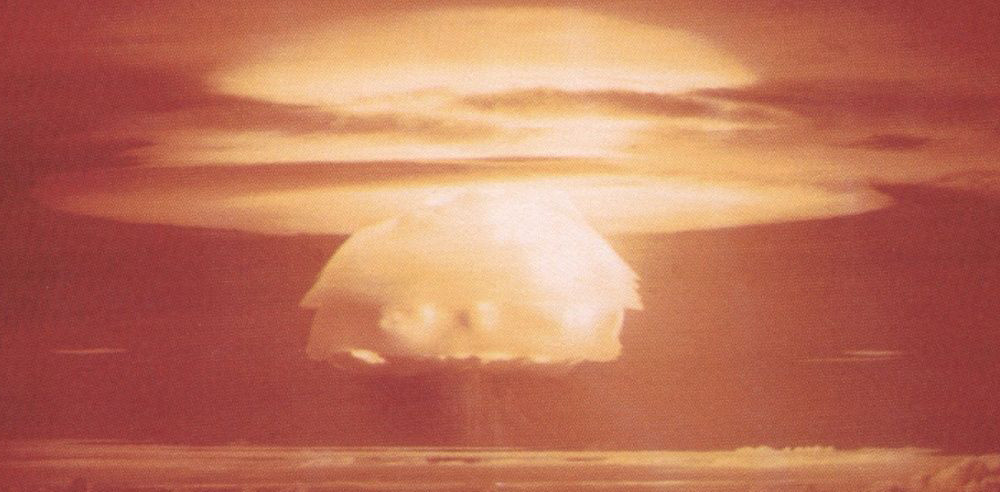

A national Pakistani hero, for whom more than a dozen academic institutions have already been named, spent five years under house arrest — albeit in a mansion with a rambling driveway crowned by a jasmine bush carved into the delicate shape of a mushroom cloud. Abdul Qadeer Khan (usually referred to as AQ Khan) is considered the father of Pakistan’s nuclear program and, in Pakistan, is celebrated for his role in bringing the country to the forefront of global politics.

But in the rest of the world, views on Khan are not quite so friendly. Former CIA director George Tenet once called him “at least as dangerous as Osama bin Laden,” and he’s been described as anything from “reckless and egotistical” to “the merchant of menace” to “the most dangerous man in the world.” His ascribed motivations have ranged from nationalism to fanatical Islam to simply greed. But beyond his personal motivations, AQ Khan’s success indicates that the movement of nuclear technology is not easily controlled, and introduces the possibility that his black market shenanigans might one day be repeated.

The story of Khan begins in the West, perhaps contrary to popular impressions. The son of an Indian schoolteacher and later educated as a metallurgist in Germany and Belgium, Khan studied nuclear energy in Europe before bringing secret blueprints for a weapons-grade uranium centrifuge to Pakistan from the Netherlands. Although there are disputes about whether the designs were stolen — a Dutch court convicted AQ Khan of industrial espionage in 1983, but a technicality meant that the conviction was later overturned — they were essential to the Pakistan Atomic Energy Commission and were the basis for the country’s first enrichment project. Even more confusing is that the United States knew what was going on — State Department documents show knowledge that the reactor plans had been stolen, but the United States never made moves to curtail Pakistani nuclear ambitions.

AQ Khan then led the Khan Research Laboratories (KRL), whose uranium enrichment program was directly responsible for the first nuclear test of a Pakistani weapon in 1998 — an era during which the United States was providing billions to the country in aid. Today, the Pakistani army has approximately 50 nuclear warheads under its belt, largely thanks to Khan. But it isn’t for his role in Pakistan’s nuclear weapons development program that AQ Khan has gained his worldwide infamy — it was his sales, or offers of them, of nuclear technology to all three countries in Bush’s axis of evil as well as to Libya (which spent more than $100 million buying nuclear goodies from Khan’s syndicate) and Syria: countries whose instabilities have been especially salient in recent news cycles.

The assistance that Khan gave was powerful. Khan’s network provided North Korea with almost all of the components of its current stockpile, including its high-speed centrifuges and its bomb designs. Importantly, North Korea sought out the assistance to its program after the United States had stepped in to curb North Korea’s nuclear enthusiasm by freezing its plutonium production. Khan was just a way around. Pakistan also helped Pyongyang with missile development, meaning it isn’t just the warheads, but also their carriers, that can be traced back to scientists in the Middle East.

In the 1990s — a critical time for Iranian nuclear development — members of Iran’s nuclear program met with members of Khan’s network at least 13 times. The consequences of Khan’s actions are not light: Iranian and North Korean nuclear developments have been at the heart of international politics and will likely continue to have an important role in discussions of global security. Khan and his researchers also published scientific papers containing detailed information about nuclear weapons; while not providing the full story, Khan’s work makes it much easier for states to design new nuclear plants. This likely was the motivation behind the papers in the first place; Khan remarked in one that his aim was to whisk away “the clouds of so-called secrecy.”

In 2000, the international intelligence community began finding and compiling evidence regarding AQ Khan’s under-the-table dealings routed through more than 100 suppliers. As it became increasingly evident that AQ Khan had become the head of a large, underground nuclear technology distribution network, the United States increased pressure on Pakistani President Pervez Musharraf to intervene in Khan’s affairs. By 2001, Khan had been removed from his position at KRL, and instead was made an advisor to the Musharraf administration — a move justified to the United States by claims that he would be under tighter government suspicion in his new role. The action angered Pakistanis, who viewed the intrusion by the United States into their domestic affairs and into the life of one of their national heroes as just that: an unwanted and unwarranted intrusion.

Despite Khan’s removal, his proliferation ring did not end with his job at KRL. In 2003, a vessel carrying centrifuge parts was found traveling to Libya, and AQ Khan was suspected of being the instigator of the foul play. Subsequently, the United States stepped in to seriously consider the evidence regarding Khan’s affairs and placed sanctions on the KRL. After its investigation, the United States concluded in 2004 that Khan’s black market contacts had been used for the distribution of nuclear information and materials to at least Libya, Iran and North Korea, and that he had access to an extensive and elusive network of suppliers across the globe.

After Khan’s confession in 2004, he was placed under house arrest but never actually charged with a crime. Five years later, an official pardon by the Pakistani administration made Khan a free man again — and again a rich one at that. Given his status as a multimillionaire with an impressive collection of mansions and vintage cars, it seems that the smuggling industry did Khan quite a bit of personal good.

Unfortunately, it’s unlikely that Khan reformed during his years on house arrest. In his first interview with Western media since being pardoned, Khan dismissed his earlier confession, saying that he had not made it “of [his] own free will.” Khan also still insists that he’s innocent; because Pakistan is not a signatory to the Nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty (NPT), Khan says that he did not, technically, violate any binding international laws, although that claim is complicated at best. The atomic scientist has also dismissed journalism about him as “shit piles” and been openly hostile to Western governments in his rare media appearances, once even commenting: “all Western countries are not only the enemies of Pakistan, but also of Islam.”

Although the Pakistani government claimed that it had played no part in the proliferation activities (Musharraf remarked in his memoir that after learning Khan was “up to mischief,” he immediately removed him from his post), Khan’s former dubious activities raise a number of serious concerns regarding whether a senior official could really have distributed top-secret technology to foreign governments without higher approval. If Pakistan’s highest authorities were involved, the lying implicit in the affair is notably problematic. If they weren’t, the incident demonstrates a severe lack of accountability measures and suggests that the scenario could happen again, and again go unnoticed. Either way, the government must have been involved on some level, because it — and not just Khan’s laboratory — was responsible for an ad in 2000 for exports of nuclear equipment with the note that the technology “would be useful in a nuclear weapons program.”

Concerns about nuclear safety in Pakistan are no small situation. Taliban and al-Qaeda influence mean there are several operatives working within Pakistani borders. Although the Taliban has not expressed a direct desire to acquire a nuclear capability, the United States has been worried about the possibility of Taliban control of Pakistani weapons for decades, and al-Qaeda has explicitly stated that the acquisition of nuclear weapons is one of their major goals. Pakistan has also already been implicated in nuclear terrorism; in 2001, two retired Pakistani nuclear engineers met with Osama bin Ladin and Ayman al-Zawahiri in Afghanistan to discuss nuclear weapons. While the two weren’t specifically connected to Khan — and there’s no concrete information to suggest that Khan did business directly with al-Qaeda — several members of the Pakistani intelligence and military communities with known al-Qaeda sympathies are also known to have worked with Khan and his network during the peak of their operation.

Beyond the risks of nuclear terrorism, the incident also demonstrates the sophistication of smuggling networks and a major failure of international intelligence; Khan admitted to illegitimate proliferation activities from 1989 to 2000 (although his network’s activities actually continued beyond 2000), but it nevertheless took more than a decade for sufficient suspicions to arise and shut down the smuggling. In fact, Dutch intelligence had been watching Khan since the 1970s, as had the CIA, but both were unable to gather enough evidence for any sort of conviction. This is a fact that demonstrates both the complexities of combatting nuclear terrorism in today’s globalized economy and the shocking ease with which smuggling — even of something so unusual as nuclear materials — can be covered up. The intelligence failures have been attributed to poor coordination, outdated Cold War era reconnaissance techniques and even the secession of US administrations. Each with different intelligence priorities, the mechanism of the failure is less important than the lesson: the world can miss something even as major as the development of weapons-of-mass destruction.

In Iraq’s case, this proved particularly true. Not only did US reconnaissance miss the boat on AQ Khan’s connections to Saddam Hussein, but it also missed the development of Iraqi WMDs entirely — not in 2001, but in the 1990s, when Iraq stepped up development of their nuclear weapons program before the Gulf War. Iraq isn’t the only country that’s tried to build bombs in secret, and it won’t be the last; if the global community is going to cut off proliferation efforts before they get serious, stepping up monitoring is of critical importance.

The Khan events also reveal important limitations of the current global nonproliferation system and its seminal document, the NPT. Although designed to restrict nuclear weapons development across the globe through a number of regulations on trade and behavior, the NPT came with a bargain: a commitment from the nuclear states to provide non-military nuclear assistance to the rest of the world. As a result, the dispersion of dual-use nuclear technology — rhetorically for civilian use, but often ultimately for military use — has been an important facet of the spread of the bomb. And the NPT’s other clauses have been ineffective against this menace. Furthermore, three nuclear states — Pakistan, Israel and India — aren’t even signatories to the document.

Although only a scattered handful of nine countries actually have a weaponized nuclear capability, at least thirty have, at one point, pursued a nuclear capability. Such states range from Argentina and Algeria to Finland and Taiwan. The risks of proliferation are, in some sense, self-evident: Theorists — at least a prominent group of them — see more weapons as more chances for war, nuclear terrorism or belligerent diplomacy. That’s why Khan’s work is more than just a story of one corrupt man.

Khan is remarkable for being one man that managed to cause a megaton of chaos across the globe — and the story is even more shocking for the fact that he may have done so just for the money. The activities of Khan’s network raise major questions for the modern age about the effectiveness of global intelligence, the inevitability of nuclear proliferation, the likelihood of nuclear terrorism and even the risk of a repeat incident. As the nuclear club grows, how the world will continue to monitor who has access to nuclear technology will be a seminal question for global security.

This piece is part of BPR’s special feature on terrorism. You can explore the special feature here.