On May 29th, in several cities across Puerto Rico, thousands of people joined in demanding freedom for Oscar López Rivera – a Puerto Rican nationalist, independence activist and America’s longest-held political prisoner. The event, titled 32xOscar, was held on the 32rd anniversary of his unjustly long imprisonment on charges of seditious conspiracy to overthrow the U.S. government. News stations were paying attention, politicians were giving speeches and hashtags were trending (#32xOscar, look it up). Most importantly, people of all backgrounds and convictions were united in their call for justice, and in their desire to see Oscar – now 70 years old – return to live out the rest of his days on the island he dedicated his life to.

Born in Puerto Rico in 1943 and moving to Chicago in his teens, López Rivera was one of many Puerto Ricans who were swept up in the counterculture and liberation movements of the 60’s and 70’s, and who made it their mission to fight against American colonialist control over the island. Throughout the 20th century, members of island and mainland groups fighting for Puerto Rico’s right to self-determination were often deemed terrorists by the FBI, and consequently hunted down and incarcerated as political prisoners. A decorated Vietnam veteran, Oscar López Rivera came back to Chicago after his army tour, and, according to the government, was inspired to join the Armed Forces for National Liberation (FALN, in its Spanish initials), one of the many groups that were blacklisted by the feds. This independentista, or pro-independence, organization originated in 1974 and for nine years conducted a militant anti-colonial campaign that involved bombings in government buildings, military bases and corporate headquarters in the United States.

While the actions of some FALN members did lead to several deaths over the years, Rivera’s participation in any fatal or harmful events was never proven. Rivera was pursued for being a member of the group and eventually captured in 1981, a year after ten of his FALN comrades were arrested and charged with seditious conspiracy. When Rivera was caught, he, along with his fellow independence fighters, claimed POW condition under international law as an anti-colonialist fighter, and demanded to be tried by an unbiased tribunal outside the United States. Rivera and his fellow nationalist suspects argued that under Protocol I of the Geneva Convention of 1949, the United Nations afforded protection to persons captured in anti-colonial conflicts. They also pointed out that U.N. Resolution XXVIII of 1973 established that: “all imprisoned or detained participants of resistance movements, independence movements, and attempts at national self-determination must receive just treatment as stipulated in the Geneva Convention of 1949.” Several international judicial bodies eventually saw fit to recognize their claims, but the American government refused to do so, instead trying them on regular criminal offenses. Rivera, like his fellow compatriots, put up no defense during the U.S. trials due to his belief in their illegitimacy. As a result, they were given maximum sentences on all charges. Since then Rivera has been serving a 56-year sentence for his original crime, and was given an additional 15-year sentence for conspiracy to escape from prison in 1987 (another unusually long punishment). In his trial he was convicted only of seditious conspiracy, armed robbery and lesser offenses, as the prosecutors were unable to link him to any deadly bombings attributed to the FALN.

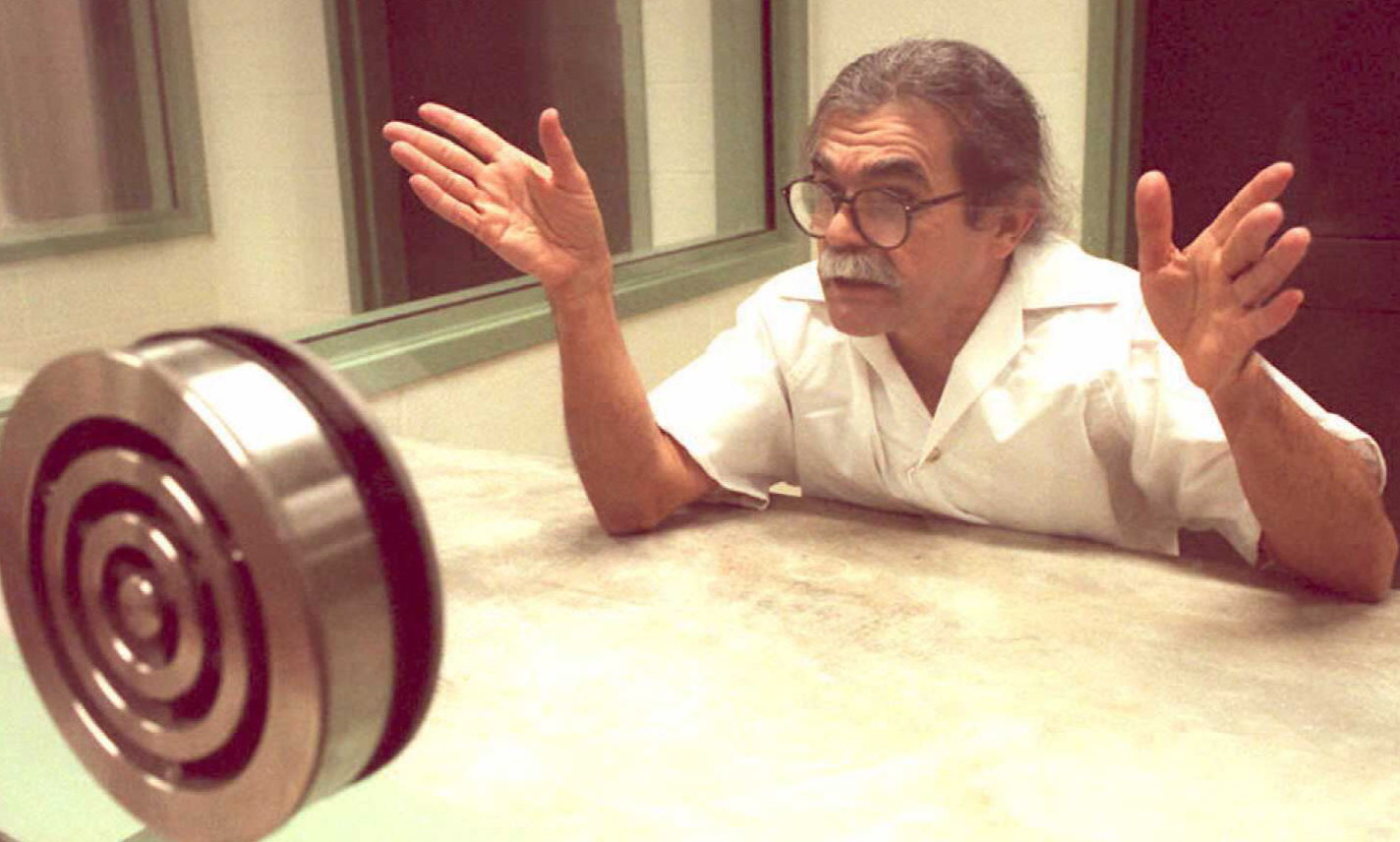

During his years in maximum-security prisons, Oscar López Rivera has been subjected to cruel treatments such as sensory depravation, unnecessary solitary confinement, and various other punishments that infringed upon his basic human rights. The authorities at the first two prisons he was kept in also harassed him constantly, depriving him of sleep and regularly confiscating his recreational reading and art materials. In 1998, Rivera was moved to a third maximum-security facility, where he has been required to report his presence to prison guards every two hours for the last 15 years, an unheard-of precaution before the Puerto Rican nationalist arrived at the prison. These conditions were not unique to Rivera, as all convicted Puerto Rican independentistas suffered similar ones at the time. Many were placed in prisons distant from their homes, which made family visits much more infrequent. Also, in a break with Bureau of Prison policy, all were denied bedside visits and funeral attendance for sick or deceased family members.

In 1999, President Bill Clinton offered an executive pardon to twelve of the fifteen remaining Puerto Rican political prisoners, under the condition that they forgo any further radical pro-independence action. The Clinton administration stated “the prisoners were serving extremely lengthy sentences — in some cases 90 years — which were out of proportion to their crimes.” Lopez Rivera was among those Clinton offered amnesty to, with the conditions that he serve ten more years due to his breakout attempt and that he keep a clean prison behavior record. Rivera declined the offer, however, stating that he would not make any deals for his freedom as long as there were other Puerto Ricans held as political prisoners. The last of the prisoners not offered amnesty, Carlos Alberto Torres, was released July 2010, making Rivera the only remaining Puerto Rican being held on charges of seditious conspiracy. No further offers for amnesty, conditional or otherwise, have been made to him.

“The hero of a nation is the terrorist of its opponent,” raps Puerto Rican rapper Residente Calle 13. The quote is particularly representative of the dichotomy of Rivera’s situation. Throughout the three decades he has been held prisoner in the United States, he has often been branded an unrepentant terrorist and murderer, despite the fact that no connection was ever proven between him and any fatal incidents involving radical independentistas. Conversely, Puerto Rico and the larger international community have repeatedly decried this abuse of American power and demanded his freedom. Various resolutions of the United Nations Special Committee on Decolonization have highlighted the need for Puerto Rican political prisoners to be released. Several special international tribunals have also demanded prisoners’ liberation and have specifically denounced the conditions they suffer through while incarcerated. Even the internationally renowned South African Archbishop Desmond Tutu has come out against Rivera’s imprisonment. If something was made obvious by the events of the 29th, it’s that a large and growing segment of the Puerto Rican community has joined the campaign for Rivera’s release. During 32xOscar, musicians, artists, journalists, athletes, academicians, politicians and other public figures from across the island (and the political spectrum) spoke out against his confinement. Puerto Rico’s governor, the President of Puerto Rico’s Senate, and the island’s House of Representatives have all written to the President asking for Rivera’s sentence to be commuted. Some years ago even Pedro Pierluisi, the president of Puerto Rico’s pro-statehood party, said, “I don’t see how they can justify another 12 years of prison after he has spent practically 30 years in prison, and the others who were charged with the same conduct are already in the free community. It seems to me to be excessive punishment.”

Some might argue that in the wake of the Boston Bombings and other events that increased fears of terrorism, no politician would risk any political capital on pushing for Rivera’s freedom. Then again, President Barack Obama owes his both his electoral victories largely to the overwhelming percentage of Latinos that voted for him. Among these are many mainland Puerto Ricans that would support a pardon for Rivera. There are also precedents for Obama to follow, as both Jimmy Carter and Bill Clinton have commuted the sentences of Puerto Rican political prisoners in the past. If the man can offer a Presidential pardon to a turkey every year for Thanksgiving, it doesn’t seem too much to ask that same consideration be given to an peaceful, elderly U.S. citizen like Rivera. Not to mention that the President has openly supported Puerto Rico’s right to self-determination, promising to respect any decision reached through consensus. These days Rivera’s name is everywhere in San Juan – from art exhibits to music festivals to mayoral press conferences. Demonstrations of popular will have taken place all over the island, and Puerto Rico’s highest-ranking officials have written letters to the President pleading his case. Evidently, Obama cannot simply shrug the issue aside while maintaining his lofty rhetoric on the island’s sovereignty. He must realize that, regardless of his words, Puerto Ricans are not free to choose their situation as long as the country they are tied to relies on Lopez Rivera’s anti-colonial sentiments as a justification for keeping him as a political prisoner.

As 32xOscar drew to a close, as the chants of “We are all Oscar” went on into the night, the words of San Juan’s mayor Carmen Yulín rang out loud and clear: “Now our day ends, but the fight doesn’t end until we welcome Oscar back at the airport gates.” This is a cause worth fighting for, a display of much-needed familial unity between the sons and daughters of an island, and one that we should all hope to advance.

What are the names of the captured F.A.L.N members of th 1970’s ?

I believe the names were: Elizam Escobar, Ricardo Jimenez, Adolfo Matos, Alfredo Mendez, Dylcia Noemi Pagan, Alicia Rodriguez, Ida Luz Rodriguez, Luis Rosa, Carlos Alberto Torres, and Carmen Valentin.

RT @32xOscar: @billmaher @MMFlint A Mandela imprisoned in the US: http://t.co/CP1N112pvz http://t.co/2Yzq2Rvhyp

And the pleas for Oscar López Rivera’s freedom continue….this one from Brown University’s student political review. http://t.co/yQrTd3FAbz