On Sunday, March 4th 2018, 46 million Italians voted to form the country’s 18th legislature and for the succession to a new government. The new administration is likely to affect Italy’s position within the European Union and the Eurozone, Italexit being a topic of fierce debate domestically. Many Italians are frustrated by the lack of legitimacy and representation they feel within the European Parliament. Most of the parties that ran in this election reflected popular opinion, with several taking strong eurosceptic positions and others being clearly pro-Europe. The election results – which led to a hung parliament with no clear majority and more recently a constitutional crisis – have given the so-called anti-EU parties a large share of the seats in both the Chamber of Deputies and the Senate. Nevertheless, it is clear that an Italian exit from the EU is not foreseeable. The wave of hesitation which took over euroskeptic parties, and President Sergio Mattarella’s decision to block the new government are deeply rooted in a pro-European commitment.

The three largest groups in Parliament after the election are the center-left coalition, the center-right coalition, and the Movimento 5 Stelle (Five Star Movement – M5S). The center-left coalition is comprised of four parties; the Partito Democratico (Democratic Party – PD) led by Matteo Renzi has the most voter support and was in power during the previous term. The center-right coalition is also made up of four parties, including Silvio Berlusconi’s Forza Italia (Go Italy) and Matteo Salvini’s extreme right La Lega (The League). Lastly, Luigi Di Maio’s Movimento 5 Stelle (Five Star Movement – M5S) is an “anti-establishment” movement advocating for leftist and rightist elements such as a universal basic income and the elimination of 400 “useless” laws.

As has been the case in the previous Italian elections, results of the most recent iteration thereof are ambiguous to say the least. There is no party with a clear majority; the party with the largest share of seats (32 percent) is the Movimento 5 Stelle. However, the center-right coalition received 35 percent of votes, thus controlling a larger portion of the parliament than the Movimento 5 Stelle. The main problem is that neither of these blocs have majority representation, making it extremely difficult to form a new government and appoint a Prime Minister.

The two “winning” parties are the Movimento 5 Stelle and La Lega. The Lega received the largest share of votes in the center-right coalition, as well as the third largest portion of votes absolutely (third to the Movimento 5 Stelle and the Partito Democratico). These two parties are deemed to have won because the center-left coalition (including the PD) received only 23% of votes (although PD received more votes than Salvini’s party only). Thus, the Lega and M5S lead the two largest groups in parliament. Given these circumstances, it is President Mattarella’s job to construct a new government by hearing out all sides and trying to find a common ground, which has proven to be rather challenging.

The two “winning” parties – Movimento 5 Stelle and La Lega – have frequently expressed elements of Euroscepticism and the intention to push for an EU membership referendum. The Movimento 5 Stelle has repeatedly “stated in the past that it would like to hold a referendum on Eurozone membership, something Di Maio previously echoed.” The Lega has consistently been a strongly eurosceptic party, and Salvini threatened to trigger an “Italexit” if he were to become Prime Minister. He explains that Italian autonomy would shield the country from the EU’s “unfair” financial laws, and has criticized calls for greater integration into the EU and the Euro itself (which he renamed “a German currency”). Berlusconi, the leader of the second largest party in the center-right coalition, Forza Italia, is also critical of Italy’s position within the EU. In comparison to Salvini, however, he holds a more balanced view and demands a greater role for Italy in the EU, rather than a radical exit. On the other hand, the center-left coalition led by Renzi is not opposed to the EU and has been accused by the Movimento 5 Stelle of being “Italy’s most establishment party.”

Surprisingly, the two eurosceptic parties have recently “toned down their rhetoric on the topic and do not advocate an immediate Euro exit referendum anymore, in order to appeal to centrist voters.” In the month before the elections Di Maio’s rhetoric took a dramatic turn: he claimed that “we need to renegotiate some EU rules, but not in an in/out referendum,” and claimed that he believed Brexit had “weakened” the EU. In February, Di Maio called the EU Italy’s “home.” More recently, Di Maio reiterated this stance by saying that Italy will leave neither the EU nor NATO. On Tuesday March 13th, in Strasbourg at the European Parliament, Salvini claimed that an exit from the Euro is currently “impossible” for Italy, although his government would ignore the 3 percent inflation roof if needed and that he “hopes that the Italian vote will prove to be an initial taste in other countries.”

The Lega and the Movimento 5 Stelle took two months to negotiate a government plan, which they presented to President Mattarella on May 23rd. The plan, which appoints law professor Giuseppe Conte as Prime Minister, called for “reducing the country’s public debt through growth measures that would boost deficit instead of fiscal discipline favored by the EU. The program calls for the “renegotiation of EU treaties and the main EU regulatory framework” as well as a review of the EU economic governance system.” The markets responded to this plan negatively, as the anti-establishment coalition and their plan was seen as threatening to the EU balance and sovereignty.

The most shocking development of the last few months was President Mattarella’s decision to block the new government proposal brought forth by the Movimento 5 Stelle and the Lega. The government proposal included the list of Ministers for the various Italian Ministries. Mattarella vetoed the government proposal because Paolo Savona – the economist nominated for the role of Finance Minister – has a history of expressing anti-Euro sentiments. Savona had once said that “Italy was mistaken to join the single currency.” Mattarella is afraid that appointing Savona as Finance Minister would portray an Italian intention to leave the EU or the Eurozone – something he strongly opposes.

On Thursday May 31st, Luigi Di Maio and Matteo Salvini presented a new government proposal which was finally approved by President Mattarella. This time, eurosceptic Paolo Savona was ironically nominated for the position of Minister of European Affairs. The Finance Minister will be political economy professor Giovanni Tria, who is only critical of the Euro’s strict policy of fixed exchange rates. His view with regards to the Euro is more balanced than that of Savona because he is critical of the functioning of the Euro, and of Germany’s role, rather than being critical of the entire monetary system.

Italexit is unlikely given the clear pro-European stance of the President, and the decreased commitment of the Movimento 5 Stelle and the Lega. A more likely development is that Italy demand for reform in the European Central Bank – a demand which is also supported by several European countries including Greece and Spain. Nevertheless, the President’s recent veto may rouse increased anti-Euro sentiment due to its interpretation as a prioritization of the EU’s demands over Italian demands and local democratic processes. For example, Di Maio had called for impeachment and for new elections after Mattarella’s veto.

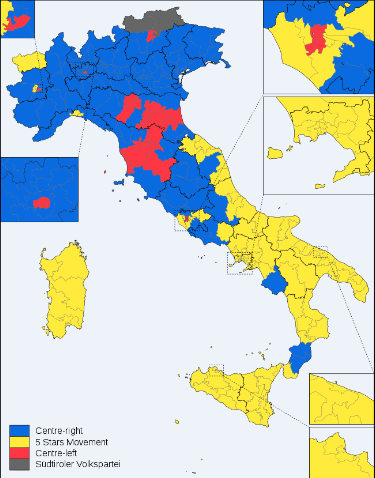

Photo: Italian 2018 elections Chamber of Deputies Constituencies