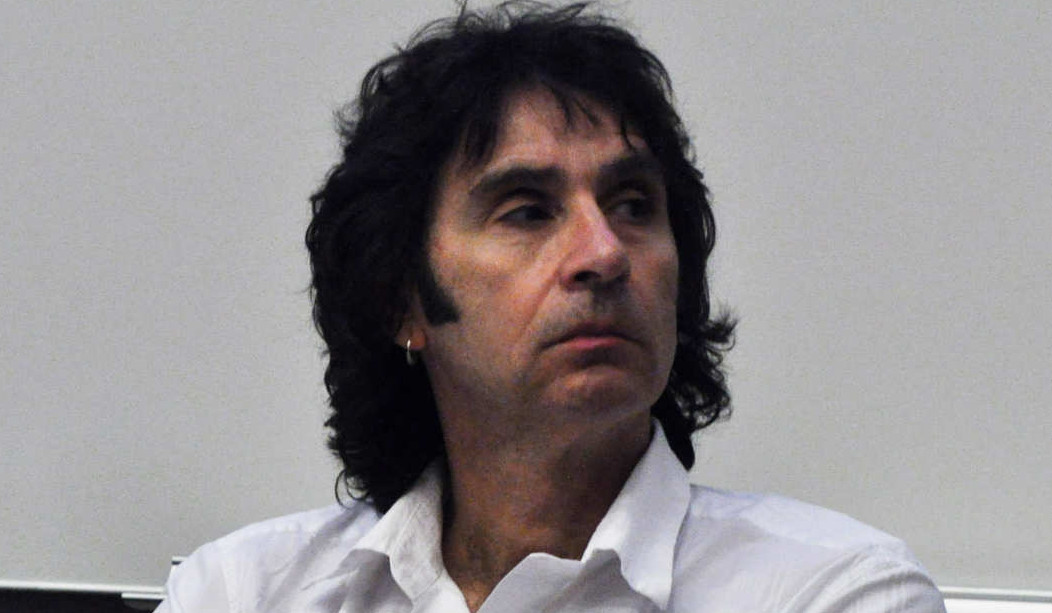

Andrew Ross is a professor of social and cultural analysis at New York University and the author or editor of more than 20 books, including: “Creditocracy: And the Case for Debt Refusal,” “Bird On Fire: Lessons from the World’s Least Sustainable City” and “Nice Work If You Can Get It: Life and Labor in Precarious Times.”

Brown Political Review: What do you think drew NYU to build a campus in the United Arab Emirates?

Andrew Ross: Only money and the ambitions of NYU’s president. If you asked faculty whether or not they thought it would be a good idea to set up a university in Abu Dhabi, none of them would have said yes. The UAE is very wealthy – I think it’s the third biggest sovereign wealth fund in the world – and it has embarked on a nation-building crusade. It is acquiring high-profile cultural assets through brand names like NYU, the Guggenheim and the Louvre. NYU wasn’t the only university the UAE approached, but our president was the one that took the bait.

BPR: What obligations do liberal social institutions have to their workers?

AR: The institution has a very high level of responsibility, especially when it is operating in a society where human rights and labor abuses are rife, as they are in the UAE. In countries and municipalities where employees are organized and have unions, then protection is usually there. A group of faculty and students formed the Coalition for Fair Labor at NYU and pushed the administration very hard to adopt values and fair labor standards. They did eventually do that in 2010, and they were pretty good values. Still, who monitors whether or not these values are being enforced? We have very good labor laws in this country, but they’re not enforced because there aren’t enough inspectors. And in authoritarian societies, there’s no political will to enforce standards. The labor monitor that NYU commissioned to do the oversight fell through on the job.

BPR: Do you see any connections between physical and intellectual freedom?

AR: Yes. The AAUP [American Association of University Professors] exists to define and defend academic freedom. We drafted a policy recommendation several years ago about precisely this kind of situation, where universities go offshore and where there is a very urgent need to protect the rights of instructional employees like faculty and the rights of noninstructional staff, which includes construction and maintenance personnel. It was the first time we’d linked these two in any policy statement.

BPR: What is your critique of the so-called “Gulf paymasters,” who control the wages and working conditions of employees in manual labor positions?

AR: It’s pretty clear to everybody that the reason why our supposedly liberal institutions are going offshore, especially to the Gulf States and China, is because these countries are footing the bill; everything in Abu Dhabi is paid for by the UAE government. Does that mean that the NYU administration has no voice? Does it mean that it cannot protect its own as it is obliged to do?…The NYU case illustrates the larger point about who calls the shots when it comes to the conduct of educational institutions. Increasingly, we have boards of trustees across the country that are composed almost entirely of very rich people drawn from the world of business, and there are very few faculty representatives. What that means is that the shared governance system, which is supposed to be the operating culture within the academy, falls apart and is really only there for show. Under those circumstances, the influence of the trustees, who represent immense amounts of wealth, becomes all-pervasive.

BPR: What are your views on transparency and democracy within universities, both in the United States and abroad?

AR: In private universities, there is very little transparency to begin with. There’s no fiscal transparency and, increasingly, there’s less transparency in decision-making, which is almost unilaterally done by administrations now. Our faculty had no say in the setting-up of branches overseas in Abu Dhabi and Shanghai, for example. So the issue of transparency is key — absolutely key — when it comes to shaping academic affairs and decisions about finances and resources. That’s one of the reasons why we have the soaring student debt problem in this country. And then, if you operate in a culture like the UAE, in which there’s very little transparency whatsoever, then the problem gets magnified and compounded because no one knows what’s going on.

BPR: How might democracy be best cultivated in the university setting?

AR: We have a large faculty group at NYU called Faculty Democracy whose goal is to promote democracy and transparency in decision-making at the university. We advocate for full fiscal transparency and for much fuller representation and consultation with faculty and students, as well as with the communities that host universities, because they’re very much impacted by university policymaking.

BPR: Should American universities abroad expect exemption from a country’s political landscape so that they can be freethinking spaces?

AR: They can’t operate there otherwise. There are no free speech provisions in the UAE. No one else in the UAE enjoys free speech protections. So to operate there, you have to negotiate some kind of agreement regarding academic freedom protections. You couldn’t operate a college without that. That said, there are other colleges in the UAE that predate the introduction of Western colleges into the country, that existed before NYU’s presence there, and they’ve certainly had their fair share of problems in this area, so it’s naive to believe that you wouldn’t run into problems like that.

BPR: What is the intended outcome of your research and writing on workers’ rights in Abu Dhabi?

AR: I would describe my work as advocacy research. Scholars often choose to think and write about communities that don’t necessarily have a voice of their own. To some degree, the research becomes a form of advocacy for the workers in this case, or in general for the communities in question. I’m in a lot of company with any number of NGOs and scholars who are working on this issue. You obviously need research to back up the advocacy, and you need to be able to access the research sites. And the authorities don’t want us to do that, which is why they bar us entry or deport us.