetary policies are basically set by the European Central Bank. This handcuffs a government’s ability to manage an economy in two important ways: Countries cannot cut interest rates to stimulate demand, and countries cannot devalue a currency to stimulate exports. These very problems were exemplified in the case of Finland following the Great Recession. After the global financial crisis of 2007-2008, Finland saw an 8 percent drop in growth, a drop worse than that of the Great Depression. Following this drop, Finland’s economy has struggled to recover for a multitude of reasons, including its lack of fiscal autonomy. Member countries of the franc zone face the same challenges, but, exacerbating the situation, Europe has no incentive to manipulate currency to maintain CFA franc nations’ economies.. Though the tie between the CFA franc and the Euro does reduce the risk that the CFA franc will suddenly depreciate, it hurts its member states more than it helps.

Because the CFA franc is tethered to the Euro, exporting goods is more costly than it would be if the countries were operating on their own currencies. This leads to slower economic growth and a reliance on existing trading relationships, primarily the relationship with France, which benefits France much more than the countries exporting the goods. Disproportionately relying on a high value trade exports, like gold or oil, helps mitigate the unfair advantage created from inflated export costs, but it forces these countries to become single-export economies. Countries that profit from rich natural resources often do not have banks developed enough to justify large deposits, so most investments go to European banks. In fact, CFA franc countries are required to hold 50 percent of their currency reserves in Paris, paying negative interest as detailed by ECB policy. Today, this amounts to 17 billion Euros, an amount that exceeds the GDP of most member states. This system largely benefits European importers and African ruling elites, but slows economic growth, creates a dependency on one premium export, and does almost nothing for the majority of the populations dependent on the CFA franc.

This situation poses two questions: Would these countries be better off on a different currency?, If so, is it realistic for these countries to move to a different currency? To answer the latter, it is important to look at what French leadership has said. In 2017, French President Emmanuel Macron said on the topic, “France will go along with the solution put forward by your leaders.” He has made it clear that any countries that want to leave the CFA franc are free to do so without repercussion from France. Since this statement, several countries have left the CFA franc and formed their own currency, including Tunisia and Algeria. However, Macron has not addressed the issue of the de facto veto power France holds over the WAEMU and CEMAC. Monetary policy set forth by the WAEMU and CEMAC is decided by a monetary policy committee. According to the London School of Economics, “The French representative is a voting member of this committee, while the president of the WAEMU Commission attends only in an advisory capacity.” The French would most likely be less willing to part with their control of the WAEMU and CEMAC, because doing so would mean losing control over all CFA countries at once. This does not mean there are not baby steps that can be taken, like having the president of the WAEMU commission serve in a larger role than just “advisory capacity”.

The answer to the former question is more complicated. Those who are in favor of leaving the CFA franc assert that African countries have accumulated enough foreign currency in their reserves that they no longer need the Euro for stabilization. They further contend that the CFA franc gives Europe access to raw materials as well as trade and influence in Africa, while it has only given member countries debt and slow growth. And if African countries no longer need to pay negative interest on their reserves in France, 20 billion dollars end up back in the hands of African governments, money that could be put to good use.

However, these arguments fail to recognize the uncertainty facing countries striking out on their own monetary system. Newly-established banks may not be trustworthy to many investors—the World Bank Ease of Doing Business report shows that, out of 190 countries, Cameroon ranked 166, Gabon 169, Equatorial Guinea 177, Congo 180, Chad 181, and the Central African Republic 183. The issue of wealth from within countries being invested in Europe and European banks, therefore, would remain. Besides the absence of the necessary financial organizations, member countries have no universal plan for moving forward after leaving the CFA franc. Some leaders advocate for the WAEMU and CEMAC to keep their current members and structure but to just have a new currency independent of the franc. More radically, others call for each individual country to develop their own currency. Simply changing to a new currency with the same structure would maintain the main problem that currently exists under the CFA franc—each country would still not be able to set their own policy. However, it is true that France would no longer have power over the organization, and policy would be decided by member countries instead of a country that does not even use the currency.

With that being said, individual autonomy would be more beneficial to countries currently on the CFA franc. Each country would benefit from different economic policies. In 2018, the unemployment rate of Cameroon was around 4.2 percent, with a GDP growth rate of 2.7 percent and inflation rate of .9 percent. Gabon, by contrast, has an unemployment rate of 19.6 percent, GDP growth rate of .3 percent, and inflation rate of 2.8 percent. These two economies clearly require opposite monetary policies. If the countries as a group were to achieve a different system together, the new policies would still only benefit one of the countries while hurting the other. Ultimately, moving forward without a concrete plan of how to implement another currency would be counterproductive and most likely economically devastating. Historically, switching to a new monetary system has proven difficult and dangerous for many countries: Mali even returned to the CFA franc after leaving, finding the CFA franc a better alternative than creating its own currency.

In Mali’s case, its new currency’s failure was in part due to its leftist economic system, which could not come up with an adequate way to distribute goods. However, Mali’s problems foreshadow those countries seeking to leave the CFA franc may face. Once countries control their own monetary policy, they have to decide whether to foster economic growth or implement structural transformation by changing the sectors of production in their economy. Historically, structural change and growth have been very difficult to achieve simultaneously—either structures are already in place for growth, or they must be transformed. Mali tried to pursue both policies concurrently, and in doing so failed at achieving either. Today, there is more specific research on how to achieve structural transformation that would ease the transition for countries coming off the franc. Countries, especially in Africa, now know that structural transformation should be pursued first and know how to carry out that structural transformation. According to the Brookings Institute, one of the most important economic areas African countries must transform is their capacity to export. As mentioned earlier, one of the biggest barriers for reaping the full benefits of exports for many countries in the CFA franc zone is their overvalued currency stemming from ties to the Euro. Many of these countries would not struggle with the communist allocation of resources faced by Mali and would make trade a main focus of structural transformation, so stable departure from the the CFA franc for individual countries is possible.

Before they can even discuss leaving the franc, these countries must first address their own banks. Banking reform does not happen overnight. It is a long process that is more about changing behavior than it is about imposing new rules or regulations. Through a series of incentives aimed at curating better behavior, these countries can make themselves more attractive to investors, including those within their own governments. Until banks in each country are deemed trustworthy and reliable and all countries that want to leave have an agreed-upon plan to move forward, the benefits of staying on the CFA franc far outweigh the benefits of leaving.

Though their financial institutions may not yet be ready, steps can be taken to liberalize WAEMU and CEMAC economies from the CFA franc. These countries should ask for a progressively lower portion of their reserves to be held in Paris over time, potentially freeing up billions of euros that could be put towards structural transformation; developing hospitals, infrastructure, and education; and jumpstarting economic growth. Beginning to remove or limit France’s veto power would additionally begin to address the problem of currency rigidness, allowing greater control over inflation and interest rates set by the WAEMU and CEMAC. While independence from the franc would eventually best facilitate economic growth, right now these countries must focus on taking the steps necessary to ensure they can eventually properly function independent from the franc.

Photo: CFA Franc Zone