President Trump’s June 21st rally in Cedar Rapids, Iowa was predictably similar to previous rallies he gave as a candidate and continues to give as President. He bragged about the size of the crowd filling the “big, big arena,” reiterated his promise to build a wall on our southern border and blasted Democrats at every chance.

What set apart Trump’s visit to Cedar Rapids, six months and one day after his inauguration, was that it was his first to a state west of the Mississippi River as President. Trump made seven separate visits to his Mar-a-Lago club in Florida before his first trip West. As of September, he had made just six planned stops in the West, excluding his trips to the Gulf Coast in the wake of Hurricane Harvey. Despite riding the support of so-called “Middle America” to the office where he now sits, since taking office Trump has remained largely siloed in the same region where he was born, educated and built his business empire.

That the western states aren’t well-represented in national electoral politics seems on its face to be a minor grievance relative to the issue of traditional racial and gender exclusivity in our presidential history. However, the division of our nation into regions starkly separate in culture — reinforced by lack of proper representation and outreach — is a fundamental cause of the partisan polarization responsible for the poisonous politics of our time.

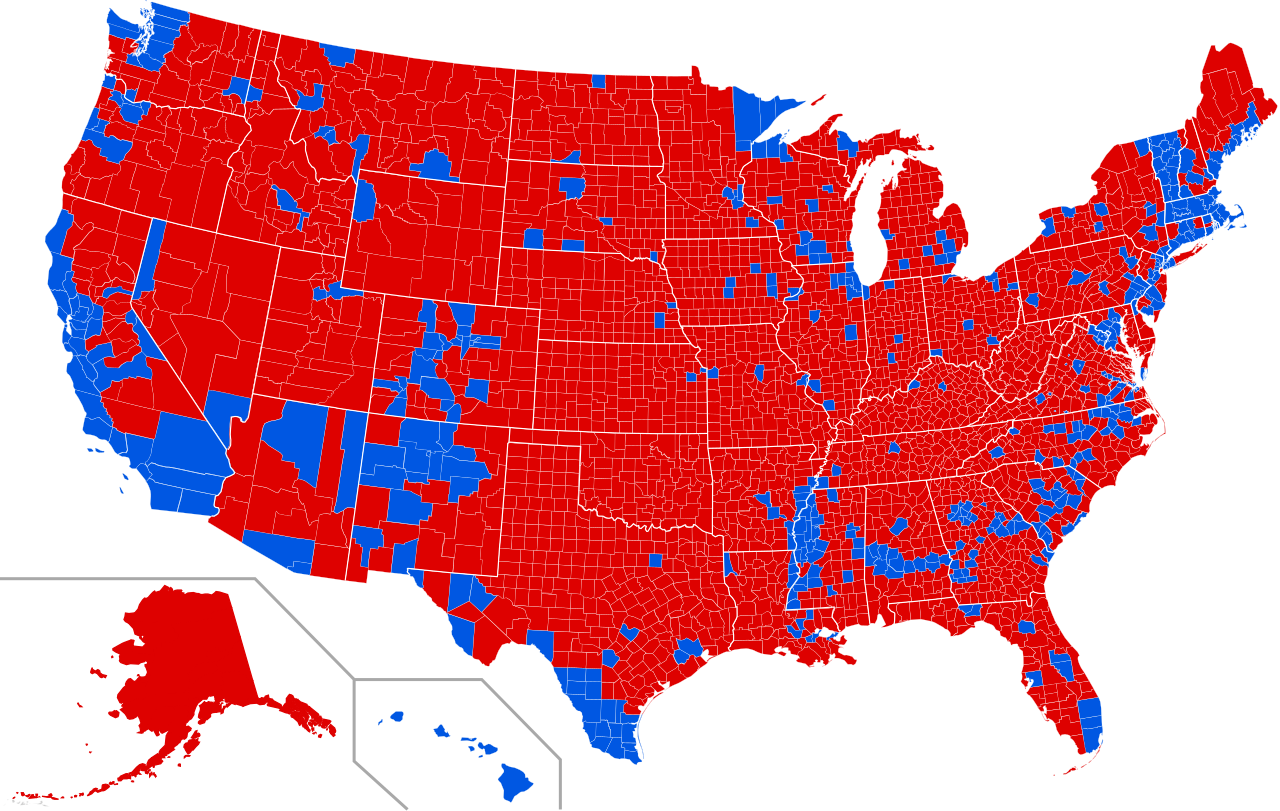

After the 2016 election, narratives that the Democrats’ loss was a direct result of “Blue America” being out of touch with “Red America” were abound. At best, this claim is a half-truth, one piggybacking off the electoral college’s result to absolve Red America’s similar lack of outreach and desire to empathize with the other side. Had the electoral college flipped the other way, there is no doubt we would have witnessed the opposite claim. No matter the result, an understanding of the issue as a two-way street is lost.

In a March piece published by New Republic, writer Kevin Baker argues for a “Bluexit,” a brand of “New Federalism” where blue states give up any regard of legitimacy for any state where even 51 percent of voters might have chosen Trump. The structural political changes Baker argues for — blue states being able to provide the entirety of the modern progressive platform for themselves with no help from the Federal tax base — are beyond pie-in-the-sky. But the entire premise of the “Bluexit” is ultimately more pernicious. Baker isn’t the only pundit to proclaim 2016 a point of no return for our cultural and regional differences as beyond reconcilable, although he does manage an unrivaled level of antagonism — comparing Trump states to “crazy, deadbeat in-laws,” the removal of whom is the “good part of a divorce” — in doing so.

Trying to bridge our divisions is not only possible, it remains worth doing so because our already bitter political situation will continue to escalate dangerously if we don’t. When an entire region of voters is underrepresented among the major parties and ignored once a candidate has reaped their electoral votes, it’s likely to make these voters susceptible to demagoguery and strongman figures on the left and right who float extravagant, unrealistic policies. It’s also a root source of the attack politics characterizing our time. Opportunistic politicians of both parties capitalize on the regional ignorance of the other side, convincing voters that the other ignores them out of pure contempt. This fuels the “us versus them” mentality contributing to vile election cycles like the 2016 presidential race.

The partisan polarization which consistently grinds our legislative branch to a halt is the end to the means of perpetuating this mentality. At the root of our polarized politics is a negative partisanship — people vote and mobilize out of fear for the other side rather than a strong support of anything in particular. One only needs to listen to speeches at the major party conventions in summer 2016 to see this in practice — here are two reasons to vote for us, and three reasons not to vote for the other. It’s no surprise, then, that in a two-party system representing a country divided culturally in half, we find ourselves in a moment of such political dysfunction. Those who feel it is a good time to give up say so only because they aren’t prepared to look within themselves for a solution.

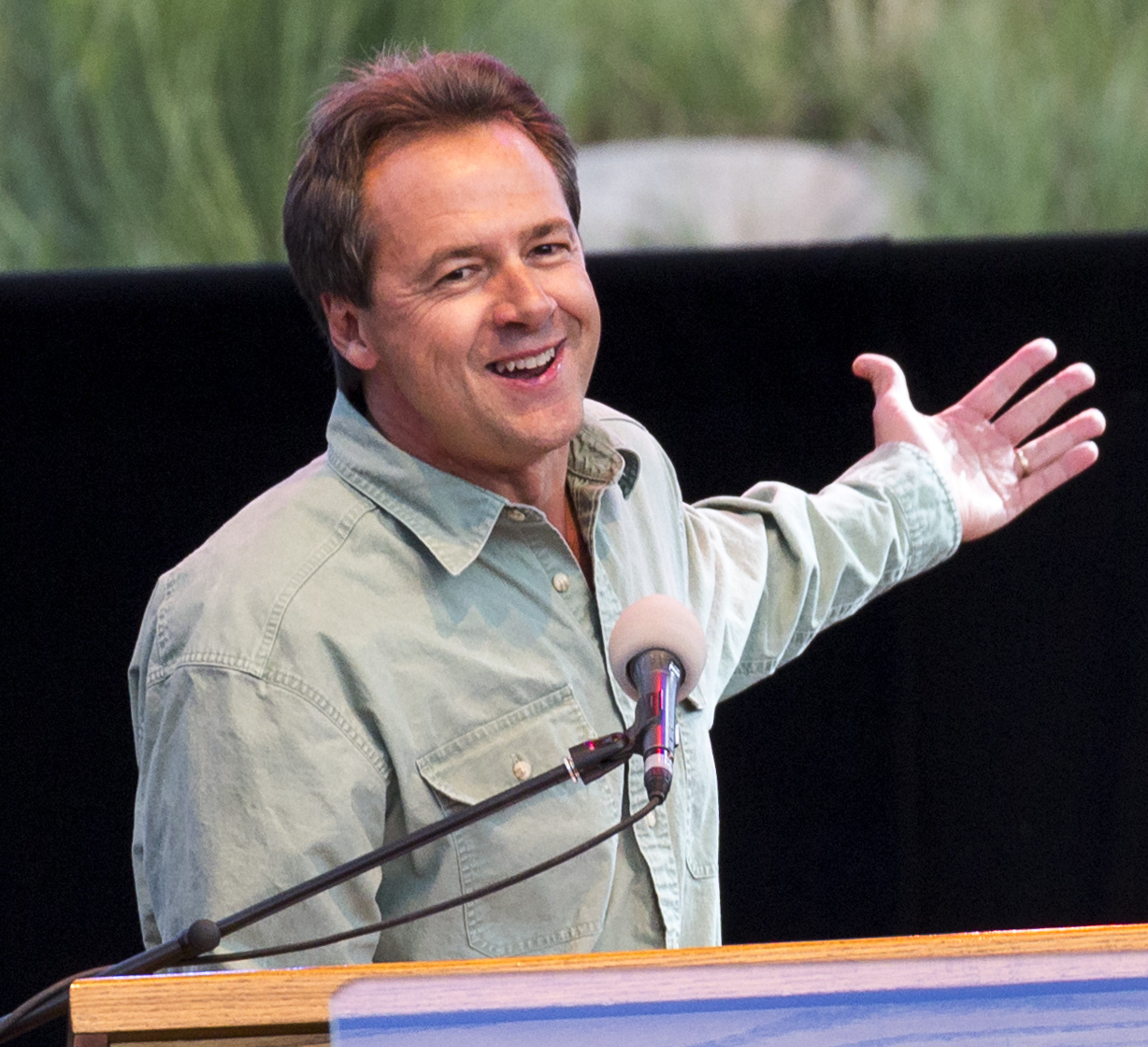

In a May 5 Op-Ed in the New York Times, “How Democrats Can Win in the West,” Montana’s Democratic governor Steve Bullock addressed the constant bombardment of questions regarding how a progressive can win a statewide race in a place easily carried by Trump. In today’s polarized time, one might assume such a feat requires a complex political strategy, favorable luck, or both. The prescription Bullock gives, however, is nothing of the sort. His one big secret? Talking to people. Bullock describes speaking at events filled almost entirely with people who disagree with him politically. Events like these are almost never held at the national level by either party because of the data-driven approach to campaigning emphasizing turning out supporters rather than changing minds. This strategy makes sense in theory but results in candidates ignoring or even lashing out at the supporters of opposing candidates. And when the base of voters taken for granted in the data-driven models turns out a lower rate, no new voters have been convinced to replace them.

This type of outreach also forces a politician to take on a genuine message of unity. If a candidates speaks about national unity one minute and labels the supporters of their political opponent “deplorables” the next, voters will see the unifying message as hollow and phony. Speaking to those voters who might generally disagree forces a type of political messaging that reconciles policy differences in a more productive fashion than over-generalized attacks. After 2016, it became clear that a realignment of party messaging was desperately needed by the Democrats. Taking a page out of Bullock’s book on the issue of voter outreach would be a good start — and there’s a reason Bullock’s name has been floated as a potential 2020 candidate.

Either as a function of our current divisions or of the nature of democratic government itself, politicians are slow to change. Along with necessary changes in the public sector, there are private entities that will also bear some responsibilities if Americans are going to bridge our regional divisions. If people are influenced by real life experiences in engaging with people who may think differently from them, they will no longer put up with ineffective and divisive politicians and will let them know at the ballot box.

A striking example is Silicon Valley — which deserves significant blame in the packing of college-educated liberals into our coasts. Amazon’s search for a second headquarters is a prime opportunity to move the precedent away from California and New York as options 1a and 1b for major tech firms. Dallas, Austin and Kansas City are the only non-coastal cities West of the Mississippi that are reportedly vying to land Amazon. The selection of any of those cities would be a revolutionary change in the tech industry, one that would hopefully inspire similar companies to consider putting down their roots in communities more politically diverse than New York City or the San Francisco Bay Area. Doing so would ensure that private individuals with different backgrounds are given the same chance to have the type of conversations advocated for by Bullock.

Such conversations, whether in the public or private sphere, won’t be easy. But that guarantees them to be worth having. Failing to do so would represent, as Kevin Baker calls it the abandonment of the “American national enterprise.” While that’s precisely what he and others now advocate for, we’ve come much too far in that national enterprise to give up now.