In 2014, the events leading up to and following the referendum on Scottish independence dominated news coverage around the world. The idea of an independent Scotland was particularly intriguing as many international observers saw the UK as a cohesive unit. A Scottish split would have not only changed the nation’s identity, but also transformed global structures ranging from the United Nations Security Council to the Olympics. Although the Scottish referendum narrowly kept Britain intact, the 2015 General Election saw the Scottish National Party, which led the independence push, dominate Scottish politics. The aftermath of the Scottish referendum clearly indicated that the question of independence is only temporarily settled; it remains both actively and subconsciously present in many of Britain’s leading policy issues today.

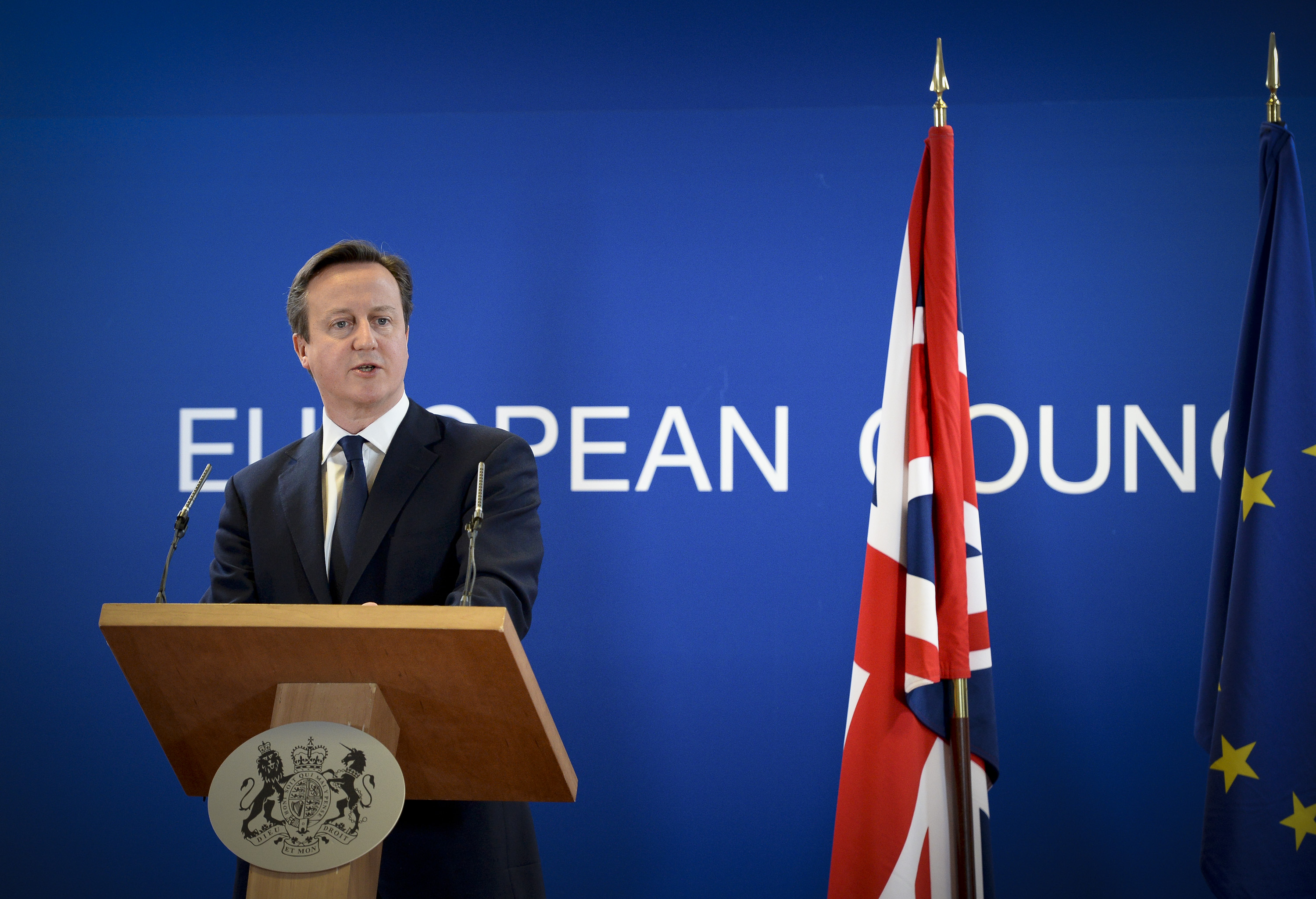

Now, an international spotlight once again shines on the British public’s opinion. As long as the UK has been a part of the European Union, there has been a debate over whether this membership is beneficial or detrimental to the national interest. From its geographic isolation to abstaining from the adoption of the Euro, Britain has never been wholly invested in the EU, and now Brits are wondering if the benefits of membership are truly worth it. In response to the growth of the anti-EU UK Independence Party and anti-EU forces in his own party, Conservative Prime Minister David Cameron vowed during the 2015 election that he would hold a referendum on the UK’s membership in the EU by 2017. That timetable has since moved forward, with the referendum, nicknamed Brexit, scheduled for June 23. The upcoming EU referendum and the recent Scottish referendum appear to be parallel narratives that have jointly dominated recent British identity politics. While these two votes are, on paper, independent, they are in reality intricately interlaced. This relationship provides insight into the challenge of British unity and the understated importance of Scotland in the upcoming referendum.

David Cameron spent most of last week in Brussels frantically attempting to secure his extensive “wish list” of proposed reforms to the terms of the British EU membership. As of February 19, these efforts appear to have translated into a formal deal between the two parties, and a series of changes, which constitute a significant portion of Cameron’s wish list, have been confirmed. The deal contains major reforms on immigration policy, economic policy, and the structure the EU and UK’s political relationship. For example, Britain now has the right to exclude non-EU nationals who have married EU citizens from freely entering the country as well as bar parties suspected of being security risks regardless of whether they have been convicted of a prior crime. Fiscally, Cameron has long pushed for protection of British economic interests in the EU and has sought rules to ensure that banks and investment firms in London will not be burdened by the use of an alternative currency — a reality for only 9 of the 28 EU member states. These policies, as well as a specific effort to avoid the “political integration” of the UK into the EU, reflect the overarching sentiment of the Conservatives, who are eager to prevent future infringement upon national sovereignty.

Unsurprisingly, Cameron’s demands have been met with significant push back from within the Union. The EU has voiced a legitimate concern that granting Cameron his desired reforms would prompt future efforts by other countries to produce their own list of demands. “Eastern European nations, from which huge numbers of workers in Britain have come, are wary of welfare restrictions, fearing the new rules could give their citizens second-class status. France is worried that the proposals related to the financial industry might give British companies an unfair economic advantage. And Belgium is unhappy about a British effort to pull back from an ‘ever closer union,’ fearing it may weaken the bloc’s ambitions,” according to Stephen Castle. In fact, Belgium and France have been at the forefront of the opposition to Cameron’s adamant efforts, voicing a “Brexit warning” that any decision made by the referendum will be binding and irrevocable in the final rounds of negotiations.

However, the fundamental problem with Cameron’s wish list, no matter the international pushback or outcome, is that it has solidified the domestic divide among the British people and brought one of the nation’s most polarizing policies to the forefront of debate. In last May’s elections, the Scottish National Party won 56 of 59 Scottish seats in the House of Commons, with the Conservatives, Liberal Democrats and Labour winning one each. This means that although the Conservatives have a majority in the House of Commons, they lack a mandate in Scotland. And while Prime Minister David Cameron has campaigned on a platform of moderate reform, many of his more conservative counterparts have been driving the Brexit campaign with their full political might. The mayor of London, Boris Johnson, who is expected to make a bid to replace Cameron, framed the Brexit campaign as an unfortunate, but necessary step to maintain British sovereignty, rejecting the “supranational element” at the core of the Union. While the majority of the country does not match his level of conviction, the Brexit campaign still poses a risk to British unity for the simple reason that the Scottish population neither supports the Conservatives nor shares their opinions on EU membership. As a result, there is a very real possibility that Brexit may lead to “Scexit.”

Speculation of this causal relationship — formerly more of a behind the scenes discussion with relatively little political or public focus — has recently escalated. Nicola Sturgeon, First Minister of Scotland and head of the Scottish National Party, announced that if Britain left the EU, Scotland would “almost certainly” call for a second vote of its own. The relationship between Brexit and the Scottish referendum is far from clear-cut, but the intersection of the two will assuredly alter Britain’s identity internally and externally. And yet, despite clear concerns in Scotland with the prospect of Brexit, Cameron repeatedly stated that he “will be battling for Britain,” and that “with goodwill, with hard work, we can get a better deal for Britain.” Now, a deal has been confirmed and a date for the referendum is set. But these assurances — and perhaps the success in following through on many of them — convey the problem with the EU reform and referendum efforts in the first place. The Britain that Cameron claims to represent drastically differs from the Britain that Scotland sees and envisions for the future. Whether voiced through the 2015 general election that placed the Scottish National Party in nearly every Scottish seat, or current polls that reveal resounding Scottish pro-EU sentiment, Scottish and British identity appear for the first time to be truly separate entities. There could not be a more fitting analogy for the current dynamics between the UK and Scotland than the UK-EU relationship itself. According to the Conservatives, the UK has always been treated as an outsider in the EU; membership has sometimes benefitted Britain and has sometimes had minimal to no impact, but overall, it has not led to mutual exchange and benefit. For many Scots, namely the National Party, these sentiments also narrate the relationship between Scotland and the UK. While one cannot deny many of the economic and political advantages of Britain, it seems like major political decisions divide the two parties far more often than they unite them.

However, despite the plethora of important political conflicts between the current government and the Scottish people, the most dangerous aspect of the EU referendum may actually be the ambiguous and ambivalent attitudes that many have toward the vote. Even without the Scottish implications, the ramifications of the referendum are understood to be widespread; the vote will no doubt have remarkable political, economic, and cultural consequences for the nation. Yet, much of the public appears to be undecided or expressive of “soft euroscepticism,” a broad hesitancy to establish closer ties with the EU. In other words, the strength of people’s convictions does not reflect the strength of the implications. Amid this general lack of conviction, the opinions of the Scottish population appear further isolated. Brexit is a Conservative creation and Scotland is decidedly not. Brexit could become a reality, despite the united front Scotland presents, if the Conservatives succeed in convincing the relatively unenthusiastic population — primarily the English portion that they represent — that it is in their interest to leave the Union. Thus, the UK could depart from the EU predominantly on the will of the English, leaving Scotland out to dry. In the end, the mildly interested majority, in its attempt to secure what it considers best for Britain, may inadvertently lead to its failure.