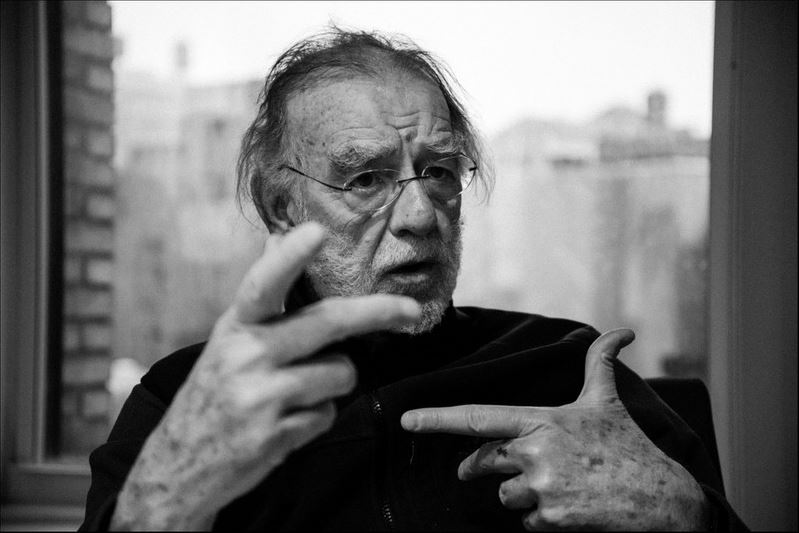

Godfrey Reggio is a contemporary documentary filmmaker who has for decades pioneered a distinct experiential film style. Born in New Orleans in 1940, Reggio spent 14 years a monk of the Christian Brothers, a Roman Catholic pontifical order. In years subsequent, he has used the medium of film to explore the destructive consequences of our technological environment. After first being featured in the Spring Issue ‘19 of BPR, we bring you a second interview, upon popular demand.

Glenn: Is death the end, or the beginning?

Godfrey: If we depersonalize — forget the “I” and consider the “we” — then death transforms into life, and so on. From whence we came, we shall return. We come and we came from the environment. It’s not by accident that we have two eyes, two ears, one nose, and by the way, most of the other creatures on the planet do too. Humans were shaped by our environment, so we became it. This cycle is manifest for those who have the eyes to see it. Yet, today, we’ve lost touch with that environment. We live in a technological cocoon. We live in wonderland.

Glenn: What is progress?

Godfrey: Progress is a loaded term. It comes from a linear way of viewing the world as with beginning, middle and end, and things constantly getting better and better. It’s the shibboleth of nation-states. It’s the shibboleth of technology. Our prayer book is to pray for more. But people live many lives and die many deaths within each life, and so I’ve never accepted the idea that we should be aiming for progress. Progress creates our wonders, constructs our Wonderland, but those very wonders have become our afflictions, and those afflictions require not fixing but another way of living.

Glenn: What do you mean when you say that people live and die many lives?

Godfrey: Life is so intense right now that people live many lives and die many deaths within a single life. That’s one way of looking at it. But here’s another way of looking at it. In the modern age, where humans have been transformed into mass-man, into numbers and statistics and indicators of progress, we might be tempted to ask the question: Do we live at all? Is there life before death?

Glenn: While watching Koyaanisqatsi at the Orpheum Theater a few weeks ago after having consumed toadstools, human society was rendered this spectacularly complex organism. The way I saw it, Koyaanisqatsi was depicting the city as a sort of circulatory system. The cars and the headlights at night as the speed through highways in long exposure were the blood. The throngs of pedestrians stopping and going between New York City intersections were the pumping. The tune of “The Grid” by Phillip Glass, itself an eerily vascular piece of music, was the system itself.

Godfrey: Like I said the last time we spoke, my films are meant to be an autodidactic experience, and in an autodidactic experience, you teach yourself how to see.

Glenn: I read somewhere that you met Paulo Freire.

Godfrey: I met Paulo Freire through Ivan Illich. I met him in Sao Paulo after he was named the Secretary of Education for that region. What gravitated me to him was my misreading of what he wrote. I loved the title, yes, but I loved the shibboleth that literacy is the renaming of the world. When saw him, I was already involved with Koyaanisqatsi. I wanted to ask him about the things I was concerned with that I didn’t see in his writings about technology as a way of living. I went to his home, but he didn’t have much to say.

Glenn: But it seems that your philosophy towards film is similar to the one prescribed by Pedagogy of the Oppressed, where Freire has this idea that the teacher ought to have an equal relationship to the student.

Godfrey: There’s a reciprocity that takes place, yes. Film is too often used to tell you what to think, and that mode of film has become so normal that it’s no longer observable. In my films, the principal subject has always been in direct relation to the audience in order that the viewer may become not a voyeur but involved in a reciprocal gaze.

Glenn: What was your relationship with Ivan Illich?

Godfrey: Ivan Illich was, if I can say it, like a brother. I was extremely fortunate to have met him when he set up the CIDOC (Centro Intercultural de Documentación) in Mexico. I was a young monk at the time, and I got permission to do my retreat down there. I was amazed by the intellect and the kind of people who were coming through there, people who were questioning the very structures in which we lived. The place was eventually shut down by the American and Mexican CIA, but I continued a relationship with Ivan through the years. He ended up in Pennsylvania with a Chair in Philosophy, and he had a group of people around him who called themselves “deprofessionalized professionals.” I never wanted to join the group after having been a monk for so long, but I always had a connection to Ivan, and over the years, he and I kept in close touch. And so I can only feel just so fortunate for that personal relationship with one of my early, early teachers.

Glenn: How did Ivan react to Koyaanisqatsi?

Godfrey: Ivan first saw the film with Wolfgang Sachs, Lee Swenson, and Hans (I can’t remember his last name but he taught at the University of Chicago and was one of the fathers of the computer), and when he did, it shocked him. [Imitating him:] “You’re raping me with my own ideas in front of me! You’re acting god-like flying above the heavens!” When he first saw it, oh, he was just freaking out. It impacted him. He had conniption fits about it. He was so disturbed by the whole experience that he ended up on Pacifica Radio attacking me for the film. It was at that moment that I was released as his student, and I realized I had my own thought.

Because Ivan had once been a priest and I once a brother, what I told Ivan was that technology is sacramental. The difference between a sacrament and a sign, you see, is that a sign is a sign of something. If you have a ring, it’s a sign of your fidelity in marriage. On the other hand, if the ring is a sacrament, it produces what it signifies. It’s transubstantiation. I told him I thought technology was sacramental — it produced what it signified — and that’s something that I think never occurred to my teacher. It was in that moment I felt in a free-way with my teacher, and more bonded with him. We went on to become close, close friends, and later in life, he even came to love the film. His name was on it and so he got a lot of response from friends, but his first experience of the film was radically disturbed. I look at radically disturbed as being a part of the film.

Glenn: What happened in his later life?

Godfrey: He went from Pennsylvania to Bremen, where he had another Chair in Philosophy. He didn’t have to go to University. His students would come to his home. He lived with a woman named Barbara Duden who was herself well known as a feminist and writer. Ivan lived out the rest of his there, near Humberg, and his students, his deprofessionalized professionals, were with him until the end. He had a growth on the left side of his face. He was like the elephant man. It went out about eight inches. On the left side, he looked perfectly normal, like a character in a movie. On the right side, he looked like a horror show. He never had it taken care of because he became an opium addict. He had prescriptions for opium in, oh, I don’t know how many countries. He traveled a lot, but he and I cemented our relationship through opium. I was one of the few people who was willing to smoke it with him which gave him great joy.

Glenn: Changing gears — in Powaqqatsi you include this haunting image of a girl driving a cart through a crowded street carrying what looks like a dead man. What’s her story?

Godfrey: At about three in the morning, every morning, that man and his daughter go to the junkyard. The man and his daughter are Christians, part of the oldest Christian sect on the planet. They are also among the poorest and most oppressed, and they’re junk pickers. They would always come back at around noon. The father is sleeping, and the young girl who’s probably eleven years old at the oldest is already a seasoned veteran at working this donkey through the streets of Cairo which, I might add, are not in straight lines like they are at Brown. We just noticed that she had a regular schedule, and it was too good not to film.

Glenn: There is a hollow look in her eyes. There’s no innocence at all.

Godfrey: Yes, there’s a real viciousness to it. You can tell it’s the traffic that’s driving her. In that sense, it’s a scene that depicts two worlds in collision.