In Africa’s southern states, land remains a deeply emotive issue, an open wound harkening back to days of apartheid and colonialism. In post-apartheid South Africa, it is estimated whites own 67% of the land (while they are 8% of its population). In a survey run by American political scientist James Gibson, two-thirds of black South Africans agreed with the statement, “Land must be returned to blacks in South Africa, no matter what the consequences are for the current owners and for political stability in the country.” Such is the urgency that the African National Congress (ANC), the ruling party of South Africa for the past twenty-five years, and its newly-elected head, Cyril Ramaphosa, declared his support for a constitutional amendment to allow land expropriation without compensation.

Whether Ramaphosa and the ANC are doing so genuinely or for political gain, two decades on from apartheid, there is much appetite for correcting not only the political imbalances of the colonial-apartheid system, but also its economic inequalities.

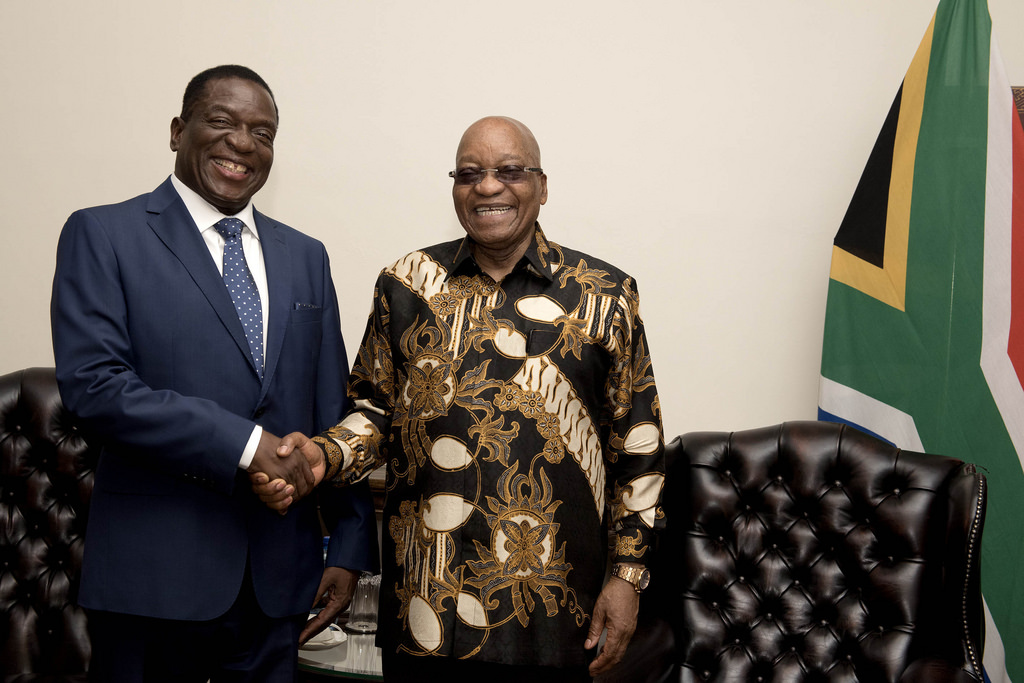

South Africa’s northeast neighbor, Zimbabwe, has already undergone land reform, attracting much international attention in the process. The bulk of land reform was complete before Robert Mugabe—Zimbabwe’s strongman ruler for the past 37 years—was unexpectedly deposed in late 2017 to make way for another strongman, Emmerson Mnangagwa.

Back in the 80s and 90s, Mugabe supported the “gradual” transition of land, where land would be transferred from a willing seller to a willing buyer, with the British government subsidizing part of the costs. However, as funds from the British government dried up, groups in Zimbabwe, especially veterans, grew frustrated with the pace of transfers and decided to take matters in their own hands, sometimes by means of violence. Mugabe, whose support was freefalling due to widespread economic mismanagement, promoted (or at least did nothing to stem) the appropriations.

While Mnangagwa has very close ties to ZANU-PF and the army, a natural question is whether Mnangagwa will significantly alter his predecessor’s approach towards land, quite possibly the most important issue in post-independence Zimbabwean’s politics.

Teasing out the effects of the land reform, especially when it kicked into high gear in the 2000s, is not straightforward. This is understandable; given weak global demand, droughts and hyperinflation, efforts to isolate cause and effect are hampered. The formal economy in this period teetered on the verge of collapse, so obviously farming output would be negatively impacted regardless of whether land reform occurred or not.

Yet some have tried to do so. The Research and Advocacy Unit in Zimbabwe released a comprehensive paper, arguing that the land reform was an utter failure, pointing to the massive decrease in agricultural output succeeding the appropriation years, especially in export-oriented crops. Charles Laurie impressively documented the violence and hectoring accompanying the appropriations, on his website and in his provocatively-titled book The Land Reform Deception. Finally, nepotism corrupted the whole process, as civil servants and government officials got a disproportionate amount of land, some of whom are now indistinguishable from colonial-era white farmers (the Mugabes themselves were reputed to have owned 20 farms!).

However, a wave of new scholarship is challenging these melancholic conclusions, which are often parroted uncritically by foreign media. While nepotism was undeniably an issue, 80% of those who received land during this period were “ordinary” Zimbabweans (meaning they were not part of the civil service nor the military).

Furthermore, while large-scale export-crop farming has irrefutably been devastated, staple crops have rebounded to pre-appropriation levels (and even to pre-independence levels). Maize production is now at 2100 tons, the highest it has been for two decades, and approaching the all-time high of 2900 tons produced in 1984. Perhaps this switch from plantation to peasant crops is a manifestation of the elusive “pro-poor” growth, one of development economics’ most enduring buzzwords. Even during economic chaos, land reform has turned out to be an unemployment killer, through the labor-intensive nature of the work. Researchers Hanlon, Manjengwa and Smart estimated in their book that 550,000 family members and 350,000 paid workers now work on land that was previously tilled by only 170,000.

What is Mnangagwa’s view of all this?

At first glance, it seems as if Mnangagwa’s reconciliatory tone is markedly different from Mugabe’s. Judging from his inauguration, Mnangagwa is more critical of the land appropriations and declared his commitment to compensation. In the speech, he said, “My Government is committed to compensating those farmers from whom land was taken.”

And Mnangagwa is not all talk, as he has flexed his muscles, perhaps in a bid to impress foreign investors. His agriculture minister ordered “illegal settlers to vacate farms”. And headlines around the world waxed lyrical about the return of the lands of the white farmer Robert Smart. (Noteworthy is the photo of apartheid Rhodesian leader Ian Smith on Smart’s wall!)

At the same time, we must always keep in mind that Mnangagwa is, was, and always will be a ZANU-PF partisan. Whatever the tone, what Mnangagwa said was, at least technically, the Constitutional and Mugabe’s position.

And of course, this is not to mean a return to the past is politically feasible. In his inauguration, Mnangagwa said, “Dispossession of our ancestral land was the fundamental reason for waging the liberation struggle. It would be a betrayal of the brave men and women who sacrificed their lives in our liberation struggle if we were to reverse the gains we have made in reclaiming our land.”

This hints at a “middle-ground” approach, one where correcting colonial imbalances is sought, but in tandem with a commitment to compensating those displaced. This may be the closest to an ideal solution anyone will ever get.

Even not taking to account politics, it seems that if land reform were to be abandoned, an opportunity for the economy to be transformed from the control of a few to the rural masses would be missed. As Sam Moyo noted in a 1998 UNDP report, only 300 farmers owned three million hectares of arable Zimbabwean land. And agriculture economists Michael Roth and John Bruce estimated in 1994 at least 40-50% of arable land was underutilized, rising to 85% in some regions.

Perhaps in line with its pro-capitalist, anti-landholding heritage, The Economist recently published an article noting the importance of land reform in breaking the stranglehold of landed elites, incentivizing rural farmers to produce, and therefore unlocking long-term growth. They argue this was a key reason for the success of the Asian Tigers, like Taiwan, South Korea and Japan. If it worked for the Asian Tigers, why not for an “African Leopard”?

While Mnangagwa’s openness to the outside world is welcome, Zimbabwean decision makers should be skeptical of claims that agri-business is necessarily more modern and better than small and medium-sized farms. At this point in time there is no clear economic consensus on the optimum size of farms. Therefore, what is important for Mnangagwa to do is, one, to continue his promising rapprochement with white farmers, and, two, to transform the state apparatus into a positive force – when it was– when it was previously effective only in making life harder for farmers, through corruption and price controls. Indeed, white farmers reached their impressive levels of production with the assistance of the British colonial government.

Furthermore, productivity in the Mugabe era was stunted, because of a dearth of both physical and human capital. Mnangagwa has shown some promise in this regard. In a bid to ease the well-known financial woes of some farmers, Zimbabwe’s cabinet approved an eye-catching 99-year lease plan for agricultural inputs. And the relative success of the “Command Agriculture” program, championed by Mnangagwa when he was vice-president, hints at a possible scaling-up. However, as always, it must be ensured corruption is controlled as much as possible, as it frustrates the implementation of even the most elaborate of plans. A notorious example was the Reserve Bank of Zimbabwe’s plan to distribute equipment such as tractors and plows. According to 2007 statistics released by the Bank itself, 50% of these goods were distributed to top government ministers. To Mnangagwa’s credit, a recent article reporting the arrest of two individuals for embezzling agricultural inputs could be reason for tentative optimism in this regard.

Finally, simply not blowing up the economy may very well provide the biggest assistance to farmers (this is not a completely facetious statement). As the researchers Marleen Dekker & Bill Kinsey argued, postcolonial Zimbabwean history reveals the macroeconomic context matters greatly for the development of smallholder agriculture. Furthermore, Scoones et. al reveal evidence that some farmers deliberately left land unused because of the adverse macroeconomic environment. And the urge to implement ill-advised, quick fixes must be restrained. For example, the price controls imposed on fertilizer in the 2000s only reduced their supply and hence usage.

Mnangagwa does not have to take the ANC’s non-compensation approach, and redressing displaced white farmers is not antithetical to genuine land reform. Furthermore, redress can signal that the drawn-out tensions of yesteryear are defusing (the international investors Mnangagwa wants to woo will take notice). Stemming appropriations can also give farmers, big or small, peace of mind that government, or other groups, will not arbitrarily evict them.

As Mahmoud Mamdani noted, after Idi Amin had infamously expelled from Uganda ethnic South Asians, who formed part of the commercial middle-classes, many indigenous Africans thought a window into wealth and opportunity opened for them. Instead, African peasants themselves became the victims, as Amin’s 1975 land decree reform took away legal recognition of land, and appropriated customary land that was not being “productively used”. Therefore, all sides will be more likely to invest for the long-term if the land appropriations are restrained.

Of course, there are concerns to be had with grandiose populist claims. And a desire to lift sanctions, as well as creating a stable macroeconomic environment is important. Yet Mnangagwa must not abandon land reform. If he continues to make the right decisions, Zimbabwe can be an unlikely model of how an equitable rural base can spur the engines of development.