The crisis in Ferguson, Missouri over the summer became another flashpoint in the debate about race in the United States. The controversy, like so many other recent incidents, revolved around the issues of racial profiling in police investigations and the injustices that stem from such discrimination. A less-explored part of the problems in Ferguson revolves around the lack of minority representation in government, a problem that is widespread and that permeates all levels of government. On the federal level, only 19 percent of representatives and 5 percent of senators in Congress are minorities, in a country that has a 36.3 percent minority population. The problem is especially potent, and less publicized, at the municipal level; Ferguson, for example, has a 67 percent black population, but a white mayor and only one black city council member. The example of Ferguson is unfortunately all too common, and the lack of representation questions the ability of government to respond adequately to the needs of all its constituents.

The race gap in local government is fairly common across the country. A study by the International City/County Management Association examined 340 American cities where the population is more than 20 percent black and found that 129 had city councils that were unrepresentative of the population. Most of the cities with an imbalance were located in the South, a region that has always struggled with racial issues. Conyers, Georgia is another fairly typical example: migration of African-Americans from Atlanta transformed the town’s demographics, but the local government looks very different from the people it serves. Only 21 of the city’s 170 employees are black, as is just one of six city-wide elected officials. The same narrative as in Conyers and Ferguson plays out in municipalities across the country.

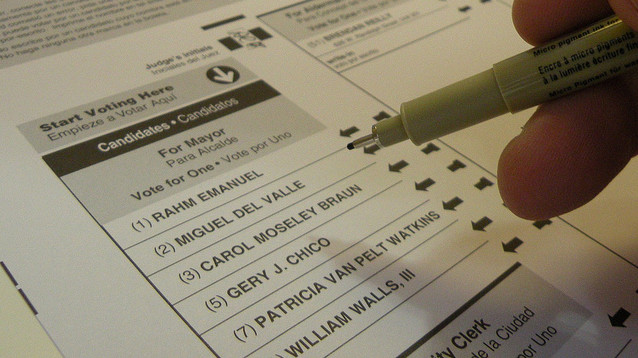

There are a variety of reasons for the disparity. Local elections simply are less publicized than national and state-level races, and consequently they draw far fewer voters. In 2011, average turnout in municipal elections was less than 21 percent. Even elections that capture national attention, such as New York City’s 2013 mayoral race, fail to escape the low-turnout trend. With such a low percentage of the population voting, the electorate is not representative of the whole community. Another pitfall is the nature of municipal offices: most require a fairly sizable time commitment but carry almost no compensation. As a result, often only affluent citizens can run for office.

Sometimes, however, the cause of the racial gap is more sinister; it’s no coincidence that most of the municipalities that exhibit it are located in the South. The same voting restrictions that affect national elections are at play in local races. In many ways the problem is worse at the lower level, since local issues receive far less attention. Section 4b of the Voting Rights Act outlined a formula that determined which jurisdictions would have to have voting changes approved by the Department of Justice. It was ruled unconstitutional in 2013 leaving many municipalities in the South free to change voting rules with little to no oversight. While the racial gap in local government is not always caused by discriminatory regulations, they do contribute to the problem, and it may only get worse with the recent changes in electoral law.

At the heart of the issue is the debate over the relative merits of descriptive and substantive representation. Descriptive representation is when elected officials resemble their constituents, and substantive representation is when representatives vote in the interest of their constituents while not necessarily existing in the same cultural, racial, religious or socioeconomic demographic. The racial gap may also exist simply because citizens feel their current representatives are adequately advancing their interests, and it is insulting to assume an African American voter will automatically vote for the African American candidate. Tim Scott, one of the Republican Senators from South Carolina, is African American, but his support for Republican policies alienates him from the interests of that community within the state. Still, having a representative government matters, and it’s clear that in many parts of the country that is not what voters are getting. In a country that still grapples with entrenched racial issues, having the most representative government possible is important. We still have a considerable way to go.