Those even remotely cognizant of the current political climate will know that the United States is currently experiencing a period of self-reflection and social activism as the country debates and grapples with its history and present reality of racism, sexism, homophobia, transphobia, classism, ableism, and more. Aided by the immediacy and interconnectivity of social media platforms, these issues have been feverishly deliberated on platforms ranging from coffee shops to national news outlets. The end result is a largely intersectional social justice movement, the scale of which hasn’t been seen in the United States in over forty years.

One of the major characteristics of this movement has been the prominence of a call-out culture; that is, the common practice of singling out individuals when they make comments or actions of an offensive and/or discriminatory nature, making it known that what they said or did can be harmful to others. This method is as old as advocacy itself but has become especially prominent in recent times. Historically, the act of calling-out can take many forms, but typically today it involves social media in some way, whether it be a Twitter hashtag or sharing articles on Facebook, the ease of which has ramped up its frequency.

The act of calling out injustices and systems of oppression is crucial in recognizing and fighting against hatred and discrimination in American society. The process fights against the societal biases and normativity that have disenfranchised, marginalized, and/or oppressed peoples and provides specific targets and incidents as focal points for protest to center upon. One example of the benefits of call-out culture can be seen in the case of former United States Representative Todd Akin (R-MO). While campaigning for the Senate in 2012, Akin tried to defend his anti-abortion beliefs extension into even the case of conception-by-rape by stating that “if it’s a legitimate rape, the female body has ways to try and shut that whole thing down.” Appalled by his comments, women’s rights activists decried Akin, pointing out the misogyny and scientific inaccuracies behind his words. Akin subsequently lost his election and thus his seat in Congress, demonstrating how call-out culture can prove successful in preventing someone with such misguided and obviously biased attitudes from maintaining a position of legislative power.

A similar occurrence took place in South Carolina last year when, in the wake of the racially-motivated Charleston church shooting, protestors successfully compelled the state government to remove the confederate flag from the Capitol Building’s flagpole. In this instance, the objectors called out the flag’s association with slavery and racism, denying the idea that the flag represented a shared heritage rather than hate. Protestor Bree Newsome even went so far as to climb the flag pole and remove the flag herself before the state decided to take it down permanently a few weeks later. In this case, call-out culture worked because it acted against a figure of power — the South Carolina government — in response to an offensive symbol.

That being said, call-out culture can sometimes do more harm than good, specifically when the subject being called-out is not in a position of power. Often, challenging and criticizing the words of those who have little or no prior influence can give them a new, more widespread platform to share their thoughts. Even if the vast majority of the attention given to them is negative, some will inevitably sympathize with and possibly even copy their comments or actions. It’s similar to if Rolling Stone were to review an obscure album plucked from the depths of Bandcamp just to write a harsh criticism of it: sure, the intention is to point out the music’s flaws, but in the end the artist will receive more publicity and the album will sell more copies than if it remained undocumented, unanalyzed, and ultimately unnoticed.

This concern is no longer merely a hypothesis, and examples of calling out backfiring have already become prevalent. Earlier this year, YouTuber Daryush “Roosh” Valizadeh, whose videos are wildly misogynistic and homophobic and who even advocates for the legalization of rape, planned a series of public meet-ups for his viewers. However, after intense public outcry, media scrutiny, and promises from women’s groups to disrupt the events, Roosh cancelled the meet-ups. While his messages are obviously incredibly heinous and disgusting, realistically the meet-ups were to be of modest size at best and were designed for his viewers — who presumably would already share his views — to talk to each other in person. The outrage around the events, on the other hand, provided Roosh and his followers with more attention than ever before, certainly more than they would’ve gotten just via the events. Even though the public reaction was overwhelmingly negative, protestors may have inadvertently spread Roosh’s messages of hate for him; indeed, since the controversy, his YouTube subscriber count has increased from about 19,000 to 21,500, or by about 13 percent. While an additional 2,500 subscribers does not constitute a massive jump, it only takes a modest gain to lead to countless suffering.

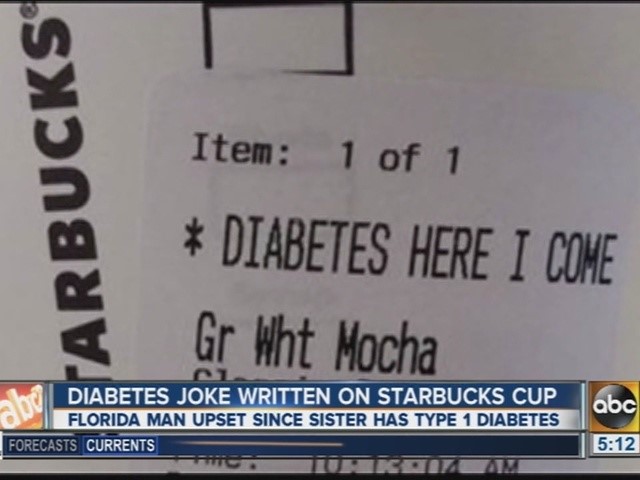

More recently, controversy arose online — primarily via Facebook — when a Starbucks employee labeled a customer’s sugary order “diabetes here I come.” The image showing the distasteful comment went viral, becoming a trending topic online for a day or two. Once again, while it’s important to note the problematic nature of comments like this in person-to-person interactions, the benefits of sharing this story over and over again seem unclear. The criticism may stop that specific employee from doing such a thing again (if he manages to retain his job), but beyond that the criticism hardly seems productive. If anything, a handful of bone-headed copycats could follow suit after finding the original comments funny, but the overwhelming amount of people who see this story do nothing, save for a quick giggle or a lackadaisical rolling of the eyes. Therefore, in this situation, and others like it, call-out culture could be seen as ineffectual at best and counter-intuitive at worst.

Furthermore, calling-out non-influential figures and handing them the spotlight in the process gives other individuals incentive to make controversial statements of their own. In other words, if someone is desperate enough for attention, even if it’s negative, they might see that saying or doing something blatantly hateful can garner the publicity they crave. It’s the same concept the has boosted Trump and Carson campaigns (to different levels of effectiveness) this election cycle; that is, using controversy and outrage to get their names out there and increase their visibility in the media and public eye. Both candidates have employed inflammatory and hateful rhetoric mainly aimed at immigrants and minorities as a way of reaching their respective levels of success throughout the election process. The increased media attention and excessive reporting on their bombast elevated their status, even causing the few people who truly agree to feel validated and become actively recalcitrant. Challenges from activists have done little to derail Trump’s campaign in particular, in many ways feeding into the persecution complex he and his supporters allege and provoking further malevolence.

Even in less significant cases, the act of calling out still has some benefits. Letting harmful comments or actions slide is never ideal, and call-out culture does an excellent job of not letting people off the hook easily. Without explicit denunciation, activists run the risk of appearing to condone these ideas via passivity. Moreover, inactivity could allow certain spaces to become hostile, as unabated statements of hate reverberate through an echo-chamber effect. But balance is key, as these potential dangers can be outweighed by the more common and more damaging byproducts of call-out culture in situations where the offender has no podium.

Call-out culture is an important and primarily helpful component of modern social activism. But misapplication of these criticisms can easily backfire, helping spread a message of hate or bias in the act of trying to squash it. Social media’s universality complicates the process, as striking a balance between recognizing harmful discrimination and avoiding detrimental identification is harder than ever. As difficult as it may be, in some cases it may be best to let these types of comments lie and die out on their own, rather than risking unintentionally fueling them. The challenging part is knowing just where that line should be drawn.

Hi Michael,

Great use of examples! I had a discussion with a friend about Justin Timberlake’s tweets about Jesse Williams’ speech at the BET Music Awards and we disagreed about racial issues. We did agree that the way that people on the internet were quick to “roast” him was not productive. The reason I mention this is because this was sort of left out in your analysis of call-out culture. While you make a good point about the risks of calling out non-influential people, you did not touch on calling out people, like celebrities, who do have influence (not in the same way as a politician, but as a cultural icon/figure). In my example, people sort of blew the situation way out of proportion (although I did point out to my friend that Justin is not innocent and that prejudice/discrimination/color-blindness are nothing new). Those who call out sometimes do it in such a way that it shuts down opportunities to create progressive dialogue and appropriate actions/chances to take accountability. What made this argument touchy was that my friend is a fan of Justin. Often times a part of call out culture within the context of the celebrity world that gets left out is that there are people who may take offense when their favorite celeb gets called out. Those people then believe that the person they admire is being unfairly put at the stake and advocate for them instead of listening to constructive criticisms aiming to make it a teachable moment. I don’t know if this makes sense to you, but I appreciate that you wrote about this topic. 🙂