Two years ago, the United States and the European Union made headlines by announcing new projects to advance the field of neuroscience and offer a comprehensive understanding of the human brain. Like previous government-funded science megaprojects — projects that led to major breakthroughs such as atomic bombs, space travel and a map of the human genome — these projects are ambitious and have huge budgets. They are also the source of one of the most dramatic conflicts in science today — reminding us that such large-scale projects are often uniquely undertaken at the request of well-endowed government — but can also become political fodder.

In the United States, the BRAIN initiative (Brain Research through Advancing Innovative Neurotechnologies) was inaugurated by President Obama and given an initial budget of $100 million annually, which the White House hopes will be a boon to the national economy. The BRAIN initiative’s goal is to further research new technologies that will help scientists understand the brain at the level of neural circuitry. In Europe, the Human Brain Project was launched around the same time. This project, similar in scope and aim to its sister project in the United States, has been promised funding of $130 million per year by the European Union for the next 10 years, bringing the project’s total budget to $1.3 billion. The goal of the Human Brain Project is to create a computer model of the human brain that can then be researched.

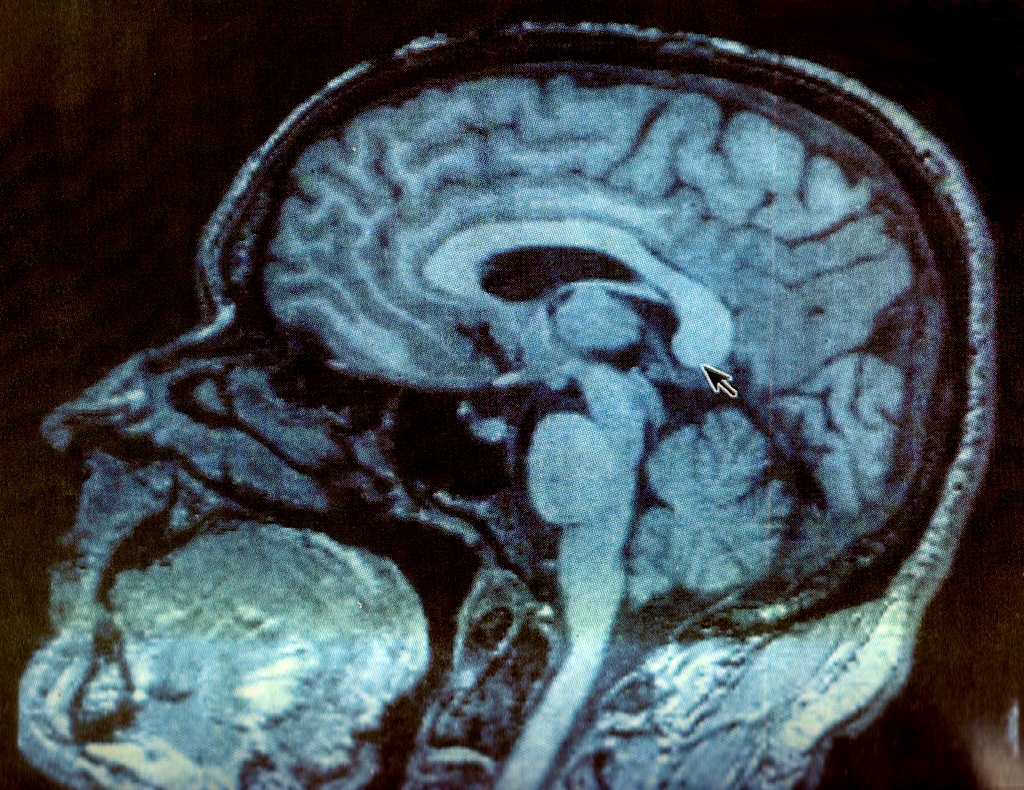

These particular projects seek to fill in a number of gaps in current neuroscience research and may also serve the government through such advances as enhanced interrogation technology, as some commentators have claimed. The first gap these projects seek to fill is the gap between the small and large-scale methods used in brain science. Currently, most neuroscience research takes place on the level of a single neuron or at the level of hundreds of thousands of neurons with very little space in between. Intracellular recording and patch-clamp techniques, which monitor the electrical activity in single neurons, allow researches to study the dynamics of individual cells and how neurons act and behave. Because these techniques require access to an exposed brain, they are, of course, only used in animals and very occasionally in human volunteers undergoing brain surgery for other reasons.

Most human neuroscience uses very different techniques. The ethical limitations of using standard research methods in animal research — which require cutting through the skull, implanting electrodes into the brain, or purposely harming certain parts of the brain — force most human neuroscience to use less precise and less invasive techniques, such as fMRI, EEG, TMS and neuropsychology. Such methods allow researchers to interact with and study the brain without cutting through the skull. Both of these sets of techniques say much about the brain on the smallest and largest of levels of analysis and have done much to inform research in neurobiology and cognitive neuroscience, but they miss a crucial component: the way that groups of neurons connect to each other and influence each other’s behavior.

The brain is estimated to have about 86 billion neurons in total, all of which are in communication with each other through connections called synapses, of which there are estimated to be over 100 trillion in the human brain. Single neurons don’t encode any information on their own; it is the activity of many neurons and the interaction between them where information is stored. And that very realm of neural circuits is one of the least well-understood topics in the brain sciences, the realm that both the Human Brain Project in Europe and the BRAIN Initiative in the United States are trying to investigate. The US project will focus on developing biological techniques to aid in mapping the brain’s circuitry, and the European project will attempt to model that circuitry on a computer.

These projects are all attempts to bridge another gap: the gap between psychology and neurobiology. While this gap has been significantly bridged with existing technologies, much remains to be learned about how the brain gives rise to the mind. In an interview with Time Magazine, John Donoghue, a professor of neuroscience at Brown University and the director of the Brown Institute for Brain Science, who is part of the advisory committee for the BRAIN Initiative, explained that knowledge of circuitry would help us to understand the missing “middle level of analysis. How does the brain transform, ‘I want my coffee cup,’ into reaching out with my hand, grabbing the cup, bringing it to my mouth and taking a sip, effortlessly, naturally, fluidly.”

Projects like the Human Brain Project and the BRAIN initiative have become an integral part of the way that science interacts with politics and with culture. Governments have developed a tendency to fund large-scale projects that unite various members of the scientific community to solve some of the most intractable scientific questions and create novel technologies and sets of data. This model of government-funded projects is different from the way that science is often practiced in academia, with individual researchers and their labs focusing on very specific questions, often in dialogue with one another but without the formal organization of a large-scale project. Oftentimes, these projects have rationales that extend beyond the advancement of science into economic realms. For example, the human genome project, a largely successful project that sequenced the human genome, was founded by the US government in the hopes that it would become a major return on investment, which it was in the end. Moreover, military goals and even national pride often come into play as motivators of scientific megaprojects, as demonstrated by the space race during the Cold War and the potential military uses of new brain technologies alluded to above.

When governments engage in large-scale projects like this, it often leads to a “race.” In the twentieth century we witnessed the “space race” and an “arms race.” Perhaps unsurprisingly, there is now a “brain race,” according to Henry Markram, the controversial leader of the Human Brain Project. China, Japan and Australia have also begun to enter the quest to understand the brain alongside Europe and the United States. Despite Markram’s acknowledgement of a race currently underway, many scientists hope that the project will lead to global collaboration and sharing of knowledge across borders. This does, in fact, seem to be the trend. More recent, post-Cold War megaprojects have begun to involve international collaboration on an unprecedented scale. The International Space Station and the Human Genome Project are prime examples of efforts that combined the expertise of scientists from many countries. As a case in point, the Human Brain Project includes research institutions in the United States, Canada, Turkey, Japan, Israel and China. The quest to understand the brain, and more generally the quest for scientific knowledge and understanding, is poised to be a unifying force for the community of nations.

These large-scale projects capture the nation’s imagination and can be a source of pride, but sometimes the imagination of a nation can lead to problematic action. The Human Brain Project raised the question of whether governments should be optimistic and fund projects with lofty goals, or be more cautious. It remains to be seen whether or not the Human Brain Project will be successful, and with revised and more focused goals it might well be. With the stakes as high as $3.2 billion, however, it seems that the best plan of action would be to set high goals, yes, but ones that are more obtainable. The Human Brain Project seems to be moving in that direction, but its story is a lesson for governments everywhere.

At the same time, the various initiatives in neuroscience across the world underscore the strides made since the era of the space race in terms of international collaboration. Despite the self-interested reasons many countries have for supporting these projects, the projects are also an arena of international collaboration that can’t be discounted. The global community, working together to solve problems fundamental to our existence, has a wealth of positive potential.