With 211 days of full school closure between March 2020 and February 2021, Panamanian schools have had a longer break from classroom learning in the Covid-19 pandemic than any other nation in the world. Even worse, a UNICEF survey conducted in November 2020 found that 41 percent of Panamanian households with children (excluding households in Indigenous comarcas, or semi-autonomous Indigenous regions) currently have less food to eat than they had prior to the Covid-19 pandemic. With in-person education on pause and food insecurity on the rise, Panamanian children in lower income households have been particularly disadvantaged. Given this disproportionate harm, the Panamanian government must act immediately to increase access to distance learning and nutrition for at-risk children. Furthermore, it must simultaneously prioritize the safe reopening of schools. In this vein, Panama must not only build stronger water, sanitation, and hygiene (WASH) infrastructure in schools to prevent the spread of diseases including Covid-19, but it must also pursue an ambitious school feeding program to address food insecurity on a national level.

Despite being over one year into the Covid-19 crisis, efforts to mitigate the burdens of distance learning and increase access to nutrition remain insufficient. In December 2020, the Panamanian Ministry of Education reported that 47,000 public school students—or about 6.5 percent of the total population of public school students in Panama—completely missed the school year because their schools were unable to contact them. Moreover, there are important quality and equity concerns, even for those students who managed to access some form of distance learning. In November 2020, a UNICEF poll revealed that only 52 percent of Panamanian public school students surveyed received their education using online platforms that allowed for interaction with teachers, compared to 84 percent of the surveyed private school students. 60 percent of public school students also recall relying on instruction broadcast on the radio or TV at some point during the pandemic. Stuck between complete educational exclusion and poor quality distance learning, Panama’s most vulnerable children are at risk of being left behind.

In addition, the Vale Digital, a monthly transfer program offering financial support to Panamanian households, has fallen short of providing adequate economic relief. The monthly price of a basic family food basket—the minimum amount of food necessary to satisfy nutritional requirements in a household—hovers around $250 USD in most Panamanian provinces. However, these transfers, which began at $80 USD per month and rose to $120 USD in February, leave families bearing the brunt of food costs. Furthermore, among families that have reported food shortages due to the Covid-19 pandemic, 63 percent declared that the type of food they now serve their children has been affected. Thus, the Panamanian government must act swiftly to protect the country’s children from malnutrition and to restore access to quality education. Committing to a timeline for reopening schools is crucial to accomplishing both of these goals. In the meantime, however, the government must expand its current economic relief package to, at the very least, make it commensurate with the price of the basic food basket.

Schools could serve as a powerful nexus between education and nutrition for Panamanian children. This potential, however, remains largely untapped. School feeding programs can yield a return on investment as high as $9 USD for every $1 USD invested, with positive externalities affecting education, health, nutrition, and social protection. Nutrition is especially critical during the first five years of life, after which the damage to a malnourished child’s development may be irreversible. The child stunting indicator, which measures the percentage of children whose height is at least two standard deviations below the world average for their age, exemplifies this tragic reality. Stunted children end up earning 20 percent less on average than adults who were not stunted as children. In addition to its impact on income, stunted growth is associated with direct losses in productivity due to poor health caused by malnutrition, as well as increased healthcare costs for chronic and infectious diseases. Stunting affects 15.9 percent of Panamanian first grade students, but this figure is far higher in Indigenous comarcas, standing at 61.4 percent and 53.4 percent in Guna Yala and Ngäbe-Buglé, respectively. These rates will only climb without government intervention.

Not only are school feeding programs an impactful solution to combat malnutrition during pre-primary school years, but they can play a fundamental role in addressing the rising threat of obesity among older children. Paired with nutrition education, school feeding programs are uniquely positioned to influence children’s diets and consumption patterns at a pivotal time in their lives. No less important, school feeding programs incentivize parents to keep their children in schools as they come of age rather than send them to work full-time. Lastly, school feeding programs have been found to have positive spillovers on local agriculture and employment, directly creating about 1,668 jobs for every 100,000 students fed. These impacts could make a powerful dent in the massive rise in unemployment brought on by the pandemic.

Despite the growing body of research undermining concerns that children and schools would be major spreaders of Covid-19, opening schools remains notably absent from the Panamanian government’s timeline for resuming in-person activities. Controversially, leisure industries, including shopping malls and casinos, were assigned concrete dates for reopening months ago. In contrast, the timeline for resuming education has been strikingly vague. In January, the Ministry of Education announced that the school year’s first trimester (March-June) would run online, with schools reopening only for small-group tutoring. The Executive Decree governing the 2021 Academic Year cryptically states that “the epidemiological conditions of each educational region will be evaluated periodically along with the Ministry of Public Health with the goal of appraising the transition to other modes of learning, in the second and third trimesters, according to the biosecurity conditions in each region.”

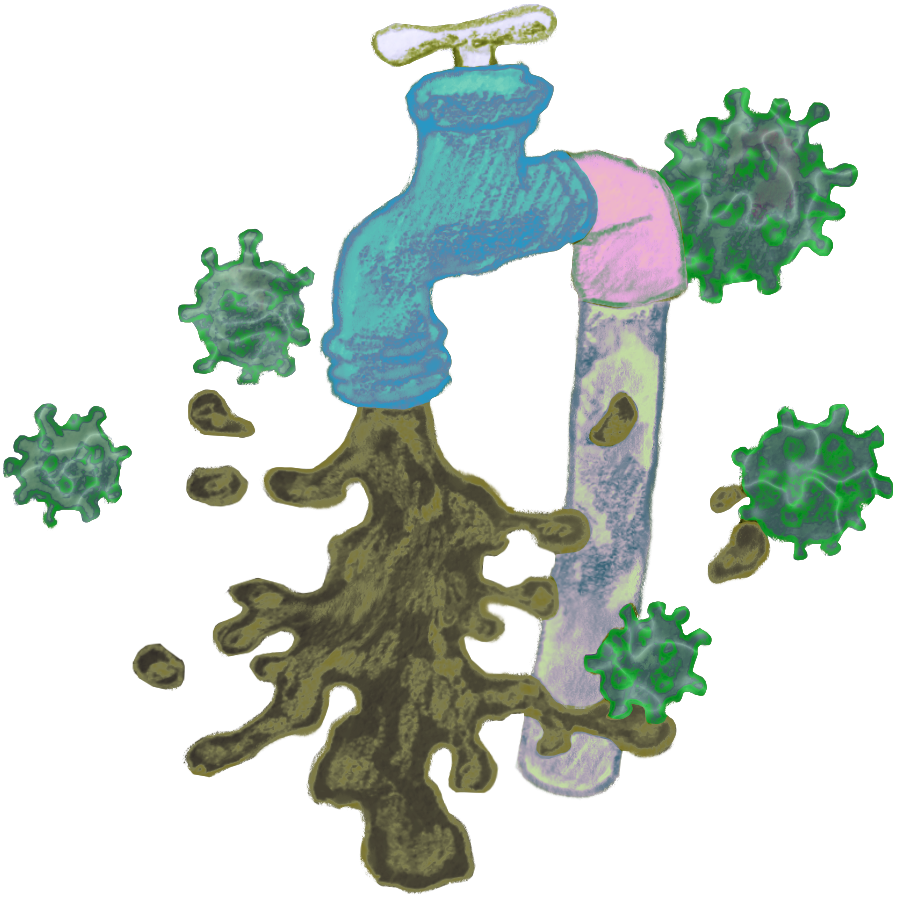

The Panamanian government has a responsibility to commit to a timeline that addresses the alarming educational, sanitation, and food insecurity problems faced by children in the country. Above all, it must first focus on increasing access to distance learning and adequate nutrition. But Panama must then work to safely return children to schools, which will require improved WASH infrastructure. One in three Panamanian public schools lack a safe, 24-hour water supply, posing a significant sanitation problem that is especially urgent during the Covid-19 pandemic. Moreover, as schools reopen, the Panamanian government should implement a comprehensive school feeding program in order to continually tackle the issue of childhood malnutrition at the national level. Prior to the pandemic, the current government sought to address this issue through a school feeding pilot program, which was approved only weeks before national school closures began in March 2020 and has yet to be meaningfully implemented. It is imperative that such efforts be resumed and expanded in this time of great need.