Immediately after the terror attacks of 9/11, Congress quickly passed the PATRIOT Act to strengthen counterterrorism efforts across the CIA and NSA. Part of this law, the now-infamous Section 215, allows the NSA to collect any “tangible thing” that might be relevant to a terrorism investigation. The NSA interpreted this to allow bulk collection of the phone records of Americans, which consist of the phone numbers, durations, and times of each call. This December, unless otherwise renewed by Congress, Section 215 is set to expire. While the NSA will still be able to occasionally access the internet data of U.S. citizens due to spillover from foreign surveillance under the FISA Amendments Act, it will no longer have access to its broadest domestic surveillance ability. Overall, however, because of the privacy rights violations, ineffectiveness, and questionable constitutionality of Section 215, it’s time to let it expire. If the United States cannot guarantee a right to privacy, it also cannot guarantee the necessary protection of civil liberties under a successful democracy.

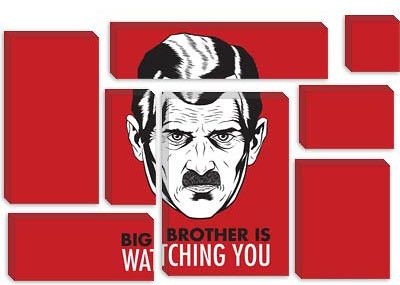

To be fair, the current version of Section 215 does not give the NSA the unrestrained power that it used to. After Edward Snowden’s leaks revealed the dramatic extent to which the NSA had taken Section 215, Congress passed the USA Freedom Act in 2015 to require the NSA to make specific queries to cell phone companies in order to access phone records. The act also required a secretive Foreign Intelligence Surveillance Court (FISC) to approve those queries. But these restrictions, while comforting on paper, are essentially ineffective in practice; the NSA still accessed 500 million phone records in 2017, and had only 12 requests rejected by an FISC. This is possible because a query can access the records of anyone “up to two hops away,” meaning the target’s contacts and their contact’s contacts. The large-scale surveillance that this enables is too dangerous to Americans’ privacy rights, and too close to the first steps of an Orwellian system, to be allowed to continue.

It is not known exactly how the program operates, but the information made available from the Snowden leaks indicates that NSA surveillance may be discriminatory, with many prominent Muslim Americans targeted as potential terrorists. For example, even though one of these targets, Faisal Gill, worked under the Bush administration with top security clearance and served in the U.S. military, his emails were nevertheless surveilled under authority from the FISA Act of 2008. The Department of Homeland Security and FBI also have histories of surveilling peaceful black activism in recent years, such as the Black Lives Matter movement. Those incidents were separate from Section 215, but they indicate the potential for unchecked discrimination whenever secrecy prevents the NSA from being held accountable.

The problems with Section 215 surveillance aren’t limited to what the NSA might do with American’s information, but also with what might happen if these records fell into the wrong hands. The NSA already suffered a major security breach in 2016, in which critical hacking tools that the NSA had used against foreign governments were stolen by hackers and turned around to target American companies. It’s possible that a foreign power could breach the NSA’s surveillance databases in a similar way at some point in the future, giving it access to the private call records of tens of thousands of Americans. All that information might then be ransomed or even published by hackers, utterly destroying the privacy of anyone involved. If the program based on Section 215 is ended, however, the NSA’s information systems would be more self-contained and secure, and would provide less sensitive information if another breach were to take place.

Moreover, if this broad surveillance authority drawn from Section 215 were necessary for stopping terrorism, it may be worth the risk to privacy rights, but research indicates that this is not the case. Under the Obama administration, the independent Privacy and Civil Liberties Oversight Board could not identify anything from the Section 215 phone record program that had “made a concrete difference in the outcome of a counterterrorism investigation” in its 14 years of existence. The independent think tank New America came to a similar conclusion. Furthermore, several weeks ago, a national security advisor to Representative Kevin McCarthy revealed that the NSA has not used the Section 215 program for the last six months, making it hard to defend any potential privacy violations in the name of national security. Even if they do lie dormant now, the NSA should not have powers that are so dangerous to privacy rights–especially if its own actions show that those powers are not necessary.

Indeed, even within the loose confines of the current law, many serious privacy rights violations have already taken place. For instance, in July of 2018, the NSA admitted that it had accidentally collected records that it wasn’t authorized to possess whatsoever. The agency could not find a way to reverse the issue, so it simply deleted every phone record it had collected up to that point. The willingness of the NSA to clear out its own metadata is yet another clear indicator that they no longer have a need for the Section 215 program. So far, presidents and members of Congress within both parties have backed the program, arguing that it is critical to catching terrorist plots before they happen. With these new revelations, however, they may reconsider the wisdom of defending a sinking ship.

Even if one assumes that NSA surveillance is both non-invasive and effective, it may not even be constitutional in the first place. The 4th Amendment guarantees Americans’ right to protection from “illegal search and seizure,” but it is still unclear just what constitutes a “search.” A recent Supreme Court case, Carpenter v. United States, determined that location data qualifies as such a right and is therefore protected from search and seizure. Such a decision could act as supporting precedent to overturning Section 215. Previously, if anyone gave their information to a third-party (such as a phone company), they lost their Fourth-Amendment rights to it. The Carpenter case revises that to specify that bulk information collection is not constitutional, and leaves open to interpretation whether database searches with specific identifiers are allowable. From the privacy perspective, phone records can be just as revealing as location data, as they both reveal activities and relationships that individuals may want to keep private. Another Supreme Court ruling may well extend the Carpenter decision to cover specific searches as well. This would overturn the district ruling U.S. v. Moalin that first affirmed the program’s constitutionality after the Snowden revelations.

Whether or not the wording of the Constitution specifically prohibits phone record database searches, the precedents that such searches set still work against the foundations of our democracy. For instance, the Chinese government’s current surveillance systems and vision of a future social credit system mean that unwanted political opinions, associations with dissidents, or even jaywalking could eventually bring about individual restrictions on travel or taking loans. China’s simultaneous expansion of surveillance and crackdown on civil liberties exemplify that if the government has the power to monitor the opinions or actions of citizens, it also has the power to repress basic freedoms. America cannot allow itself to move in the same direction.

Ultimately, Section 215 of the Patriot Act is riddled with potential for abuse of privacy rights, has not been shown to bear any fruit, and is constitutionally questionable. At this point, continuing the program come next December is simply indefensible. Counter-terror intelligence is certainly critical to national security, but at a certain point forming the beginnings of a surveillance state is not worth the ability to chase shadows. Even President Eisenhower, a former general and national security hawk, once remarked, “The problem in defense is how far you can go without destroying from within what you were trying to defend from without.” With Section 215, the United States is much closer to destroying its freedom and civil liberties from within than defending them from the dangers without.

Photo: “Big Brother“