In 2019, a Business Insider article noted the visible difference between yellow streetlights in eastern Berlin and the fluorescent, whiter bulbs in the West. In other words, the divide between East and West Berlin is still noticeable over 30 years after reunification. The same applies more broadly to the former German Democratic Republic (GDR) and the Federal Republic of Germany (once West Germany but now Germany’s official title), where structural differences—rather than lights—have entrenched disparities between the two sides of the country. In former East-German states, unemployment is higher and income is lower than their counterparts in the West. Polling from 2020 also found that a mere 22 percent of those in the former GDR are satisfied with the current state of German democracy, compared to 40 percent in the West. These factors have broad implications for German politics and society.

One glaring reverberation of this divide has been the success of the right-wing and nationally conservative Alternative for Germany (AfD) party in the former GDR. The party’s eurosceptic and anti-migration platform has resonated with disaffected voters; in the eastern states of Saxony and Thuringia, the AfD received a majority of votes in the recent federal elections, a feat achieved by no far-right party since the end of the Nazi era.

While the AfD’s gains in the East are concerning, they have not been monolithic. Namely, in the northeastern state of Mecklenburg-Vorpommern’s regional elections, the AfD came 20 points behind the center-left Social Democrats (SPD), losing around 4 percent of its 2017 totals in the process. The SPD successfully countered the AfD’s rise by nominating a popular candidate, Manuela Schwesig, who was viewed as representative of Mecklenburg Vorpommern’s interests as an East-German state. Furthermore, the party centered both its local and national campaigns on social issues that highlighted the structural divides between East and West Germany. Such an approach worked in September in Mecklenburg-Vorpommern and the federal elections and can be used as an example for success in the future against the far-right in Germany.

The SPD and AfD received 39.6 and 16.7 percent of the vote in the regional elections in Mecklenburg Vorpommern, respectively. Yet, exit polls indicate that voter support for Schwesig, the SPD’s Spitzenkandidatin (leading candidate), was at 67 percent, compared to the Christian Democrats’ (CDU) Michael Sack, who received 11 percent, and the AfD’s Nikolaus Kramer, who earned only 5 percent. In fact, 29 percent of AfD voters indicated that in a direct election, they would have voted for Schwesig over Kramer. Given these numbers, it is not just important to know that Schwesig is popular, but why that is the case. 71 percent of voters believed that Schwesig would successfully represent the interests of their state at the federal level—the interests of a state in which 73 percent of voters believe that East Germans are second-class citizens compared to West Germans, and 66 percent of voters believe that politics and economics are determined too strongly from West Germany.

Schwesig garnered a robust following as a result of her steady leadership throughout the coronavirus pandemic—Mecklenburg-Vorpommern has the highest vaccination rate of former GDR states and the second-lowest infection rate of all German states—and by prioritizing tangible benefits that could be implemented in a short period of time. Since January 2020, daycare centers, kindergartens, and after-school programs have been cost-free, apprentices can use public transportation for one euro a day every day of the year, teachers are paid better, and municipalities can budget more efficiently thanks to new laws.

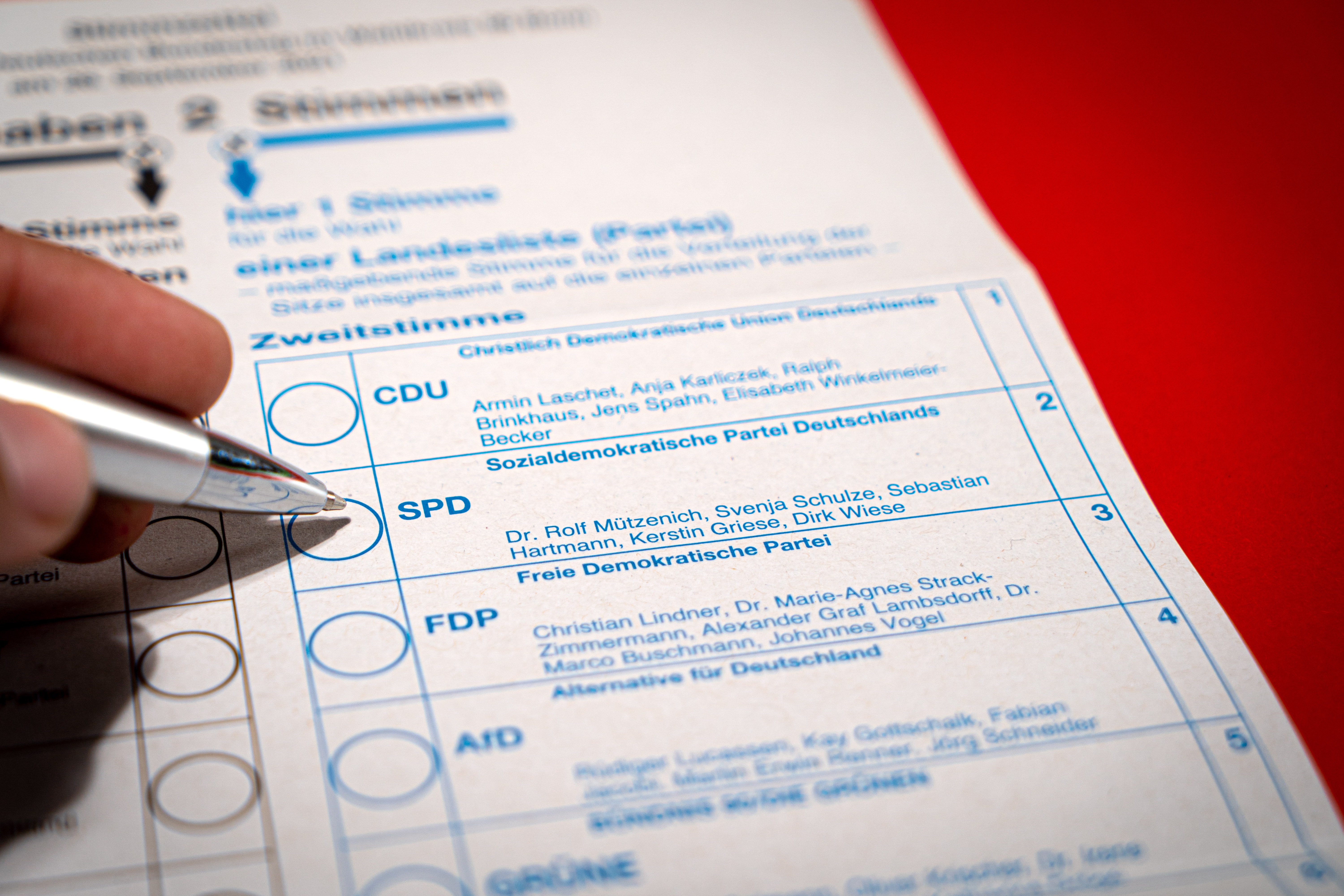

Demanding support for Schwesig as a candidate also translated to the SPD’s broader success as a party. Such a detail is important given the split-ballot nature of Germany’s elections, where voters cast a ballot for both a preferred candidate and political party. Indeed, 53 percent of voters said that her stay as the state’s minister president was the most important reason to vote for the SPD. But the SPD’s success in fending off the AfD extends beyond Schwesig and includes the party’s national platform under the leadership of former Finance Minister Olaf Scholz. Throughout his campaign for chancellor, Scholz promised an increase in the German federal minimum wage to 12 euros, along with calling for affordable housing and stable rents. Such a position was unsurprisingly favored by voters in Mecklenburg-Vorpommern, where the two most important issues for voters were the economy and social security. Not only did the SPD win the most votes nationwide, but they were the only party to have an even split of votes between the East and West halves of the country.

Former Chancellor Angela Merkel’s Christian Democrats (CDU) are Mecklenburg-Vorpommern’s third-most popular party, having received 13.3 percent of the vote in September. This result is substantially different than a decade earlier, when vote shares for the CDU totaled 23 percent. The CDU’s decline in Mecklenburg-Vorpommern, coupled with the SPD’s success both in vote tallies and in fending off the AfD, highlight why the SPD’s strategy has been so successful for the following two reasons. First, both the regional and national Spitzenkandidaten for the CDU were either unpopular or unknown in the East. Only 20 percent of voters approved of the state-level candidate Michael Sack compared to Schwesig’s 67 percent, and one-third of voters knew little or nothing about him. Moreover, Armin Laschet, the party’s chancellor candidate, is facing sharp criticism from his own party in the East due to his performance during the campaign.

Second, the CDU—having governed nationally for the past 16 years—has become less clear on their policy stances, which have even become muddled with the AfD in certain respects. In the state elections of Saxony-Anhalt in August, 81 percent of CDU voters thought that their party should separate itself more clearly from the AfD. Now, in the post-Merkel area, it is likely that the CDU will be the largest opposition party in the German parliament, and the party has already announced plans to “vote on an entirely new board, including chairperson, before year’s end.” Both of these will require the party to perform some ideological soul-searching, potentially giving East German voters a better understanding of whether or not their candidate will represent their specific interests, like Schwesig.

Support for the AfD in the former GDR can, at least in part, be attributed to the failures of parties such as the SPD and CDU during the last three decades. The next state elections in both Saxony and Thuringia are not held until 2024, which means that there is time for both the SPD and CDU—as well as other established parties—to regroup and strategize effective ways to combat far-right politics in their states. The SPD has found and proven a metric for success, and the CDU and its partners should take notes. Little explanation is needed to illustrate Germany’s history with the far-right, making it imperative that regions work together to mitigate the AfD’s influence.

Photo by Mika Baumeister on Unsplash