Over the past few weeks I’ve written of change, in the United States and abroad. I’ve written of tarnished appearances, and put faith in the Kissinger realpolitik credence that image matters. Tattered domestic politics, I said, find consequences in the grand (and admittedly generalized) global scope of affairs. This week I want to continue that discussion, and I want to establish a comparison. After all, “History,” America’s favorite Mark Twain noted, “does not repeat itself, but it does rhyme.”

In July of 1956 Egyptian president Gamal Abdel Nasser nationalized the Suez Canal in response to the withdrawal of western funding for a proposed dam. During a speech he gave the night of the 16th, Nasser spoke a hidden code word, de Lesseps, the name of the 19th century French developer of the waterway. It was an instruction for Egyptian army officers to raid the office of the British Suez Canal Company and seize control of the canal. Though it took a few months, a tripartite force of the U.K., led by Prime Minister Anthony Eden, France, and Israel responded with force. The move was met with widespread opposition, both within Britain and around the world. America, perhaps hypocritically, also responded with indignation, no doubt fearful of what might happen to their image if they supported British intervention in Egypt while opposing Soviet intervention in Hungary.

What was most notable was the way in which America responded — by threatening to sell their British debt. What would have followed surely would have been disastrous. Harold Macmillan, then Chancellor of the Exchequer, reportedly told the British Cabinet that ”there had been a serious run on the pound,” noting ”that only a ceasefire by midnight would secure US support” in bolstering the pound sterling. The currency had never been in such dire straits, and it arguably never recovered. Such a move was a wily and immaculate form of economic diplomacy, and one that ultimately caused a retreat on behalf of the tripartite that November. Eden soon resigned as Prime Minister amidst a haze of accusations of misleading the British public and exceedingly low public approval. Macmillan replaced him.

What does all this have to do with present-day America? Perhaps little. But perhaps there is something to be said for the power of a single event, or a course of events, to turn a long-established economic order on its head. Many argue that the pound never recovered after the Suez Crisis. It is more accurate to argue that the Suez Crisis marked an end to the end for the pound, the finale to a process that began with Bretton-Woods in 1945. What is definitely true is that by the late 1950s, the U.S. dollar superseded the pound as the key global reserve currency in every aspect of the term.

Maybe this article is written too quickly on the whims of popular debate. It is all too easy to be an alarmist when everyone is pulling the alarm. But it does seem like confidence in the dollar, and in American debt, has never been lower (even if this has yet to play out in the markets). The Syrian crisis and the budget and debt ceiling fights proved that the institutions we so pride ourselves on, namely our Congress and our Executive, have hardly lived up their supposedly high standards. This was all voiced in a recent op-ed in China’s Xinhua Daily, provocatively titled “U.S. Fiscal Failure Warrants a de-Americanized World.” Keeping in mind, of course, that Xinhua is a state-owned paper, the op-ed joins a growing number of foreign writings lamenting U.S. policy (here’s to you, Mr. Putin). “Most recently,” the Xinhua editorial notes, “the cyclical stagnation in Washington for a viable bipartisan solution over a federal budget and an approval for raising debt ceiling has again left many nations’ tremendous dollar assets in jeopardy and the international community highly agonized…a new world order should be put in place, according to which all nations, big or small, poor or rich, can have their key interests respected and protected on an equal footing.”

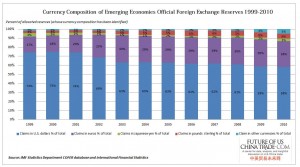

The piece is interesting on many levels, if one can for the moment leave aside the cynicism so often levied at the Chinese press. It is notable that it is being published in the first place, for while one might like to think of China as one giant propaganda machine, this is markedly pointed, outspoken criticism — if anything, a threat. It is also interesting in that it brings up a major question, one with vast future ramifications. What happens if dollar confidence declines? What if we no longer find ourselves as the go-to global reserve currency? Who would fill the gap? The Euro, surely, is too fragile. Major changes must happen to the European experiment were it to assume key currency status. That leaves the Chinese renminbi. The dominance of the sort the dollar enjoys certainly seems a long way off for the pegged note, but the future is often closer than it seems.

There is one other comparison to be drawn to the Suez Crisis, and it concerns an issue that has has seen some traction in popular debate. Could China use our debt as geopolitical leverage, just as we did with Britain’s? It’s a distinct possibility. Of course, China has as much to lose from their potentially perilous debt holdings as we do from our indebtedness. If there was to be a reduction in Chinese U.S. dollar holdings (and indeed the rate at which they are picking up dollars is slowing), then it would be a gradual one, I think, and not a dump as is so often feared. Nonetheless, it’s a threat, and a real one at that.

In 1956, the Suez Crisis marked the end of an empire. Britain’s intervention? The thrashing fits of a dying imperial power. Are recent events a harbinger of dark days to come for the dollar? It’s too easy to fall into the presumption of prediction. These are merely observations, both historical and present, that can hopefully illuminate some recent trends and events. What does seem certain is that nothing is certain — nations rise and fall, and as they do their currencies go with them.