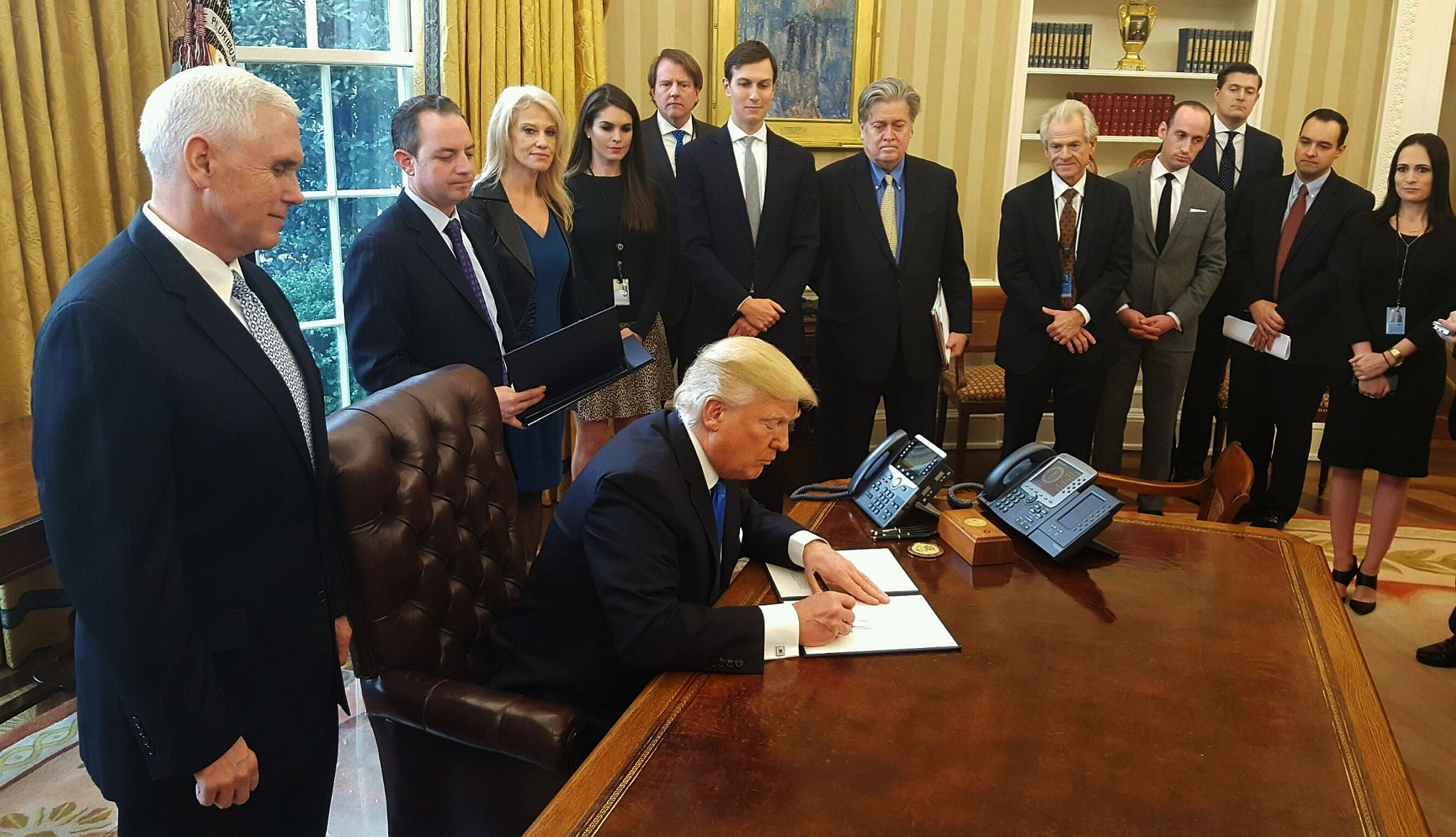

The beginning of Trump’s presidency was marked by a flurry of executive actions. In his first twelve days in office, President Trump issued eighteen executive orders and presidential memos. Although this behavior from the administration is surprising considering Trump’s harsh criticism on the campaign trail of President Obama’s use of executive actions, the use of executive actions at the beginning of a presidency is quite normal; moreover, despite the attention-grabbing content of Trump’s executive actions, his seem to contain more bark than bite. Because of legal challenges and vague language, Trump’s executive actions are more symbolic than substantive.

Although executive actions are never mentioned in the Constitution, they have been used by every administration since George Washington’s. A tool for both liberals and conservatives, executive actions have been used for progressive and oppressive agendas: For instance, both the Emancipation Proclamation and the forced internment of Japanese Americans during World War II were carried out via executive orders. Though a powerful tool, executive actions are limited in their ability to create long-term, substantive change in policy. They can’t be used to appropriate new funding from the Treasury or to change existing law — rather, they are meant to work within the parameters of existing law. This means that executive actions must be very specific about how agencies should direct the resources that have already been allocated to them in order to create substantive results.

According to presidential historians, the volume of Trump’s executive actions is well within the average range for incoming presidents. During the first twelve days of his presidency, President Obama signed nineteen executive actions, constituting a slightly higher rate than that of President Trump. Obama’s early executive decisions mostly focused on increasing transparency in Washington, loosening detention policies, and pushing for more progressive environmental policies.

New presidents have an incentive to sign executive actions early on in the presidency for several reasons. First, executive actions allow the new administration to clearly communicate its policy agenda and to relay to relevant government agencies what issues the new administration will prioritize. Second, executive actions, especially early on in the presidency, give the impression that a president will keep promises made during the election cycle. This was true for the executive actions issued early on in President Obama’s first term, nearly all of which were closely related to his 2008 campaign platform. However, the danger of executive actions is that public opinion tends to favor presidents who act legislatively rather than unilaterally. Thus, while executive orders are a flashy, symbolic way to set the agenda early on in the presidency, most administrations do the bulk of their signature policymaking through Congress.

Indeed, many executive actions signed early on in a presidency have little bite to them. Obama signed his executive order to close Guantanamo Bay in his first week in office and called for the detention facilities to be reviewed and closed “as soon as practicable.” Though the executive action made a significant political statement, it was ultimately unsuccessful in closing the facility. President Trump’s executive orders will likely follow a similar trajectory. For instance, the new president’s very first executive order, signed on his first day in office, ordered government agencies to minimize the economic burden of the Affordable Care Act. Despite the political symbolism of this action, the text of the executive order is too vague to be enforced in a meaningful way and does not direct agencies with a plan of action. Similarly, Trump’s executive order to start building a border wall between the US and Mexico might urge the Department of Homeland Security to start planning the wall, but Congress would have to approve funding for the hiring of thousands of new border control agents and for the construction of the entire 2,000-mile wall. As a result, this executive action — though it makes for good headlines — can easily be ignored by government agencies, and will fail to actually affect change until Congress supports the administration’s agenda with new legislation.

Even Trump’s most controversial executive actions are unlikely to be implemented in the long term. Right from the outset, both the suspension of federal aid for sanctuary cities and the ban on immigration from seven Muslim-majority countries faced well-founded legal challenges. Several mayors from sanctuary cities have vowed to fight the executive order, and the city of San Francisco filed a lawsuit in a northern California District Court against the executive order, claiming that it violates the 10th Amendment, which reserves powers for the states. In an even more dramatic backlash, Trump’s Muslim ban was in effect for less than a week before the Department of Homeland Security was forced to comply with an order from a federal judge to suspend all actions implementing the executive order — a decision later upheld by three judges on a federal appeals court panel.

Some might view Trump’s Muslim ban as a reversal of Obama’s controversial executive order on immigration in June 2012: Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals (DACA). DACA allowed undocumented immigrants who entered the US as minors to apply for a two-year period of deferment from deportation and to receive a work permit. However, the two actions differ in a crucial way; DACA was issued after four years of attempts by the Obama administration to pass immigration reform through Congress. DACA was modeled on the Development, Relief, and Education for Alien Minors Act (DREAM Act), a bill that would provide temporary legal residency for undocumented immigrants who entered the US before their 16th birthday. The DREAM Act passed through the House of Representatives and was supported by a majority of 55 senators, but nevertheless failed to pass in the Senate because of a Republican filibuster. The Obama administration subsequently issued DACA, which enjoyed broad public support. Although there are few studies on the relationship between public opinion and use of executive actions, one 2016 study found that while people tend to disapprove of unilateral action by the president, public support for unilateral action increases by 20 percentage points in the case of Congressional gridlock. Meanwhile, Trump’s Muslim ban was allegedly drafted without consultation with the head of Homeland Security and other top leaders and, according to a CNN/ORC poll, a majority of Americans oppose the travel restrictions put in place by the executive action. This suggests not only a disregard for public opinion, but also an alarming break from the norm of cooperating with Congress to advance major policy goals.

This comparison shows us how unusual Trump’s use of executive action truly is: Where other recent presidents have used executive actions symbolically in the early years of their terms, or (as in the case of DACA) as a last resort for getting things done in the face of Congressional gridlock, administrations tend to rely most heavily on legislative action to advance the policies that they care most about. By rolling out his signature policies through executive actions, Trump is demonstrating that he is either unable or unwilling to work with Congress to create more substantial legislation.

So far, President Trump breaks from other presidents in his reliance on executive actions alone to advance his policy agenda. As the New York Times pointed out, the Trump administration has not yet introduced substantial legislation into Republican-controlled Congress. In contrast, President Obama had introduced a $1 trillion stimulus package to Congress after less than a month into his presidency, and President George W. Bush introduced a 30-page blueprint for his major education reform bill, No Child Left Behind, just three days into his first term. Congress, meanwhile, has spent most of its time struggling to confirm Trump’s cabinet picks, while promised efforts to overturn the Affordable Care Act, overhaul the tax code, and introduce a major infrastructure bill have stagnated. And in a campaign heavy in rhetoric and light on policy discussions, it’s unsurprising that the administration is unprepared to pass the sweeping legislation it promised and is instead relying on executive actions to give the appearance of headway.

Even though the use of executive orders early on in a presidency is not abnormal, Trump’s specific actions suggest an extreme departure from the norm. Despite the unlikelihood that his most controversial executive actions will be implemented, their content is a shocking wake up call for the people who argued that President Trump would refrain from attempting to implement his more dramatic campaign promises. Moreover, his rushed executive order banning immigration from seven Muslim-majority countries, seemingly without consultation with legal or national security experts, shows a disregard for legal limits on his desired policies. Finally, his reliance on executive actions as the main vehicle for advancing his major campaign promises reveals the deep inexperience in his administration. Trump does not have a game plan for introducing detailed, legal policies through Congress, and his reliance on executive actions illustrates that. Nevertheless, the administration seems eager to keep up the impression of getting things done: In his most recent press conference, Trump declared, “there has never been a presidency that has done so much in such a short period of time.” But unless the Trump administration manages to legislate through Congress rather than passing largely symbolic executive actions, this statement will remain as meaningless as his ineffectual executive orders.