by Joaquim Salles

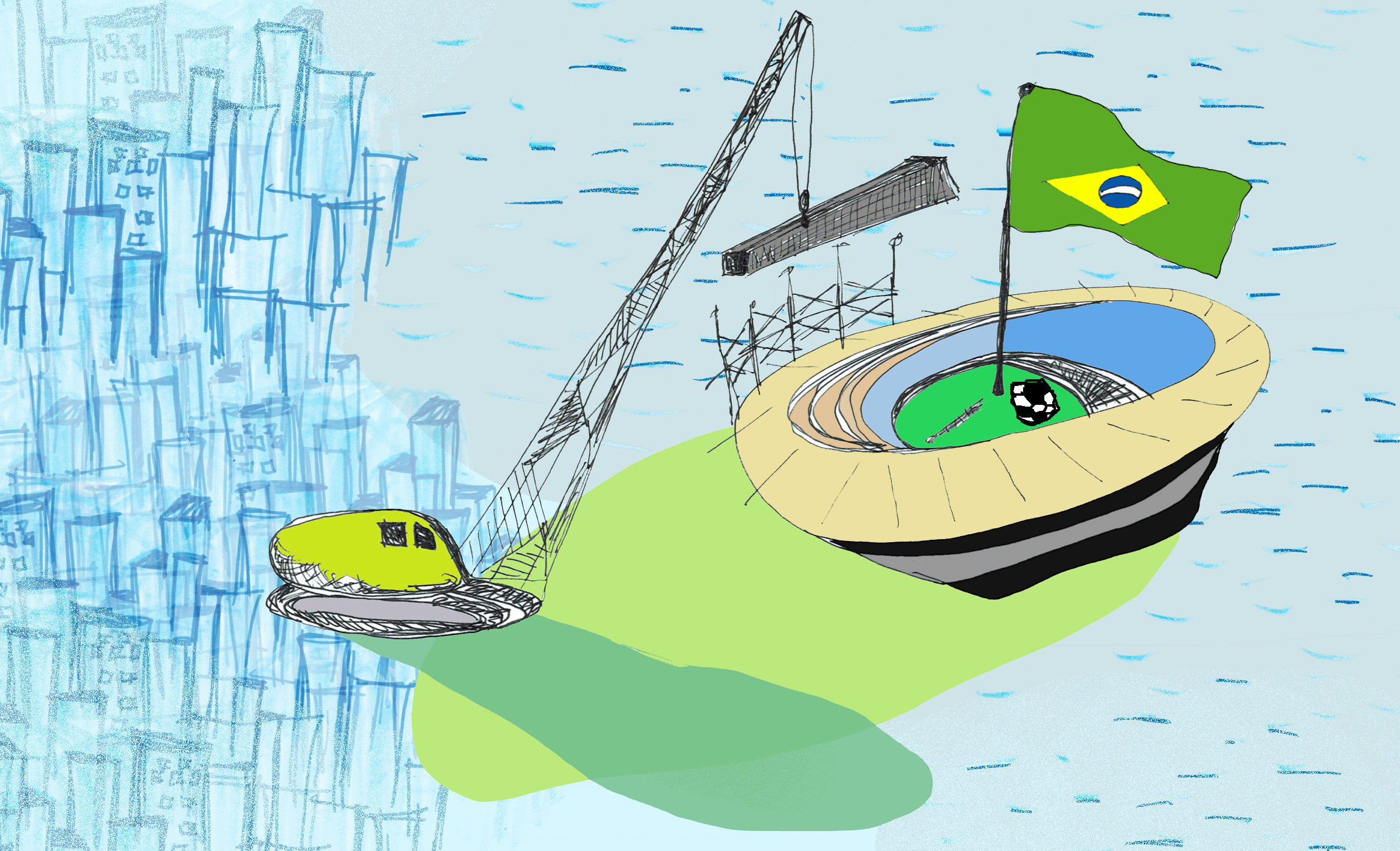

Soccer, beaches, carnival, scantily clad women. Clichés and stereotypes inevitably arise when talking about Brazil. Chief among them is the myth of the jeitinho brasileiro, or the “Brazilian way”: the informal and street-smart manner in which Brazilians live their lives. It is often said that every stereotype holds a grain of truth, but in the case of the jeitinho, a grain might be too modest a quantity.

The Brazilian way refers to the ever-present breezy attitude of Brazilians toward life, the way many deal with their problems by relying on charm, personal relationships and other shortcuts or quick fixes that make life easier. Can’t find a parking spot? Park illegally and give the parking enforcer a six-pack of beer on your return. Out of a job? Have your cousin who is the manager at the local supermarket hire you. Jeitinho has always been part of Brazil’s charm, but when it spreads to government — as it almost always does — it is a recipe for incompetence and corruption. Couple that with the responsibility of putting together the World Cup, and incompetence quickly escalates into disaster.

Ever since Brazil won the bid to host the 2014 World Cup in 2007, the country has been teaching the world a lesson on how not to prepare for a major international event. Mistakes were made right from the earliest stages of the planning process, beginning with the decision to have 12 host cities instead of a more manageable number. At the time of writing, only three of the 82 World Cup related projects were not over-budget or behind schedule. Two months before the Confederations Cup — the dress rehearsal for 2014 — three of the six stadiums scheduled to host games in the competition are still not ready.

None of this should come as a surprise. All that was needed was a look at Rio de Janeiro’s 2007 Pan-American games. The event’s main construction project, the Engenhão Olympic Stadium, was meant to cost $60 million Brazilian reais and scheduled to be completed in 18 months. In the end, the stadium cost R$380 million and took 54 months to be inaugurated — a mere two weeks before the start of the games. Adding insult to injury, the stadium was recently closed down due to structural irregularities. Its cover was rusting precariously, posing a serious risk to fans; it also presented electric and hydraulic problems. Botafogo F.R., the team that took over the stadium after the games, now considers returning it to the government, rendering it a white elephant in the heart of Brazil’s second-largest city.

The story is now taking place on a much larger scale. The culprit, as always, is the fatal mixture of corruption and bureaucratic stagnation that has long characterized Brazil. These characteristics are not unique to the country, but in Brazil incompetence is magnified by impunity and a lack of urgency, as well as a baseless faith that last minute improvisation is an acceptable solution to problems.

Take São Paulo’s Arena Corinthians, a stadium being built specifically for the Corinthians soccer club. When Brazil won the World Cup nomination, São Paulo seemed like the city best prepared to host the games, boasting three modern stadiums that would only require minor renovation for 2014. Defying logic, plans for a brand-new stadium were announced in late 2010. The stadium is being built in a remote and dangerous area of São Paulo, and due to the city’s notorious traffic jams it can take as long as two hours to reach by car. This pet project of former President Lula — a die-hard Corinthians fan — was set to host the opening game of the World Cup.

Progress takes place at snail’s pace and financing for the project is set to run out over the next few weeks. Corinthians still has yet to receive R$400 million in anticipated loans from state controlled banks. The problem is that Brazil’s development bank, BNDES, is forbidden by law to extend loans to soccer clubs and must do so through intermediaries like Banco do Brasil SA. Banco do Brasil is now the kink in this chain, refusing to release the funds in the belief that the collateral and guarantees for the loans — mainly ticket and naming rights revenue — are insufficient and lack specificity. The result is that Arena Corinthians may not be completed by the start of the tournament, leaving São Paulo out of the World Cup.

Similar problems are taking place throughout Brazil. One of the construction companies responsible for Arena Pantanal in Cuiaba quit in mid-March when the funding dried up. The company that took over is now scrambling to finish the stadium before the World Cup and will have to more than double its rate of progress to meet the deadline. Arena Pantanal will have a capacity for 43,000 spectators, even though Cuiaba is only home to a third-league team. It is destined to become another white elephant, along with stadiums in Brasilia, Natal and Manaus, the latter of which is home to a fourth league team. Combined, these four stadiums will cost over R$2 billion — yet the city of Belem do Para, home to one of Brazil’s biggest derbies, was inexplicably left out of the games.

Another problem is the ceaseless growth of budgets for stadiums. Originally budgeted at R$2.3 billion, the construction cost of the 12 stadiums has increased threefold. One can only assume that much of this money is going into the pockets of politicians and construction companies who often maintain cozy relationships with each other. An example is the construction company Delta, previously in charge of several World Cup projects, including the R$1 billion renovation of the legendary Maracanã Stadium in Rio de Janeiro. Delta, whose owner is a close associate of Rio Governor Sergio Cabral, became the subject of a congressional inquiry and was forced to forego its government contracts.

Scandal after scandal has exposed this collusion, to the point where the public has become apathetic. A poll taken in 2012 showed that 85 percent of Brazilians believed World Cup related corruption would be inevitable. Needless to say, transparency is almost nonexistent, with none of the 12 stadium projects adhering to a 2012 transparency law created for the World Cup.

Spending billions on stadiums in a country where many still have limited access to sanitation, health care and education is not easy to justify. Part of the expectation was that Brazilians would reap the benefits of much needed improvements in infrastructure, especially in the area of urban mobility. However, none of 50 urban mobility projects scheduled for 2012 were completed in time. The most ambitious ones have been abandoned, many have been scaled down and 19 are over-budget. Ongoing projects are mostly focused on access to stadiums, as opposed to solving the country’s overwhelming deficiencies in public transportation. Much of the incompletions and delays are due to mismanagement in government procurements, which were either too slow or awarded contracts to projects that were poorly planned or purposely vague. In the absence of concrete solutions, many host cities are now relying on quick fixes, such as decreeing municipal holidays on match day to keep commuters and students off the roads and creating temporary bus-only lanes to allow spectators to avoid traffic.

A final worrying factor is the state of Brazil’s airports, run by the inept government agency INFRAERO. In Rio’s Tom Jobim, Brazil’s busiest airport, electrical failures are commonplace, baggage conveyor belts break down regularly and waiting for hours to claim baggage is a normal occurrence. Considering 2014 will be one of the most well attended World Cups due to the international allure and excitement that Brazil generates, airports should have been priority number one on the list. But so far only 30 percent of the money earmarked for airport renovations has been spent. Service remains as slow as ever and the infrastructure shoddy. Now it seems that airports will not be renovated in time, and there is talk of temporary tents and warehouse terminals.

Despite the mistakes, scandals and delays, Brazilians don’t seem infuriated with the way preparations for 2014 are taking place. They’re not happy either, but they’ve become immune to this kind of behavior after decades of the same old story. Few in Brazil believe the country will ever reach the level of competency and efficiency of developed nations. In 2010, 60 Minutes interviewed then-President Lula for a special on Brazil’s rise. When asked about World Cup delays, Lula laughed them off: “You have to be careful about European perfectionism. Everything that happens here in the South, they think they know better than us…We will organize the most extraordinary World Cup ever,” he said, putting off the question with classic Brazilian jeitinho. Somehow “European perfectionism” has become a negative trait, too formal and rigid for the fun-loving, relaxed Brazilian lifestyle. Sadly, this mentality has increased Brazilians’ tolerance for corruption and incompetence.

Brazil has made progress over the past decade despite poor governance. Home to some of the world’s largest companies, its GDP per capita has nearly tripled while the country makes great strides against poverty. But Brazilians must learn when to shy away from jeitinho, overcome their apathy and demand more of their elected officials. Should this happen, it would be hard to stop the South American giant. But it can’t happen soon enough. The 2016 Olympics are just around the corner.

Joaquim Salles ’14 is a History and Political Science concentrator.

Art by Sheila Sitaram

An earlier version of this article contained the sentence “These characteristics are not unique to the country, but in Brazil incompetence is magnified by a lack of impunity and urgency….” The sentence should read, “These characteristics are not unique to the country, but in Brazil incompetence is magnified by impunity and a lack of urgency….” (emphasis added). The online version of the article has been updated to reflect this correction. Brown Political Review regrets the error.