Three weeks after the King College Prep band members performed at President Obama’s second inauguration, they were mourning the loss of a friend: 15-year-old Hadiya Pendleton had been gunned down in a Chicago park. Speaking at the funeral, First Lady Michelle Obama offered words of encouragement to the students who had just said goodbye to their classmate for the final time: “I know you all can live your life with the same determination and joy that Hadiya lived her life. I know you all can dig deep and keep on fighting to fulfill your own dreams.” However, digging deep isn’t always enough for a generation of poor children of color who are almost 10 times more likely to drop out of high school than to graduate from college. Fortunately, there is a strategy with the potential to help millions of at-risk teens overcome the psychological impacts of their surroundings: cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT).

While the physical effects of poverty are easily discernable, its psychological ramifications loom just out of sight. The mental impact of living in areas with high rates of crime — particularly violent crime — has far-reaching and tangible consequences, largely due to stressful life events. A Washington University study found that the developmental effects of high stress levels in childhood may be responsible for the 20 percent achievement gap between poor and wealthy students. Other studies from the National Institutes of Health show that more frequent exposure to high-stress situations causes a disproportionate number of low-income, black youths to suffer from Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD). Even more troubling is the fact that minority groups have less access to PTSD treatment than white Americans do, in large part because of the expense of such treatment, time constraints, and lack of access to transportation. Forgoing treatment is especially harmful for the most at-risk teens, as the psychological damage of poverty can compound the effects of violence. CBT provides a new way to address the mental health problems affecting these communities, improving quality of life and decreasing the threat of gun violence for the most vulnerable students.

CBT is an evidence-based method of psychotherapy used to treat depression and other mental illnesses. The method is grounded in concrete situations, focusing specifically on shaping perceptions and behavioral responses to different stimuli. In this way, it differs from more traditional forms of therapy in that it focuses more on behavior and mindset than on affecting a deeply rooted cognitive identity. In short, CBT seeks to teach individuals how to control their emotions and actions rather than how to control the mechanisms that form emotions in the first place. For example, when using CBT, a therapist could ask a patient to list the problems they encountered during a given time period. The therapist and patient would then discuss what emotions or behaviors might have prevented the patient from solving these problems and come up with a plan for addressing similar incidents in the future. In an interview with Brown Political Review, Ian Levy, a doctoral student at Columbia University and a therapist working with at-risk youth in New York City schools, explains that CBT “provides tangible mechanisms for young people. It’s more focused on ‘what can you do right now?’ — what kind of skills can you work on developing that are going to help you feel better about things you’re facing?”

This “in-the-now” approach to psychology has major implications for people in poor communities — especially those plagued by high rates of violent crime. A Louisiana State University Medical Center study found that people exposed to high-pressure and violent situations at home were prone to the “development of aggressive behaviors and negative emotions.” These sentiments often manifest themselves in a fight-or-flight response, where children struggle to identify and react appropriately to antagonistic situations. University of Pennsylvania criminologist Dr. Sarah Heller explains that street life often conditions poor teens to “develop an automatic response that’s a little bit more aggressive, more assuming that other people are hostile, trying to avoid conflict until it comes and then really strongly standing up for [themselves].” These developmental differences mean that young people who have grown up in poor and violent communities are more likely to respond to tense situations in ways that tend to escalate conflict or inflict self-harm. “I don’t care how much of a hardcore gang member they are or how much they’ve abused substances,” explains Dr. Jaleel Abdul-Adil, co-director of the Urban Youth Trauma Center in Chicago. “Often [those things are] a reflection of a disruption in a developmental process.”

The violence associated with these disruptions in psychological development is a major stumbling block for poor, minority children in their academic careers. The principal school districts in the largest 50 metropolitan areas in the United States have dropout rates almost 20 percentage points higher than the national average. Black students in these areas are disproportionately affected by gang violence and are twice as likely to drop out as their white counterparts. Gang intimidation has historically contributed to high dropout rates in urban areas and continues to pose a significant disturbance for public school districts all around the country. In addition, gun violence presents a critical and ongoing danger to children and young adults in the United States. Nearly 10,000 children are injured or killed by guns every year, and the Center for American Progress anticipates that firearms will become the leading cause of death for people ages 19 to 24 at some point this year, ahead of car accidents.

On July 4, 17-year-old Vonzell Banks was shot dead while playing basketball in a public park named after Hadiya Pendleton, the girl whose death Michelle Obama had honored just two years prior. The violence that afflicts inner-city teens is cyclical and ceaseless, yet despite its enormous harm, poor teens of color have precious few resources to help address the ensuing mental health concerns. Levy, the Columbia doctoral student and New York City school counselor, states that, “Generally, within schools, there’s a lack of focus on mental health services and on really creating spaces to give students opportunities to be self-reflective, to digest difficult emotional experiences.” The Washington Post reports that almost 90 million Americans live in “mental health professional shortage areas,” with 45 percent of those who forgo mental health care treatment citing cost as a major barrier. “Obviously, there’s a lot of violence and drug use within these areas as well that would subject young people to emotional struggles, but more importantly, when they face those struggles, there’s a lack of outlets for them to digest them,” Levy explains. “I think the onus is actually on the people in positions of power to create spaces for those young people, to create these outlets for them.”

Yet instead of expanding much-needed mental health services to urban teens, city lawmakers have often squandered money on more traditional violence prevention programs that lack clear impact. In 2009, Chicago Public Schools (CPS) began funding an anti-gun violence initiative, known as Youth Advocate Programs (YAP), which was meant to protect its low-income, minority students. According to “Freakonomics” co-author and University of Chicago economist Dr. Steven Levitt, YAP was “one of these urban programs where they had mentors and they came in and they tried to coach the kids and teach them to do the right thing. That sort of stuff.” In a city rife with gun violence, this sort of effort is an understandable policy response. But Levitt’s lack of enthusiasm for the program is justified — its results were disappointing. In the 2011-2012 school year, 319 CPS students were shot. While this accounts for less than one-tenth of a percent of the total enrollment of around 400,000 students, a study published in the American Economic Review revealed that the most at-risk teens in CPS had only a 2 percent chance of being shot — for the CPS students who participated in YAP, this was a staggering 6 percent. While some of the disparity may reflect the selection bias inherent in a program designed for at-risk students, the numbers still indicate that YAP did not do enough to protect its participants.

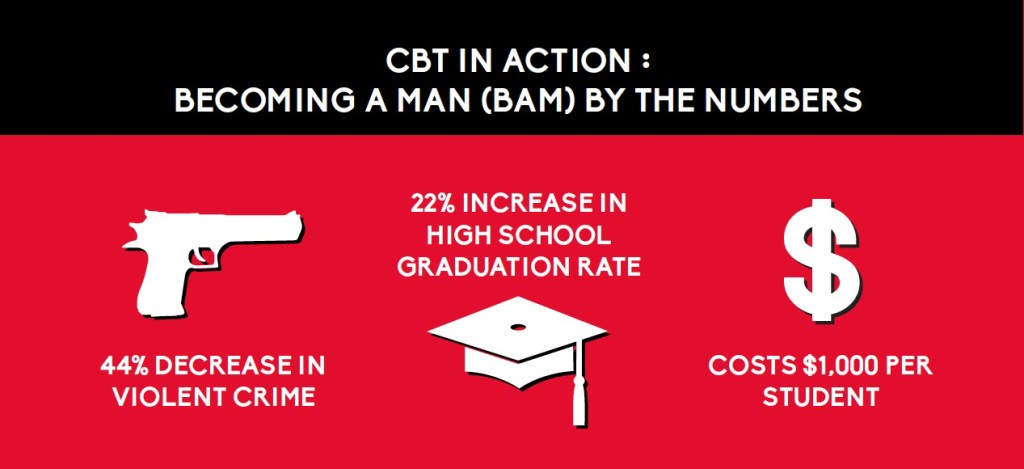

CBT appears to be a superior alternative to programs like YAP. In 2010, the University of Chicago’s Crime Lab found that just one year of CBT training through the Chicago-based CBT program Becoming a Man (BAM) decreased the violent crime rate of participants by 44 percent. A 2012 study published in the journal Science found that One Summer Chicago Plus, a program focused on offering CBT and summer jobs to low-income youth, provided a similar 43 percent decrease in violent crime. This is a monumental improvement. CBT program participants also enjoyed positive effects outside of the realm of violent crime. A review from the National Bureau of Economic Research found that BAM students were also more engaged in school and had higher attendance rates, which it suggested will lead to an increase of as much as 22 percent in the high school graduation rates of participants.

To understand why CBT is so effective, just take BAM, which uses CBT as a technique to engage at-risk teens in ways that relate to them. Tony DiVittorio, the creator of BAM, explains that the program focuses on the theory of “the normalization of anger,” which “opens up that student and frees him to talk about [anger]” in order to find a healthy way to channel these emotions. The program has focused predominantly on black males due to their disproportionate likelihood to be victims of gun violence. DiVittorio explains that these programs have a unique appeal: “When they come out of class for this week, they’re not coming to therapy, they’re not coming to a program where they have to start talking about their feelings, they’re coming to a program that is a hook.” Student engagement is critical to CBT programs’ ability to get results; in their first few sessions, time spent at BAM is often focused on games, sports, and role-playing. The latter is one of the most important tools in CBT.

Role-playing activities can be incredibly productive for participants in CBT programs, as they allow participants to practice more effective responses to troublesome situations. Columbia University economist Chris Blattman describes a normal activity for a CBT session as involving two participants role-playing in front of the group, where one participant is instructed to insult another. “It’s not a real situation of anger, but the guy who’s insulted now has to come up with something he has to say or explain what he’s going to do and role-play how he’s not going to react.” Because CBT exposes participants to charged situations in a safe environment, these teens can develop strategies for handling their emotions. “You’ve got to start recognizing that the kids are not just bad and they’re not just mad,” says Dr. Abdul-Adil. With the core support of a group of peers and a close relationship with their CBT therapist, these teens can find new, positive ways to handle negative emotions and charged situations.

CBT is also an effective tool because of its applicability in different cultural contexts. California State University, Fullerton psychologist Dr. Gerald Corey explains, “Cognitive behavior therapy tends to be culturally sensitive because it uses the individual’s belief system or worldview as part of the method of self-exploration.” Unlike more traditional therapy, CBT encourages individuals to explore their emotions from the perspective of their own background and their own social environment. As such, CBT participants learn that frequently hostile environments do not preclude them from responding nonviolently to provocation. Levy explains that this is especially important because “there’s definitely this focus that young people have on maintaining masculinity. If you’re perceived as weak within a lot of these communities, it can be detrimental to your ability to be successful.” By teaching its participants how to manage their emotions within the structures that define their identity, CBT makes violence prevention far more accessible.

Vincent Rosaro, a graduate of the BAM program, describes himself as having been “kind of a lost cause,” because he “grew up in an environment of drugs and alcohol and abuse and gangs.” Millions of students in the United States grow up just like Rosaro but do not receive the support they need to succeed. Without that help, what lies beyond for many of them is a world of crime, violence, and incarceration. “One of the things I tried to help [Rosaro] to see was that even though he was justified for feeling the way he was in class, the way he was expressing himself was not getting [him] what he wanted,” says DiVittorio. CBT programs allow teens to channel their emotions in new ways that can help them succeed in the classroom, thrive socially, and, perhaps most importantly, avoid the threats of violence that plague a generation of disadvantaged youths. “I love this guy,” Rosaro says of DiVittorio, “because he understands what it takes to fight through those emotions.”

CBT’s effectiveness as a program doesn’t necessarily guarantee its viability as a policy initiative. US public school districts aren’t exactly swimming in cash, and many have been forced to make major cuts in recent years. Districts that are laying off teachers by the hundreds can hardly afford expensive violence prevention programs. The good news is that CBT is significantly more cost-effective than other violence prevention methods for poor teens in urban areas. For example, YAP, BAM’s underwhelming predecessor, cost $20,000 per student; BAM, on the other hand, costs only $1,000 per student. Further, CBT-based violence prevention programs come with an array of economic benefits that go far beyond the simple expenditure of the school district. Violent and nonviolent crimes, as well as high dropout rates among high school students, have huge economic ramifications. Effective CBT has been shown to reduce all of these costs — and then some. The University of Chicago estimates that a version of BAM created economic benefits anywhere from 3 to 31 times larger than the cost of the program.

Despite its benefits for participants and society at large, CBT is not without its critics. The primary problem with CBT stems from its design. Because it is such a present-centered form of therapy, its effects tend to dwindle significantly with time. While violent crime rates decrease by about 44 percent the first year after CBT for participants, the effects during the second year are statistically insignificant. But Dr. Heller argues, “violence is incredibly socially costly, so if there’s a way to reduce violent crime, even for just a year at a pretty low cost, we should do it.” Furthermore, CBT decreases rates of violent crime during a critical time period, since crime rates for individuals are highest in their late teens. If CBT significantly reduces violent crime during these key years, both the participants and society at large will enjoy tremendous benefits.

CBT-based violence prevention programs have yet to be created around the country, and the burden of implementation is largely on local lawmakers, primarily at the district level. Providence, RI, for instance, could benefit greatly from a CBT program for at-risk students. Gang violence permeates the city, with powerful gangs such as “Pine Street” and “C-Block” influencing large parts of its southern and eastern neighborhoods. Gang members frequently commit violent crimes that destabilize communities and threaten youths. Between 2008 and 2012, 22 teens in Rhode Island died due to gun-related incidents, and 65 were hospitalized. As this issue disproportionately affects poor adolescents of color, the city’s NAACP branch has publicly urged the government to allocate substantial funds for the prevention of violence among at-risk youth. For the Providence School Department — which spent $544,000 on dropout prevention, guidance, and social services in the 2013-2014 school year alone — a $1,000 per-student CBT program for the district’s most at-risk teens seems a small price to pay to keep students from slipping through the cracks.

On a broader scale, offering CBT to at-risk students will decrease basic inequality in the US educational system. Public schools do not give minority students a fair deal. The 2013 National Assessment of Educational Progress found that only 7 percent of black 12th grade students were proficient in math, while 33 percent of their white counterparts achieved mathematical proficiency. Funding contributes greatly to this problem, as most public school districts receive funding proportional to the property taxes of the surrounding neighborhood, leaving schools in poor areas out to dry.

Nonetheless, at the heart of the problem lie the structural conditions that cause many low-income, minority children to develop coping mechanisms that lead to violent behavior. Within the bounds of a justice system that disproportionately penalizes minorities, such behavior has lasting effects for both the individuals involved and their communities. At both the state and federal levels, the government can begin to address these enormous disparities by funding CBT programming for poor, urban schools. Chicago’s programs have shown that these methods can work in some of the toughest neighborhoods. Extending CBT-based violence prevention initiatives to the nation’s most destitute and gang-afflicted schools would allow for positive changes inside and outside the classroom. More importantly, it would help give a fair chance to a class of students for whom the American dream remains virtually unattainable.

The deaths of Hadiya Pendleton and Vonzell Banks — both shot in cold blood in public parks — are tragically important for a country in which many children fear for their lives on a daily basis. Now more than ever, the United States needs cost-effective measures to help protect at-risk teens from the perils of gang and gun violence. Innovative approaches, like access to CBT, are strategic necessities in combating this devastating problem. If American lawmakers push to implement CBT in cities across the country, perhaps our nation’s policies will enable Hadiya’s classmates to live free from the violence that took their friend.

Layout by Jackson Dobronyi