Frustrated that neither politicians nor the mainstream media adequately addressed the dramatic rise in anti-Asian violence witnessed since the start of the COVID-19 pandemic, Eda Yu and her partner Myles Thompson created a call-to-action social media campaign, Protect Our Elders. Their campaign has collected over $150,000 in donations for organizations across the country dedicated to uplifting the Asian community. Yu and Thompson’s work to raise awareness regarding the struggles of Asian-Americans is remarkable, but social media alone will not eradicate anti-Asian sentiment. The interest in advocacy for advancing Asian-American rights must be amplified to hold policymakers and institutions accountable for their promises to support and protect Asian-Americans from race-fueled violence and hate.

Asian-Americans across the United States are experiencing higher rates of hate crimes, harassment, and discrimination tied to the spread of the coronavirus. Recent incidents have disproportionately targeted elderly Asians, including Vichar Ratanapakadee, an 84-year-old Thai-American man in San Francisco who was shoved and later died in January, 61-year-old Filipino-American Noel Quintana who was slashed in the face while on a New York City subway train, and an 89-year-old Chinese woman who was slapped and set on fire by two people in Brooklyn. Many activists directly blame the anti-China rhetoric of former President Trump, who often besmirched the coronavirus with phrases such as “the China virus” or the “kung flu.” Although Trump was the main public figure utilizing the sneering terminology, the fact that many of his spokespeople, such as former White House Press Secretary Kayleigh McEnany, defended him and refused to acknowledge the racist intents showcases the danger of the absence of accountability. Since March last year, there have been nearly 3,800 anti-Asian attacks recorded. In California alone, a state with over six million Asian-Americans who constitute 15 percent of the population, there were over 800 COVID-19-related hate incidents reported from March to May 2020.

In order to combat the rise in anti-Asian sentiment, President Biden in February signed an executive action banning federal government officials from using xenophobic rhetoric to describe the coronavirus. Additionally, in the wake of the Atlanta shooting in which a white gunman killed eight people—six of whom were of Asian descent—, President Biden and Vice President Harris met with some of the state’s Asian-American leaders. They subsequently addressed the nation via press conference to condemn anti-Asian violence and express solidarity with the Asian community. However, to quote Gregg Orton, national director of the National Council of Asian Pacific Americans, “Rhetoric alone will not solve this problem.” Such a statement highlights the relative lack of substantial action from the federal government to combat anti-Asian racism.

The federal government’s noticeable oversight has led to several states taking the lead in establishing new initiatives and allocating funding to prevent and reduce anti-Asian violence. For instance, California Governor Gavin Newsom signed the AB85 pandemic budget bill, which earmarked $1.4 million for researchers at the Asian American studies Center at UCLA to fund data collection and research for community organizations seeking to address, analyze, and eradicate anti-Asian hate. In New York City, where Asian-Americans represent approximately 16 percent of the population, the city has recently launched a new webpage titled “Stop Asian Hate” through which people may report bias incidents or hate crimes. Additionally, the NYPD has created an Asian hate crimes task force in response to a ninefold increase in the number of reported anti-Asian crimes this past year.

However, both levels must pass and incorporate more reform efforts to prevent Anti-Asian hate and harassment. One of the biggest issues government officials need to address is law enforcement’s minimal response to hate crimes against Asian-Americans. For instance, localities rarely investigate and prosecute hate crimes due to the police lacking sufficient evidence, like a video clip of the offender using a racial slur or a self-incriminating statement. Even if evidence was identified, local police agencies often lack enough training and funding to properly investigate hate crimes, which are already treated as a low priority. Furthermore, prosecutors are reluctant to charge hate crimes, fearing an inability to prove bias and thus losing their cases. State prosecutors in San Francisco exemplify this problem as they charged the assailant who killed Vichar Ratanapakdee only with murder and elder abuse. This stance further undermines confidence in the criminal justice system among at-risk communities because it perpetuates the idea that hate crimes are insignificant. Although the inclusion of a hate crime charge in the Georgia mass shooting case would not have changed the expected amount of time the gunman spends in prison, a hate crime charge serves as a significant testament to the trauma and pain inflicted on the greater Asian community.

There are also many cultural and language barriers that result in many Asian-American residents, especially immigrants, not reporting hate crimes. Although the Department of Justice has expanded the number of translated languages for its hate crime resources to include Chinese, Vietnamese, Japanese, and Arabic, many activists have called on the Biden Administration to increase Asian representation in his cabinet and assign an official of Asian descent from the Justice Department to spearhead a task force to combat the rise of violence.

Especially amid a climate of fear created by the pandemic, it is more important now than ever that policymakers pass legislation that both improves hate crime reporting and increases accessibility for Asian-Americans to feel safe and heard by institutions that are supposed to protect them. As there is now heightened attention by news media regarding Asian-American rights, politicians must seize this opportunity to galvanize support and act with swiftness by instituting necessary reforms to protect vulnerable communities and condemn race-fueled hatred. In conjunction with political reform efforts, non-Asians can demonstrate their support for the Asian community by checking in with their Asian peers, supporting small Asian-owned businesses that have been hit disproportionately hard during the pandemic, watching documentaries that discuss the United States’ long history of anti-Asian violence, and donating to local Asian-led grassroots organizations. Another viable method is through encouraging collective phone-banking, emailing, and letter-writing campaigns for their respective government representatives to pass the COVID-19 Hate Crimes Act, which would expedite the federal government’s response to the rise of hate crimes exacerbated during the pandemic, support state and local governments to improve hate crimes reporting, and ensure that hate crimes information is more accessible to Asian-American communities. Government officials and individuals must stand strongly against anti-Asian xenophobia and hate and put partisanship aside to ensure the Asian community’s safety and respect that they deserve.

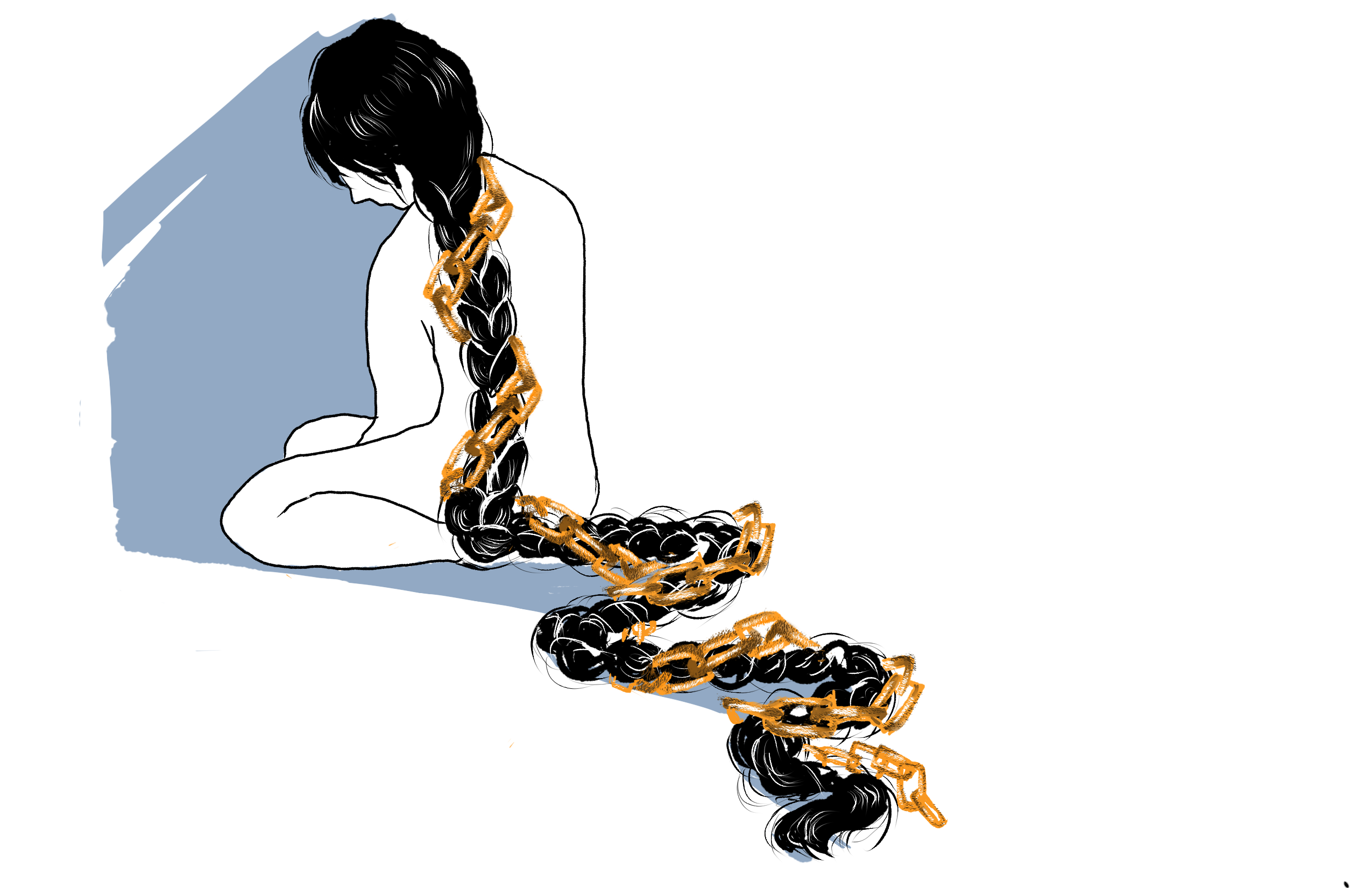

Photo: Original Illustration by Jenny Zhang