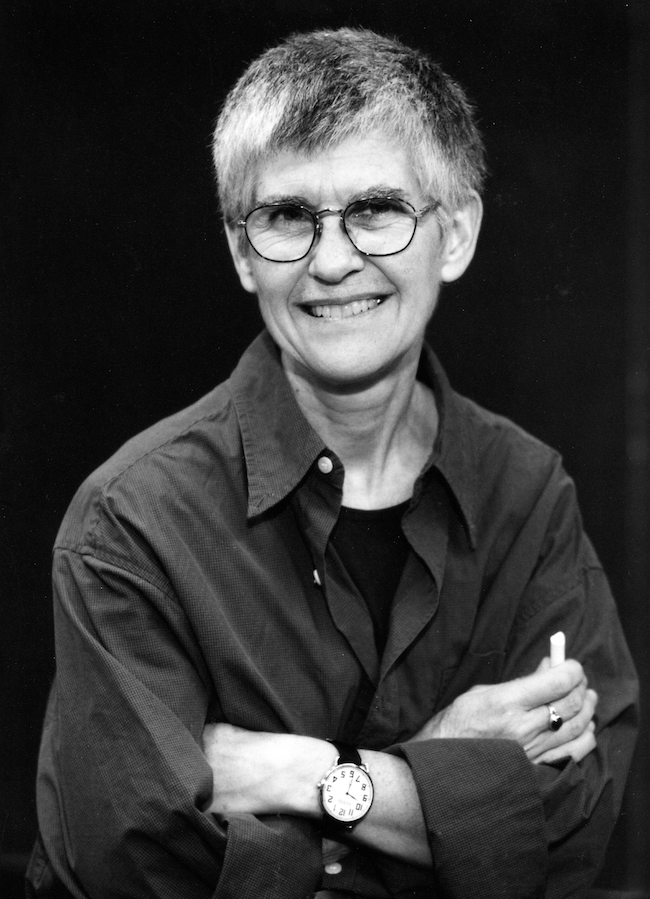

Cynthia Enloe is a feminist international relations scholar in the Department of International Development, Community, and Environment at Clark University. She has written fourteen books, including Seriously! Investigating Crashes and Crises As If Women Mattered and serves on the editorial board of several academic journals, including The International Feminist Journal of Politics.

What was your personal trajectory in cultivating your feminist identity?

I didn’t ask feminist questions about politics until after my PhD [nor] even after I’d published six books. I also wasn’t asking feminist questions in the first courses I was teaching. It took friends to push me towards feminist questions and to make me more engaged with feminist activism; this was in the mid-1970s. I began to realize that my personal life was affected by gender stereotypes, sexist attitudes, and sexist politics. I started asking, “If I’m becoming aware of it in my own life, in my academic and employment life, then, shouldn’t I be asking feminist questions of the things I study and teach?” That began to fully evolve in 1975 and 1976. I was pushed by students at Clark University who wanted to know why I didn’t talk more about women in militaries when I was doing a lot of work on racism in militaries around the world…At the same time, British feminist friends who were working on all kinds of issues of sexism in Britain started pushing me to ask the same sorts of questions about the textile industry, policing, and employment.

Once you start asking questions that you’ve never asked before, you can’t stop asking them. You begin to say to yourself: “Oh my gosh, I can’t understand policing, I can’t understand the garment industry, I can’t understand elections unless I ask feminist questions.” I began to not be able to not ask them. It was so exciting because it really affected my teaching as well.

How do you reconcile your feminist identity with your work as a scholar?

I think it made me a better scholar, a better teacher, and a better writer, because now I was asking much more detailed, realistic questions about the workings of power. Becoming a feminist didn’t mean I always knew the answer; becoming a feminist for me meant that I had very pointed questions to ask that I had spent years not asking. And, when you have better questions to ask, your thinking gets better.

How do your own position, identities, and background affect your work and approach – especially in regard to your approach to globalized issues?

I think that feminists from all over the world…insist that they themselves, as well as any of us, should be reflexive. Reflexivity means that you’re conscious, that you don’t ever slip into the presumption that, because you have a higher education degree, somehow your own personal experience and your own personal attitudes don’t matter. Reflexivity means that when you do research, you always have to think – who am I in this situation?

You understand that the people you’re asking to be so generous as to give you their time think about you. It’s not just you thinking about them. That’s the only way you can overcome the very unequal relationships between the interviewer and the interviewee. In a lot of settings, that power quality really warps the interview. So, to use feminist research methodologies means always to be conscious about the workings of power and dynamics of inequality in a research project. I just came back from Sarajevo, where I was asked to take part in Bosnian feminist conversations. I was very aware that I was the only American in the room. I really had to listen very hard to make sure I didn’t use American examples as if they were normal. You just never can assume that your own experience is the normal experience, while everybody else’s experience is somehow odd and worthy of research.

What is your stance on bringing men into the debate on gender equality, femininity, masculinity, and gender? In your experience, how do men approach these issues?

It is true that a lot more men are asking those questions now. In my classes and in the lectures that I give in various places, there are always young engaged men in my audiences…Nowadays, I have a lot of male colleagues in various countries who realize they can’t make sense of the things they care about, whether it be rising anti-immigrant attitudes, rising violence or rising inequality, if they don’t learn how to ask feminist questions and do feminist investigations. What they realize is that they have to therefore be reflective of their own masculinities.

A lot of men, particularly if they’re in some sort of privileged academic, economic, or political position, are nervous about asking serious, reflexive questions about their own presumptions about manliness. They’re more than willing to ask a couple of superficial questions about other men’s masculinities–such as the masculinities at work amongst people who go to fight with [ISIL]. That’s very different, however, than asking about their own masculinized privileges.

If the study of masculinities is not done with an interest in the workings of sexism, the workings of patriarchy, and the workings of femininities, then what you have in fact is just men’s studies. It’s just a newly fashioned form of what we’ve had in academia forever. So, to do serious work on masculinities, there has to be an explicit feminist curiosity about the lives of women. To claim that making a serious effort to understand the complex workings of women’s and girls’ lives is not political–that’s sexist.