There were no newly constructed battle arenas, nor were there hordes of soldiers with unloaded guns. The war game that took place on October 13 between the United States and United Kingdom was a crisis simulation for the digital age: US Treasury Secretary Jack Lew and British Chancellor of the Exchequer George Osborne, along with the heads of both nations’ central banks, oversaw the financial war game. The exercise attempted to predict the fallout of a transatlantic bank failure and compare responses to avoid a repeat of the 2008 financial crisis. The conference, which has gained unwanted press as a puerile means of addressing deep-rooted issues, arrives in the midst of warnings from the International Monetary Fund about growing interest rates and inequality levels worldwide. Both governments have endorsed this game as a concrete way to remain prepared for future economic catastrophes. And while this seems like a drastic departure from the traditional image of the war game, there is in fact a strong precedent for computerized reproductions of disasters as a means of preparation.

War games usually refer to military drills or practices, often in times of imminent conflict. Nations regularly use such games as propaganda to publicly demonstrate their military power. However, as the scope of global crises evolves and expands, war games too have shifted to encompass a variety of catastrophic events. As well as economic war games, several of which have been conducted in the last decade, there have been attempts to test the response to terrorist attacks, cyber warfare and global pandemics. They are now being performed at an inter-governmental level, making them important factors in international relations.

These simulations are used as diplomatic tools to build diplomatic ties and foster cooperation between nations. The October 13 game allowed both nations to practice greater transparency in terms of prospective financial policy and promoted cross-national solutions to recessions. The same can be said of other, less theoretical inter-governmental war games: The United States regularly conducts war games with South Korea to solidify their strategic partnership in the face of North Korean hostility.

War games can also be surprisingly educational, predicting the unexpected outcomes of international relations. In 2012, for instance, the United States simulated a hypothetical conflict between Israel and Iran during a period of significant antagonism between the long-time regional rivals. The scenario was run in the wake of an Israeli attack on Iran’s nuclear program, an inauspicious if topical context in which to run the simulation. The mock-up had Iran retaliate against Israel while also firing missiles at an American battleship. The game, which lasted two weeks, predicted that the isolated battle would morph into a long-term war that would have dire consequences for the American military. It alerted planners in Washington as to possible threats and gave credence to those in Congress who would prefer to distance themselves from further Middle Eastern conflicts.

War games, however, are more often used to threaten other nations, undermining regional stability rather than strengthening peace. China in particular is a pioneer of this tactic, using war games to demonstrate their regional supremacy in periods of tension. In July, following disputes with Japan over the Senkaku Islands, the Chinese government held air force drills near the border with Japan. Russia, too, has a history of using war games to intimidate their neighbours; in 2009, less than a year after their war with Georgia, they held large military drills near the Georgian border to illustrate their ability to continue the war. Earlier this year, Russia and China took part in joint military exercises in the Mediterranean. The development of this new, Eurasian security vector was a source of concern for the American government, particularly in the light of Russia and China’s joint support of the Assad regime in Syria.

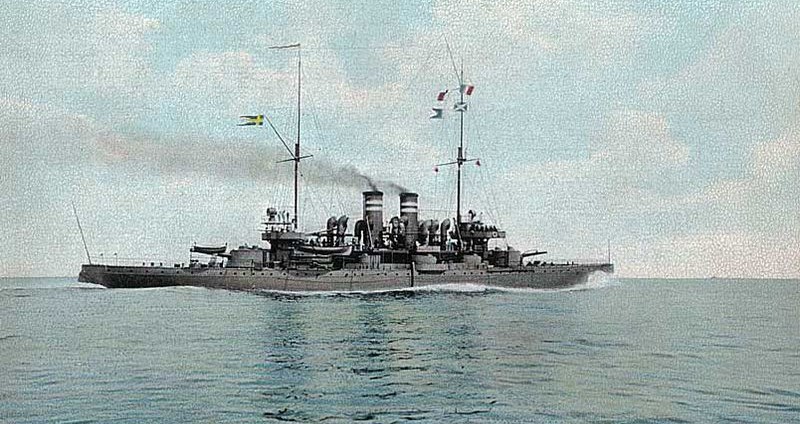

Similarly, and perhaps more famously, Iran is notorious for their use of military drills to irritate their western rivals. In 2012, they held a provocative naval simulation near the Strait of Hormuz. Though the simulation itself was fairly routine, it was held unusually close to key Gulf oil shipping lanes. By organizing war games in such a location, they illustrated a measure of predominance over international waters, establishing their strategic influence in regional, and global, affairs.

The United States, too, is guilty of using war games as lightly camouflaged displays of force. They have just emerged from a series of war games with Latvia, recreating a “Stalingrad-type scenario” with urban battles against a strong paramilitary force. Given the Russian invasion of Crimea and their subsequent hostility with the United States, this reiterates the American support for Russia’s neighbours and undermines Russian regional hegemony. The American military also performed a series of war games with their counterparts in the Philippines earlier this year. This was particularly significant as it occurred amidst the territorial disputes between the Philippines and China; though the games focused on combating piracy and natural disasters, it also underlined the American commitment to the Philippines and their strong presence in the region. Similarly, during Japan’s dispute with China over the Senkaku Islands, the American and Japanese governments held conspicuous, large-scale military simulations in the Pacific. While they claimed that the games were routine, and had been planned years in advance, the message to China was clear: We’re still here.

However, despite their obvious significance to international politics, these simulated recreations are often criticized for being meaningless at preventing crises. This became especially evident in March of this year, during a nuclear summit involving Obama, Xi Jinping, Angela Merkel and David Cameron. Obama sponsored a surprise nuclear war game replicating a terrorist attack with nuclear weapons. German Chancellor Merkel was apparently disgruntled at having to take part in the exercise, and her criticism is certainly well founded. For example, the simulated terrorist attack of the London transportation system in 2003 was not enough to prevent the parallel July 7 terrorist attacks that wreaked havoc in the city. More frustrating was the British government’s failure to predict the credit crunch in August 2007 after “role-playing” an identical crisis in 2004. The financial war game underlined the vulnerability of banking institutions Northern Rock and HBOS; subsequently Northern Rock went into public ownership, while HBOS was the subject of an emergency takeover and government bailout.

But perhaps the most incredible example of the failure of war games is the simulation conducted by the American government in 1999, recreating an attempt to overthrow Saddam Hussein. Reports show that the Desert Crossing war game predicted the post-invasion political instability and ethnic fragmentation. It also predicted “widespread bloodshed” when rival factions competed for dominance, proving to be omniscient about the fallout of the war. Thus, the ‘success’ of war games is ultimately futile so long as governments disregard their findings.

In general, it is hard to deny that war games are becoming an increasingly relevant part of international relations. They are used as both diplomatic tools and disguised aggression, simultaneously solidifying alliances and intimidating rivals. However, it is naive to think that they can provide solutions to military, terrorist or economic crises. Ultimately, they may prepare nations but more often than not, they fail to protect them.