Since the first Russian troops began invading Crimea, the West has considered various approaches to deter Russian aggression in Ukraine. For the United States and the European Union, focusing on diplomatic talks is a more effective strategy than the more punitive approach of escalating sanctions, providing weapons to the Poroshenko administration, or, at worst, putting boots on the ground in the war-torn “New Russia” region.

While some argue that Russian President Vladimir Putin will be pressured to retreat as a result of sanctions, these measures fail to consider that Putin is not primarily incentivized by economic means. In a New York Times opinion piece, Ben Judah writes, “Mr. Putin is not rational. Any rational leader would have reeled from the cost of Western sanctions. Russia’s economy is being hit hard by a credit crunch, capital flight, spiraling inflation and incipient recession. This will hurt Mr. Putin’s surging popularity at home. But none of this has deterred the smirking enigma.”

United Russia, Putin’s party, controls the Russian legislature, presidency, and executive branch, most of Russia’s media, and oversight of the electoral system. As 73 percent of Russians trust and use state media with respect to Crimea and Ukraine, there is no doubt that United Russia would frame consequences of sanctions as the West continuing to humiliate and assault Russia. In terms of his support base, it seems that Putin has little to fear from these sanctions.

Putin has never derived his legitimacy from being pro-Western, nor has he ever needed to do so. Regardless of his actual economic success, the Russian president’s enormous popularity comes from a well-established image as an economic reformer and fighter against rampant corruption caused in part by Western-led, IMF-supported failures at liberalization in the ’90s. Further sanctions and Western military aid to Ukraine will, if anything, strengthen his hold over the Russian majority. Putin is not irrational. He’s highly lucid and determined in dictating the policy of a country to which this conflict is extremely salient.

While Ukraine has indisputably borne the yoke of Russian imperialism, this does not mean a military approach from NATO will most effectively end the conflict given the nature of post-Soviet borders.

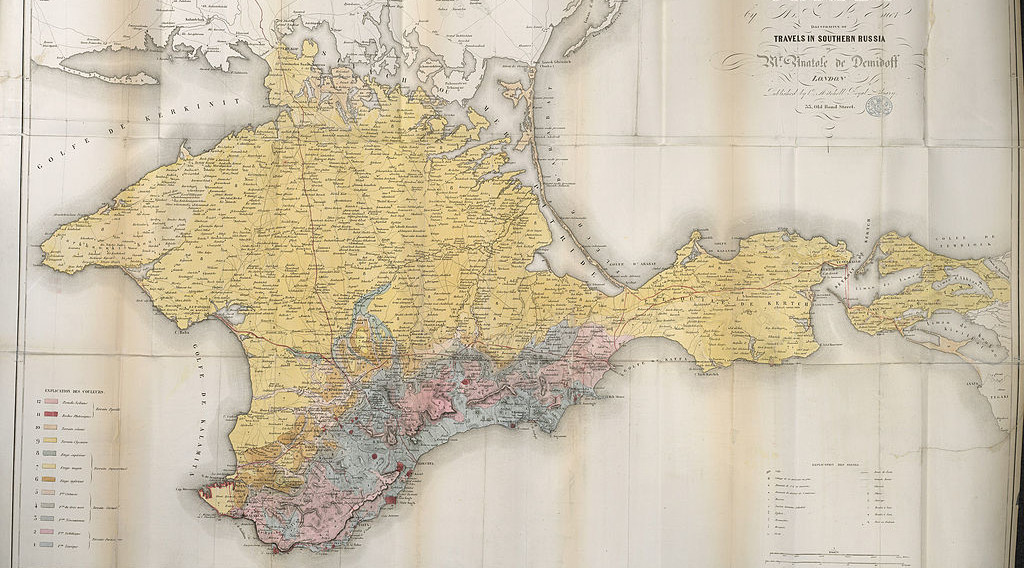

When the USSR fell, the independent states were divided along the borders of the Soviet republics. The boundaries between Soviet states, however, were not necessarily reflective of their ethno-national makeup. Sovietization, or the formation of a pan-Soviet citizenry with loyalty to Communist principles and Moscow administration, was a motivating factor behind shaping the structure of the country’s republics. Dating back to the 1920s with Stalin’s “Socialism in One Country” plan, the USSR sought to build “a country with a central state, a centralized economy, a definite territory and a monolithic party.” The goal was to create a unified Soviet people. So when Nikita Khrushchev ceded Crimea to Ukraine in 1954, he was merely rearranging borders to facilitate infrastructure management, according to his son, Sergei Khrushchev. The concept of the Soviet Union as a monolithic people still prevailed in terms of dictating top-down administrative policy.

Another Stalinist intent with the administrative borders was to divide and conquer indigenous populations. Issues of sovereignty over the Nagorno-Karabakh region between Armenia and Azerbaijan persist to this day, comparable to face-offs in Kyrgyzstan between Kyrgyz and the Uzbek minority. Another host to Soviet-exacerbated dispute is Ukraine, where a sizable amount of the population is Russian and identifies as such– this in particular concerns Crimea, a Russian-majority district, and the Donetsk City Municipality, which as of 2007 had a Russian plurality (48.15 percent).

The Russian-Ukrainian divide in terms of national consciousness is nothing clear-cut. There are key cultural entanglements between the countries. A BPR article titled “How to Forget Your Ex” described Russia’s imperial legacy and encroachment on the Ukrainian people. However, its description of Russia’s alleged co-optation of Ukrainian culture does not cover everything, for instance, regarding Russia’s “absorption” of Nikolai Gogol. Gogol may have been Ukrainian, but that did not stop him from actively being a fervent monarchist, nor did it stop his novel Dead Souls from waxing romantic about his beloved “Rus” moving forward as the nations of Europe watch in awe. Other influential writers such as Anna Akhmatova and Mikhail Bulgakov were Ukrainian-born yet definitively Russian in terms of ethnicity, language, and subject matter. If anything, this Ukrainian-Russian fusion indicates complicated, shared consciousness among many living within Ukraine’s borders.

The significance of this history is that former Soviet republics have borders that were made to break up local resistance to the Kremlin, not to provide paths for national self-determination. Civil war is inevitable as long as the borders of the Ukrainian state reflect the remnants of a Soviet-era divide-and-conquer strategy. The Russia-administered referendum in Crimea, as a matter of fact, probably reflects the loyalties of the Russian majority, even if the 96 percent margin of victory is likely exaggerated (given the Russian administration’s track record of winning elections by 140%). Russia’s decision to invade Crimea was an overt act of aggression, but its relatively peaceful result is hardly a pretext for installing NATO soldiers in Ukraine.

This is not an attempt to undermine the Ukrainian people’s right to their independence, nor is it to say that there is no distinct Ukrainian identity, culture or tradition. Rather, it is to say that there is indeed also a cultural and social history of Ukrainians expressly affiliating with Russia, and our understanding of the situation should incorporate these ties.

Simply put, the region’s complex history will not go away with US sanctions, military supplies or soldiers. These lengths would only add to the body count and further exacerbate the situation. Regardless of right and wrong, Russia sees Ukraine as an integral part of its national history, a blood brother.

One possibility is to negotiate as follows: the West allows Russia to keep Crimea. Then, agree to a new referendum in the Donbass region, to be monitored and overseen by Western officials, NGOs, and Russian officials with every possible effort at transparency. If at all feasible, this would allow for separatists’ voices to be heard, though not necessarily obeyed, in an affirmably democratic process. In exchange, Russia must recognize and respect all treaties Ukraine decides to make with the EU, NATO or other organizations.

Naïve though it may sound, if NATO, the US and the EU were willing to accept a few of Russia’s terms, while maintaining Ukraine’s right to its independence, we could ward off a regressive and simplistic Cold War mindset and minimize bloodshed.