Aiding Sahrawi refugees requires building improved infrastructure.

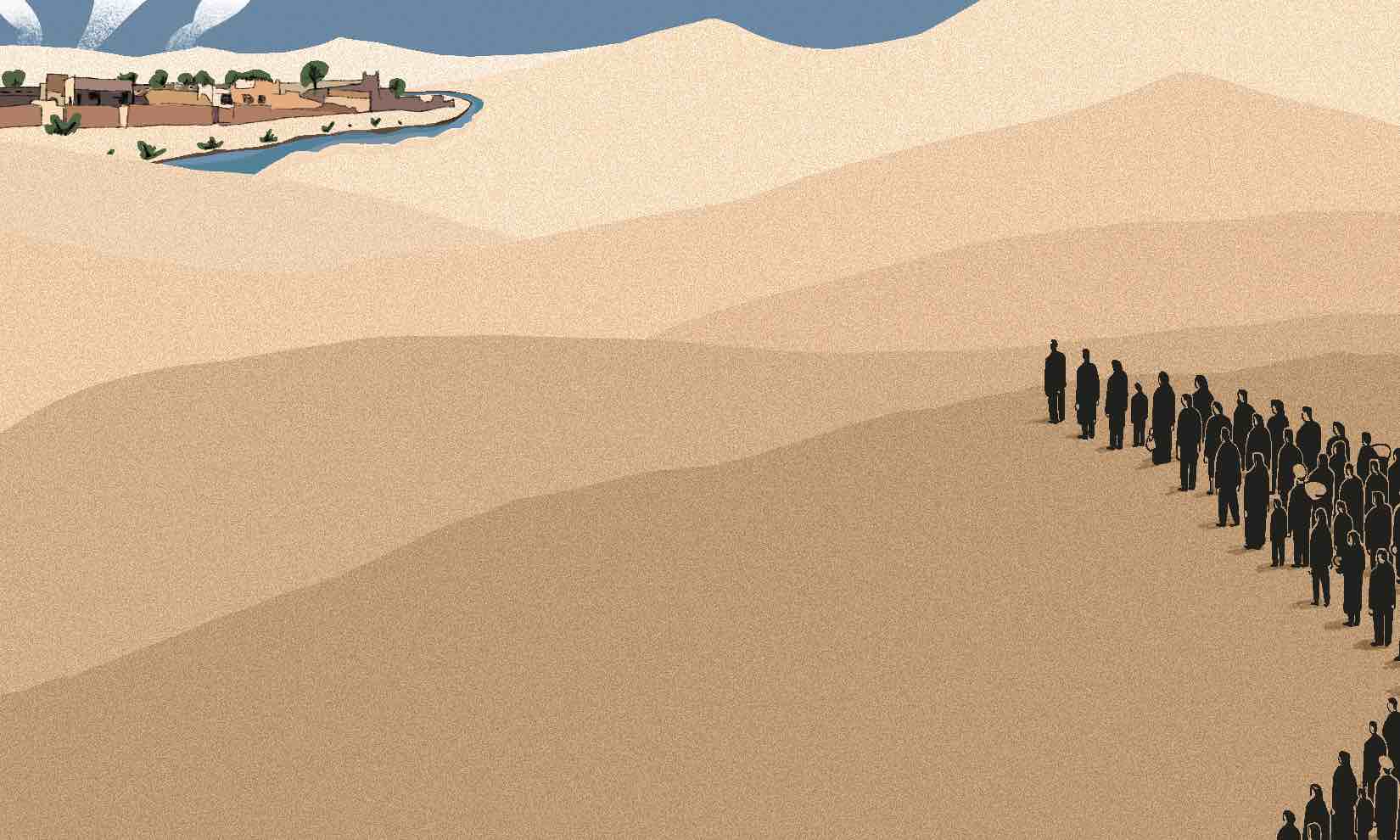

Outside the city of Tindouf, in the desolate borderlands of Algeria, an estimated 165,000 ethnic Sahrawi live in makeshift refugee camps. Forgotten, poor, and dependent on humanitarian aid for survival, these refugees—many of whom have spent more than 40 years in exile—have little hope. Today, refugee camps that were established in 1975 have become permanent settlements, yet they still lack the infrastructure needed to support the Sahrawi population. Material poverty in Sahrawi refugee camps is unquestionably worth addressing in and of itself, but poor conditions in camps are also fueling renewed violence between the Polisario Front and the Kingdom of Morocco. Therefore, the construction of sustainable infrastructure in Sahrawi refugee camps could also help revive ceasefire negotiations and bring peace to the region.

The Western Sahara conflict began in 1975, when the Spanish government signed the Madrid Accords and ended its colonial presence in the Western Sahara. In the accords, Spain ceded the territory occupied by its colonial administration to Morocco and Mauritania rather than to the native Sahrawi population. The Polisario Front—a Sahrawi guerilla group that had fought Spain for self-determination since 1973—began a war against Mauritania and Morocco with the aim of gaining control of the territory. In the following years, the Western Sahara War displaced thousands of Sahrawi and led to the creation of the refugee camps near Tindouf. Although the Polisario Front defeated Mauritania early on, Morocco still laid claim to the entirety of the Western Sahara territory, so the war continued. The Moroccan military, backed by the United States and France, maintained a consistent upper-hand in the conflict and eventually constructed a massive 2,700-kilometer-long berm, or sand wall, which it frequently patrols and has fortified with minefields. The berm has impeded Polisario fighters’ guerrilla campaign, allowing Morocco to retain nearly 80 percent of the disputed territory and leaving the war in a stalemate. While the 1991 UN-negotiated ceasefire was relatively effective, the Moroccan military obstructed a UN referendum to determine the territory’s status. Over the next 30 years, Algerian refugee camps have become permanent settlements for an entire generation of Sahrawi.

Sadly, exile has not been kind to the Sahrawi people. “You need to know one thing,” said Salima, a 29-year-old resident of the Laayoune camp, in an Oxfam interview. “I don’t like to live here. None of the residents of these camps like to live here.” Poor infrastructure in Sahrawi refugee camps has made even basic necessities like water and food scarce. A 2016 study led by the Universidade da Coru a found that, in most locations, the average amount of water supplied to Sahrawi refugees for drinking purposes fell below the minimum 20 liters per day recommended by humanitarian agencies for survival in camp conditions. But the lack of access to water in Sahrawi camps results primarily from poor water production and distribution networks, not from a scarcity of the resource itself. Despite the desert climate, local groundwater reserves near Tindouf are massive: An estimated 10,600 cubic hectometers of groundwater is available in a region that consumes around two cubic hectometers each year. While the limited number of boreholes and purification centers near Sahrawi camps is the main hurdle to water access, flawed distribution systems also inhibit such access. Water distribution pipelines service only 40 percent of Sahrawi camps, with the remaining 60 percent furnished by trucks. Unfortunately, the majority of water trucks used to supply the Sahrawi are more than 20 years old, resulting in frequent breakdowns. Even when the Sahrawi are supplied with drinking water, as one refugee noted, “we have to collect [it] from rusty metal tanks.” Creating sustainable water infrastructure by drilling more boreholes, laying additional pipelines, and updating storage tanks is vital to improving access to drinking water and quality of life in camps.

The same is true for food infrastructure. Currently, most of the food that Sahrawi refugees consume comes from rations delivered by humanitarian aid organizations. Even with this assistance, a 2018 study by the World Food Programme found that only 12 percent of Sahrawi families living in the camps are classified as food secure. Furthermore, 7.6 percent of the Sahrawi population suffers from acute malnutrition, and around 50 percent of children and young women suffer from anemia. The availability of foodstuffs in Sahrawi refugee camps is clearly inadequate. While increased humanitarian funding could address shortages, this aid would only provide a temporary solution. Compared to harvesting groundwater, developing sustainable food sources in refugee camps poses more complicated challenges. Nonetheless, the United Nations Human Rights Council (UNHRC) has suggested raising livestock, creating community gardens, and starting bakeries as ways to increase community resilience and food production. The UNHRC hopes that by fostering tighter community bonds and greater economic innovation, these food production strategies will help the Sahrawi learn valuable skills and lay the groundwork for the development of more sustainable food practices in the future.

Simply put, the most basic needs of the Sahrawi people are not being met. Poor conditions in camps have brought poverty, malnourishment, thirst, and suffering—all of which should be addressed for their own sake through the creation of sustainable infrastructure. In addition to this humanitarian cause, ameliorating conditions in Sahrawi refugee camps could also mitigate the renewed violence in the region.

In early November 2020, on a highway outside the city of Guergarate, years of discontent erupted in violence between Polisario-backed protestors and Moroccan infantry. The conflict that followed destroyed a 29-year-old ceasefire in the region. The Polisario Front then declared war on the Kingdom of Morocco, announcing that it had launched attacks against four Moroccan military positions. Soon after, Algeria, the main supporter of the Polisario Front, severed diplomatic ties with the Kingdom of Morocco. Since then, a series of minor skirmishes, alleged drone strikes, and rocket attacks have claimed an unknown number of lives.

Today, the Polisario Front is no more able to threaten Moroccan military supremacy along the berm than it was in 1991. The notion that the Sahrawi could return to their homeland through a total military victory over the firmly entrenched and better-supplied Moroccan army is simply unrealistic. Yet material desperation in refugee camps and a lack of faith in the UN’s ability to deliver a referendum have left Sahrawi with few other means to improve their circumstances. “If we wait for the UN Security Council to deliver the referendum and the freedom to go back to our land, we will be here for 300 years,” one Sahrawi youth leader named Hamdi told Crisis Group. “If we don’t go back to war, nothing will change.”

Ultimately, in negotiating a renewed ceasefire, the UN has to convince refugees like Hamdi that things can change through peaceful means. In this light, a significant commitment to building sustainable infrastructure outside Tindouf would serve not only to alleviate the suffering of 165,000 refugees, but also to provide disillusioned Sahrawi with an alternative to war and an opportunity to once again begin the peace process in a troubled region.