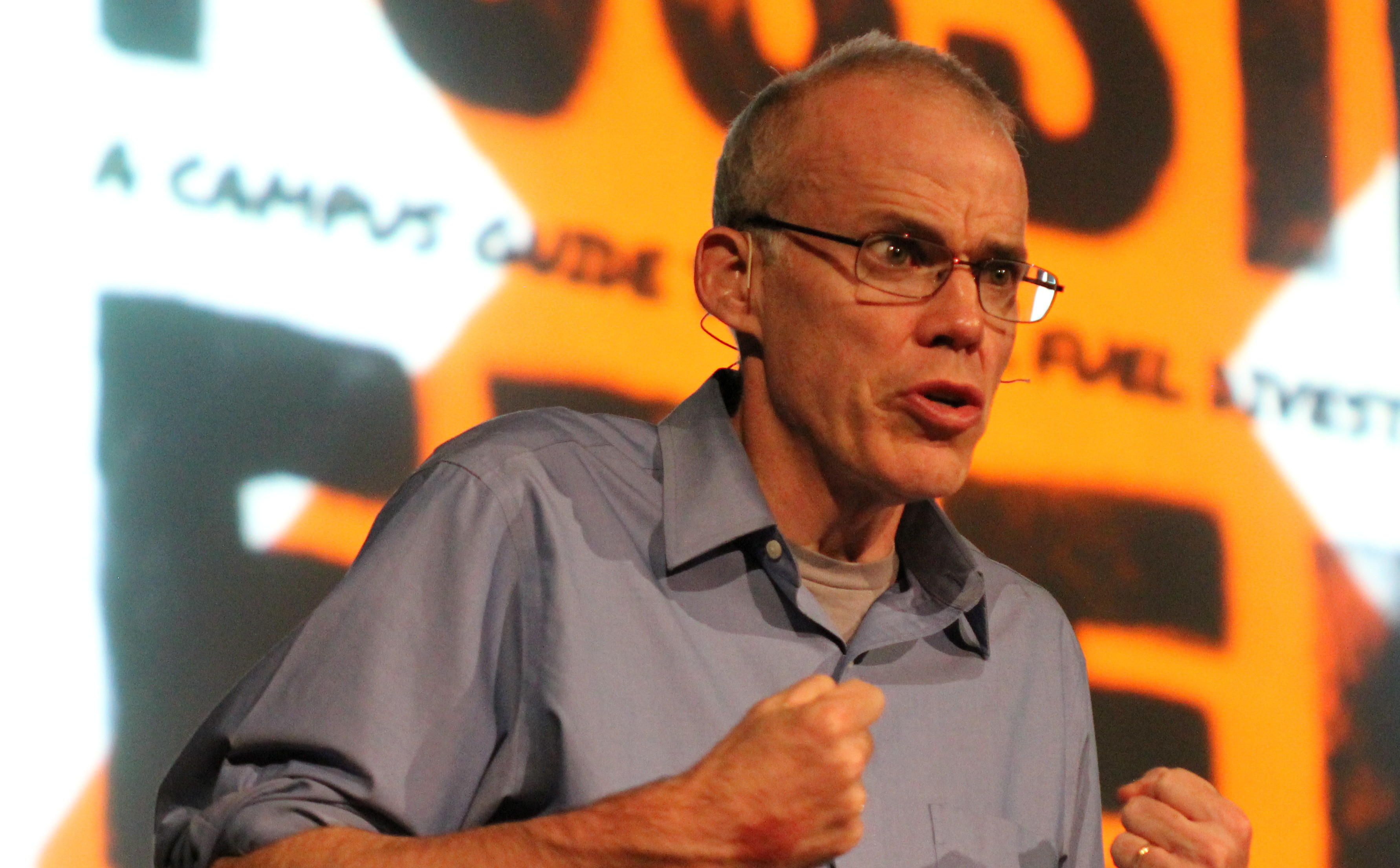

Bill McKibben is the author of “The End of Nature,” widely regarded as the first book about climate change written for a general audience. He is a founder of 350.org, the first global grassroots climate change movement. The Schumann Distinguished Scholar in Environmental Studies at Middlebury College, he was the 2013 winner of the Gandhi Prize and the Thomas Merton Award.

Brown Political Review: How would you characterize President Obama’s legacy on climate issues?

Bill McKibben: It’s extraordinarily mixed. On one hand, he’s done more than his predecessor, Mr. Bush, but I’ve drunk more beer than my 14-year-old niece — that’s not a very high bar. He’s also done an enormous amount to open up vast swaths of America for more oil and gas drilling; in his tenure, the United States has passed Saudi Arabia and Russia as the biggest hydrocarbon producer on Earth. He’s also raised gas mileage for cars, which is good. It’s up, down, up, down.

BPR: The United States recently reached a deal with China to curb emissions. Is this significant beyond communicating to the international community a willingness to proactively address climate change?

BM: It’s less a deal than a kind of pledge — a pledge written on someone else’s credibility. Since it’s not a treaty approved by the Senate, [the agreement’s] significance entirely depends on the next three presidents deciding to follow it. The way that the United States and others have set up the current round of negotiations, they’re all about these voluntary promises and commitments. That said, it was a useful thing to get the Chinese to acknowledge that the day will come when they have to use less carbon.

BPR: Regarding the upcoming UN climate talks in December, do you think there is a potential for impact?

BM: The mistake that observers and environmentalists have made over the years is to imagine that the real action is going on in these kinds of forums. It’s not. These ratify, or don’t, what’s happening in the real world, and what’s happening in the real world is a constant fight for supremacy between the fossil fuel industry and those of us opposed to it. At this point, pretty much everyone has agreed on the basic analysis that the fossil fuel industry has, in its reserves, about four or five times as much carbon as scientists think we could safely burn. The question is, will they have enough political weight to dig up all those reserves, burn them and keep their business model another decade or two at the expense of wrecking the planet over geologic time? Or will the rest of us manage to head them off? Stay tuned.

BPR: Where do you think momentum should come from for the global climate activism movement?

BM: A ton of the momentum has come from people on what one might call the “advanced lines” of dealing with the fossil fuel industry. Mostly it’s people in particular places having to deal with particular problems. The architecture is different from great movements of the past when there was a great leader or a few great leaders, or like the great television networks of the past, where there were only a few places messages were coming from. This is more like the Internet. There are a zillion locations of significance and that’s good news because the fossil fuel industry itself is very sprawling and protean, so one has to be protean in order to stand up to it.

BPR: At the People’s Climate March, “system change not climate change” was a common rallying cry; it seemed like there was a focus on the economy as a potential locus of change. Do you see a causal relationship between the logic of capitalism and the results of climate change?

BM: The kind of capitalism we’ve been practicing lately fetishizes the idea that you should be allowed to do anything you want if you have a lot of money. It isn’t working out very well. Carbon dioxide pollution is a classic example of why completely unregulated markets can’t solve problems. Since we’ve made sure that carbon carries no price, markets are innocent of it. If carbon carried a price, markets might provide part of the helpful response. Remember, the biggest spokesmen for libertarian, unregulated capitalism in this country are the Koch brothers. They’re also the biggest leaseholders in the tar sands of Canada. They’ve also made more money off oil and gas than any other people on Earth. It’s working well for them; it’s not working for the other seven billion people on the planet…I think the most important thing that happened in the last few hundred years was the development of fossil fuel. I think it was more important than the development of ideology. It’s no accident that it wasn’t until after the invention of the steam engine that Adam Smith wrote “The Wealth of Nations,” not the other way around. When we take action to deal with climate change, we’re probably going to be making changes to the way that power and wealth are spread around this world. I don’t see any way that a world that runs on sun and wind, which are omnipresent but diffuse, won’t have a different balance of power than a world that runs on a few pockets of coal and gas and oil that happen to be owned by the people sitting on top of them.

BPR: What incentives are there to act on climate change?

BM: The main incentive for the fossil fuel industry is going to have to be the realization that their current way of business isn’t going to work. And until we’ve been able to convince them that they’re not going to be able to dig up their huge reserves and burn them, they’ll keep doing what they’re doing. It’s a political fight.

BPR: Do you have anything to say in particular to a college audience?

BM: Only that it is a great shame that Brown University, so far, has not divested from fossil fuel. One would think that Brown, with its own particular history of where its money came from, would be particularly acute to thinking about being on the right side of history. But that said, I have no doubt that eventually it will do the right thing because it is such a wonderful place.