John Maynard Keynes needs no introduction as the most important economist of the 20th century. His theories have shaped modern economics like few others. However, his vision for the international trade system, or bancor for short, has been mostly forgotten.

As with anything even remotely Keynesian, the idea of bancor had a mini-resurgence in the wake of the 2009 crisis. George Monbiot wrote an article regarding bancor in the Guardian and the governor of the Bank of China, Zhou Xiaochuan, praised the idea in a speech. But this buzz has since died down.

Bancor is a radical rethinking of international trade. It is a system in which countries would deposit their national currencies in exchange for a set amount of bancor. Bancor isn’t technically a currency, and it can’t be owned by private actors, whether ordinary citizens or large multinational corporations. It is instead a kind of retrospective unit of accounting.

To function, this system would require an international clearing house (a bit like the IMF today).

Trades between nations would be recorded, and every export would be tallied as additional bancor tokens, while every import would be a subtraction of bancors. As with any clearing house, members will net trades out with each other. In this process, there will inevitably be an imbalance of exports and imports, as we see today. However, the focal difference is that the bancor system would try to correct these imbalances automatically.

Small deficits or surpluses are not harmful. However, when they are prolonged or large in magnitude they can cause much trouble.

It is true that according to neoclassical economics, trade deficits will improve in the long run due to the J-curve effect. Since more funds are flowing outward than inward, the deficit country’s currency will depreciate. Then the depreciated currency will make the deficit country’s goods more attractive, which finally improves the trade balance.

This is a powerful mechanism, and it has indeed corrected certain imbalances. But some countries seem to be perpetually uncompetitive in international markets, and a perpetual current account deficit is not doing the deficit country any favors.

In order to finance the current deficit, they would have to fund their capital account, which usually means a sale in assets or the borrowing of foreign money. These would either result in an increase in interest-payments or a fall in productive assets, reducing the welfare of future generations.

If the deficit is a temporary measure to bring in productive assets, then great. But, it seems that some uncompetitive countries are using the deficit to purchase consumption goods.

Essentially, this is the rationale for the existence of bancor: its constitution is fundamentally dedicated to eradicating any large surplus or deficit.

The bancor system would function as follows: When a country has a deficit, surplus countries will be forced to take their surplus reserves and give it out as loans.

To incentivize the importing country to avoid accruing current account deficits, there is interest charged on the loan, once their deficit has exceeded a certain level of GDP.

But there are more interesting aspects: Since this loan is issued automatically, the conditions are the same regardless of the particular situation of the country. No more loans conditional on controlling inflation or on restricting public spending. Hence, the conditions of the loan should be less onerous on the deficit-plagued countries.

The second feature, curiously enough, is a negative real interest rate charged on surplus countries. In other words, surplus countries pay interest on the loans they issue. They have to accept such conditions since the international clearing bank would force them to give out these loans. The reason for this bizarre policy is to incentivize surplus countries to spend their surplus on products from the deficit countries. If this works ideally, a virtuous cycle is triggered: countries start stimulating the aggregate demand of one another. So this system does not merely pay lip-service to fixing trade imbalances, it does so both automatically and forcefully.

In theory, the clearing bank’s balance sheet could expand indefinitely. This might sound dangerous or irresponsible, but it isn’t, especially when you consider that domestically, this is what central banks do.

The US Federal Reserve, for example, more than quadrupled its balance sheet in the wake of the financial crisis. Besides, unlike current central banks, the balance sheet of the International Clearing Union (ICU) will only rise or fall in proportion to deficits and surpluses. If trade balances are near zero, which is the very intention of bancor, the balance sheet of the ICU would be empty.

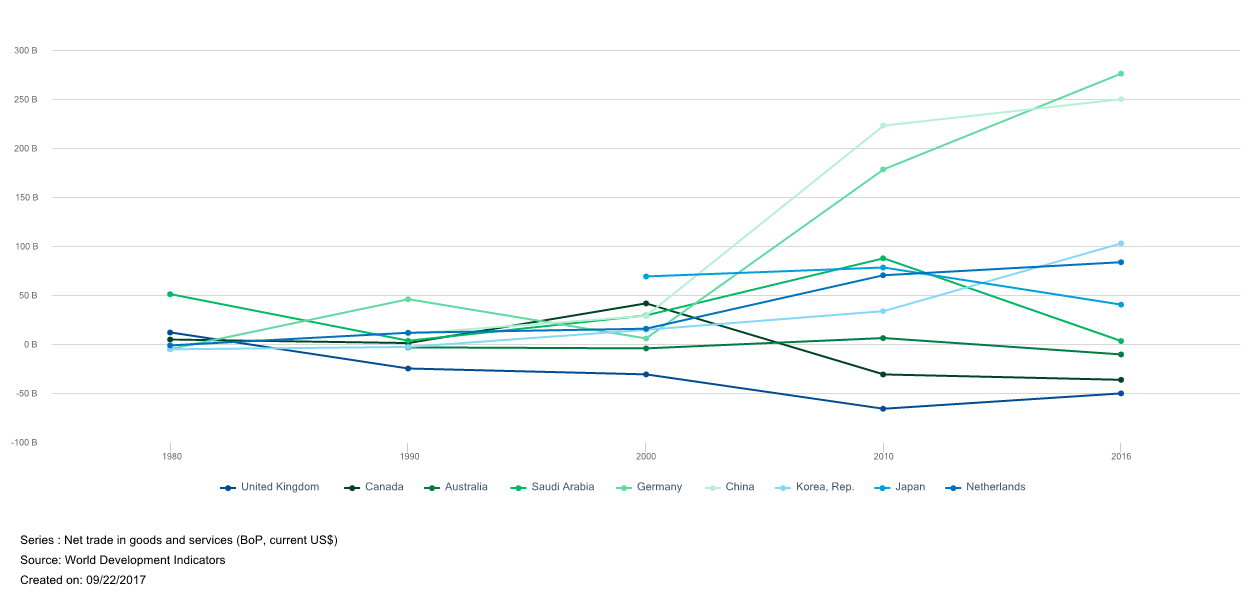

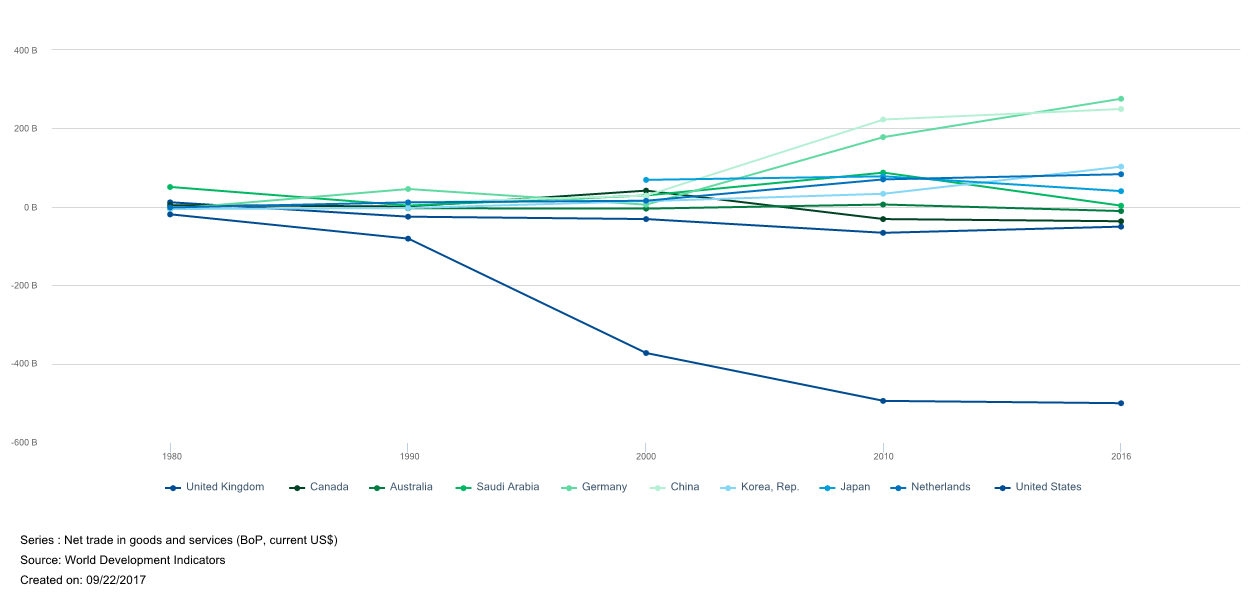

This ability to indefinitely expand the balance sheet bestows the status of international “lender of last resort”, a role that no organization properly fulfills today. The Fed is too focused on its own domestic issues to play the role of international lender, and there is evidence that the IMF’s somewhat harsh approach to lending has been pernicious. These two graphs plot the trade balances of the five top surplus countries and five top deficit countries from 1980 to 2016. The second of the graphs removes the US since the graph gets scaled excessively.

We can see that 3 of the bottom 5 deficit countries have been in deficit since 2000: Canada, the US and the UK (Saudi Arabia went from having one of the highest trade surpluses to one of the highest deficits almost purely due to the falling oil prices)

And on the other end, all of the top five surplus countries have been in surplus since the turn of the millennium. Germany and China alone have a trade surplus of half a trillion dollars.

The putative goal of the bancor system is not to punish successful exporters, but to push importers from spending funds on consumption to spending funds on investment (whether this is true remains to be seen), or in other words, to ensure the competitiveness of deficit countries.

Keynes actually pushed the British delegation to adopt bancor as their official position in the Bretton Woods conference – the same conference that led to the creation of the IMF and World Bank. However, American delegates objected to Keynes’ measures.

After all, the US, coming out of the war as a surplus country, thought it was a clear loser in such an arrangement. Not only would they be forced to give loans on their excess reserves, they would be charged a negative interest rate for it! But now the US is paying the price for their initial skepticism. Due to the Triffin dilemma, the US, providing the world’s reserve currency, is now perennially a deficit country (the US was last a surplus country in 1975).

Had the US accepted this system years ago in the Bretton Woods conference, it would have probably been a trade neutral country, instead of it being in perpetual deficit.

Indeed, if bancor were implemented, export-promoting countries like China would have no incentive to devalue their currency. In fact, this might be one reason the Chinese finance minister argued for bancor. He might have been anticipating the decline of China’s manufacturing industry, or the steady rise in the renminbi’s international status.

Another benefit of this would be the curtailing of the “global savings glut” that former Fed Chairman Ben Bernanke warned of back in 2005. While savings gluts are not necessarily harmful, surplus countries may fund risky financial assets, as they, now infamously, did in with residential mortgage-backed securities in the run up to the 2007-2008 financial crisis.

Of course, for the system to work effectively, it would require proper and honest accounting. We saw how difficult this can be to achieve in practice, when Greece and others dishonestly reported lower levels of debt to the EU. And this problem is compounded as both deficit and surplus nations would have incentives to post fraudulent figures.

And another risk is that countries may reduce trade with one another, since the benefits of accruing a trade surplus are eradicated. And a fall in global trade would lead to certain negative effects, such as the fact that non-trading countries are much more likely to declare war on one another than trading partners.

Yet, if countries are truly dedicated to eradicating excess deficits, they would be wise to listen to Keynes’ lost idea. Who knows, if bancor prevailed, we might have seen “made in the USA” everywhere instead of “made in China”.