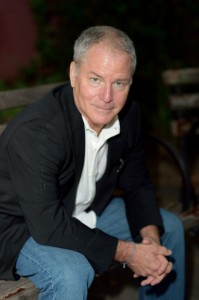

Larry Siems, the author of The Torture Report, is a writer and human rights activist. He is the editor of the New York Times bestseller “Guantánamo Diary,” the memoir of Mohamedou Ould Slahi, who has been imprisoned at the Guantánamo Bay detention facility since 2002.

Larry Siems, the author of The Torture Report, is a writer and human rights activist. He is the editor of the New York Times bestseller “Guantánamo Diary,” the memoir of Mohamedou Ould Slahi, who has been imprisoned at the Guantánamo Bay detention facility since 2002.

Brown Political Review: Describe the scope and magnitude of the “Guantánamo Diary” project.

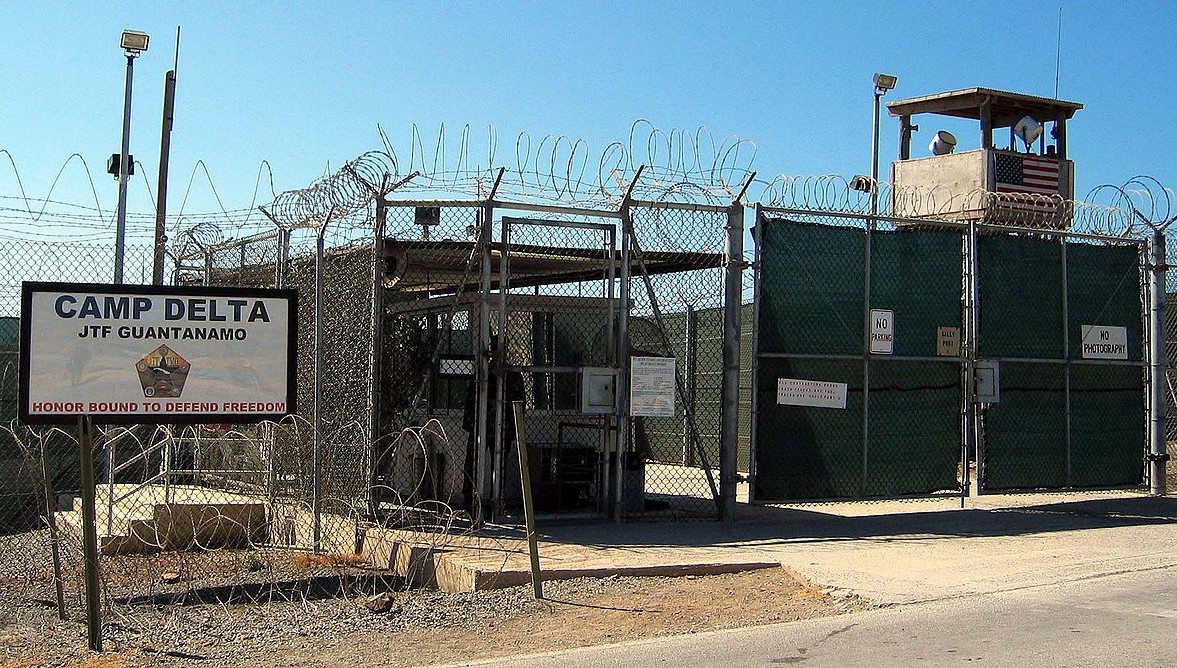

Larry Siems: It’s an incredibly unique project because it’s the only manuscript that’s made it out of Guantánamo. Mohamedou wrote “Guantánamo Diary” in 2005 in an isolation cell that he had been dragged into as part of this extremely brutal so-called “special projects interrogation.” He began writing in the spring of 2005, when he found out he would finally be allowed to meet with attorneys. With their encouragement, he continued to write through the summer and in September finished the 466-page handwritten manuscript in English, his fourth language. But like all materials that are produced by Guantánamo detainees, the manuscript was deemed classified from the minute it was created, so it was removed from Guantánamo and kept in a locked facility outside of Washington DC. For about six and a half years, his attorneys conducted litigation and negotiations behind the scenes to get the manuscript through two stages of clearance: declassification and clearing for public release. They finally achieved that in the summer of 2012. The previous four years I’d been working on a project called “The Torture Report” with the American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU). The ACLU had managed to extract about 140,000 pages of formerly classified government documents from the Department of Defense, the Department of Justice, and the CIA that documented prisoner abuse in Guantánamo, Afghanistan, Iraq and the CIA black sites. My job was to go through these documents and piece together narratives. Mohamedou’s story was one that really stood out, as one of two “special projects interrogations” in Guantánamo he was subjected to extremely brutal torture that lasted from 2003 into 2004. By 2012, I knew that his story would be remarkable: an epic journey through America’s post-9/11 national security, global gulag, covering about 20,000 miles with interrogations in five different countries. What I didn’t know until I got the manuscript was what an incredible writer and what a humane and eloquent conveyor of experience Mohamedou is.

BPR: How did you approach editing Mohamedou’s manuscript?

LS: I was dealing with a manuscript by a living writer who was completely inaccessible to me. I was especially committed to following his voice and what I felt to be the direction and intent of the manuscript. What’s remarkable about this book is that it’s a voice from the void – [one that’s] resonant, accessible, wise, funny, empathetic and ultimately forgiving.

BPR: American politicians and bureaucrats have couched the torture discourse in a vocabulary that abstracts away from its human consequences. How does the “voice from the void” undermine that legalese?

LS: It’s a voice that insists on the humanity of the speaker. You can see a humorous, creative, perceptive, feeling individual. There’s a sensual core to the story. Mohamedou’s two essential characteristics are empathy and curiosity, which are among the most universal and compelling human characteristics. There’s this amazing scene where [the detainees are being] delivered to Guantánamo in a freezing cold airplane. The guards are yelling at them, “sit down, shut up, cross your legs.” One guard yells: “do not talk,” and another yells: “no talking.” In the extremity of that situation and the pain and the fear of that moment, he says, “I noticed that they have two different ways of giving the same order. That’s interesting.” He begins a process of reclaiming the humanity that this entire system was set up to deny or negate.

BPR: The “voice from the void” reached the public a month after the release of the Senate Select Committee on Intelligence’s report on the CIA’s torture campaign. How does Mohamedou’s memoir complement the report?

LS: The torture report gave us a real sense of the magnitude of the brutality of the torture regime carried out under US authority after 9/11. For the first time they list the names of several dozen innocent people held in CIA black sites. The report hints at the human side of these things, and then Mohamedou’s book comes along, and for the first time tells what it means to experience this sort of treatment. Not just for him, but also for those who are in the position of meting out these illegal policies.

Guantánamo was born in secrecy, secrecy that was designed so that torture could happen and perpetuated to conceal the fact that it happened. Institutional secrecy now exists to delay accountability. It took the Senate Intelligence Committee two years just to get the executive summary of their report declassified.

But culturally we’ve also drawn a curtain in our minds around these places. We haven’t done much to tear down the secrecy because we’re afraid of what we’ll find. Mohamedou pulls back that curtain for us and allows us to see and experience this world in all of its pain and dehumanizing brutality. But he also shows us that even in the face of such relentless dehumanization, it’s a place of real human exchanges: occasional gestures of kindness and warmth, identification, recognition, sometimes even forgiveness, redemption.

Under international law, violations of the convention on torture require two things: investigation of the torturers and restitution for the victims. An essential part of that restitution is the process of recognizing the experience of the victims of torture and of the torturers. As this book makes clear, torture damages not just the tortured prisoner but also the captors who torture. It reveals the cost of these things on a human level, for everyone.

BPR: The media response to the Senate’s report distracted away from that human cost: waterboarding, sexual abuse, forced rectal feeding. The question the media posed was, did the United States gain “actionable intelligence” from “advanced interrogation techniques”? Was that question of efficacy raised to carve out a context of justification for such “techniques”?

LS: The Senate Intelligence Committee report foregrounded the [media’s] question. In fact, that’s specifically what they set out to study. The US government’s position was: First, we’re not torturing. Then, when information came out about advanced interrogation, it was the legalese saying: “This isn’t torture.” Finally, it shifted towards: “The gloves came off and we beat some people up, but we did it because we had to get crucial information.” The whole moral argument against torture seemed to have failed, so I think the Senate Intelligence Committee tried to address the efficacy argument. When you take that approach…you end up deflecting attention from the fact that torture is deeply immoral according to our understanding of human rights and dignity and that it’s forbidden under international and domestic law. It was a red herring to focus on efficacy, but I think that was one of the sustaining bits of scaffolding in the public imagination about the question of torture. Polling reveals a distressing trend whereby more people in 2014 accept torture as a necessary and efficacious part of counterterrorism than in 2002. Something has happened in the public consciousness that has allowed that tacit approval to grow. The efficacy argument has taken root. There’s also popular culture and the way that torture is depicted in mass media. From 24 to Zero Dark Thirty, there’s this plot device that assumes [torture] produces information. The Senate Intelligence Committee report is a devastating deconstruction of [that public perception] and shreds the idea that this was an effective program. It begins the process that Mohamedou continues in his book: refocusing the attention on individuals.

“Mohamedou pulls back that curtain for us and allows us to see and experience this world in all of its pain and dehumanizing brutality. But he also shows us that even in the face of such relentless dehumanization, it’s a place of real human exchanges.”

BPR: Does that process speak to a broader relationship between literature and cultural memory?

LS: Absolutely. Literature is an essential part of the process of cultural reflection and of moving things from the bureaucratic language of documents to the larger question of, “How did we get to this point?” That’s always a question of we, not they. Literature widens the circle of implication. How much are we responsible for these things and for moving forward and taking responsibility for ourselves so that they don’t happen again? That’s the critical part of the torture debate that we haven’t had yet. We’ve had this struggle for nearly 14 years, about accountability for the torture that happened under US auspices after 9/11. So far, those who designed and carried out [the programs] have controlled the narrative. That control is sipping away. We’re going to start hearing more voices like Mohamedou’s. He has broken ground in the most beautiful, undeniable and eloquent way.

BPR: If you read “Guantánamo Diary” alongside the Senate report, what gaps in the story are still missing?

LS: The stories of the guards and the interrogators, who had to carry out these programs and who are also bound by the secrecy regime. There are thousands of them living among us now and carrying the burden of conscience for the things that we’ve done. I think that there are people involved in Mohamedou’s case who would love to talk publically about what their experiences meant to them. They bear the burden of conscience for a culture that has in some ways asked them to do these things. Yet we have not acknowledged their stories, or begun to reckon with what it meant to put them in these positions.

BPR: Do you think those stories will ever be told?

LS: Yes. Mohamedou’s book is both a driver and a symptom of a shift that we’re beginning to see. You can’t sweep these things under the rug. They’re literally imprinted on the bodies and in the minds of people around the world. The Senate torture report, Mohamedou’s book — we can choose not to talk about these things. But make no mistake: the world is talking about them. We serve no national security purpose by trying to suppress this information because it’s already out there. The real national security question that’s looming is whether we’re capable of confronting the information.

BPR: In his State of the Union address President Obama reiterated his promise to close Guantánamo. But in 2010 his administration appealed a US District Court judge’s decision to grant Mohamedou’s habeas corpus petition. With his case in legal limbo, Mohamedou remains imprisoned. How do you explain this contradiction on the part of the administration?

LS: The administration could withdraw its objections to the habeas ruling and Mohamedou could be released. That hasn’t happened. It goes to the heart of our national contradiction about these questions, which is completely unresolved. Why hasn’t Obama closed Guantánamo? He said he would. I sincerely believe he wants to. So why hasn’t he? Resistance from Congress. Then the question becomes, why does Congress keep doing this? If Congress explained their objections honestly, I think they would fess up to their uncertainty about whether voting to close Guantánamo will have political consequences for them in the next election. In other words, they’re afraid of us, the American people. We all have to take responsibility for closing Guantánamo. We shouldn’t be able to sleep at night knowing that Mohamedou is still there and that there’s no satisfactory explanation and no plan to release him. Let’s insist that there be individual accountability and due process for everyone. We have to send that message to our elected leaders.

BPR: Do you hold out hope of one day meeting Mohamedou?

LS: Yes. This book demonstrates a tremendous faith in the power of the truth. Mohamedou believes that by telling his story as accurately and vividly and empathetically as he can, we’ll read and respond to it. I share that belief. As a writer and a human rights activist, this is what I’ve done for years. I’ve believed in the power of the word.