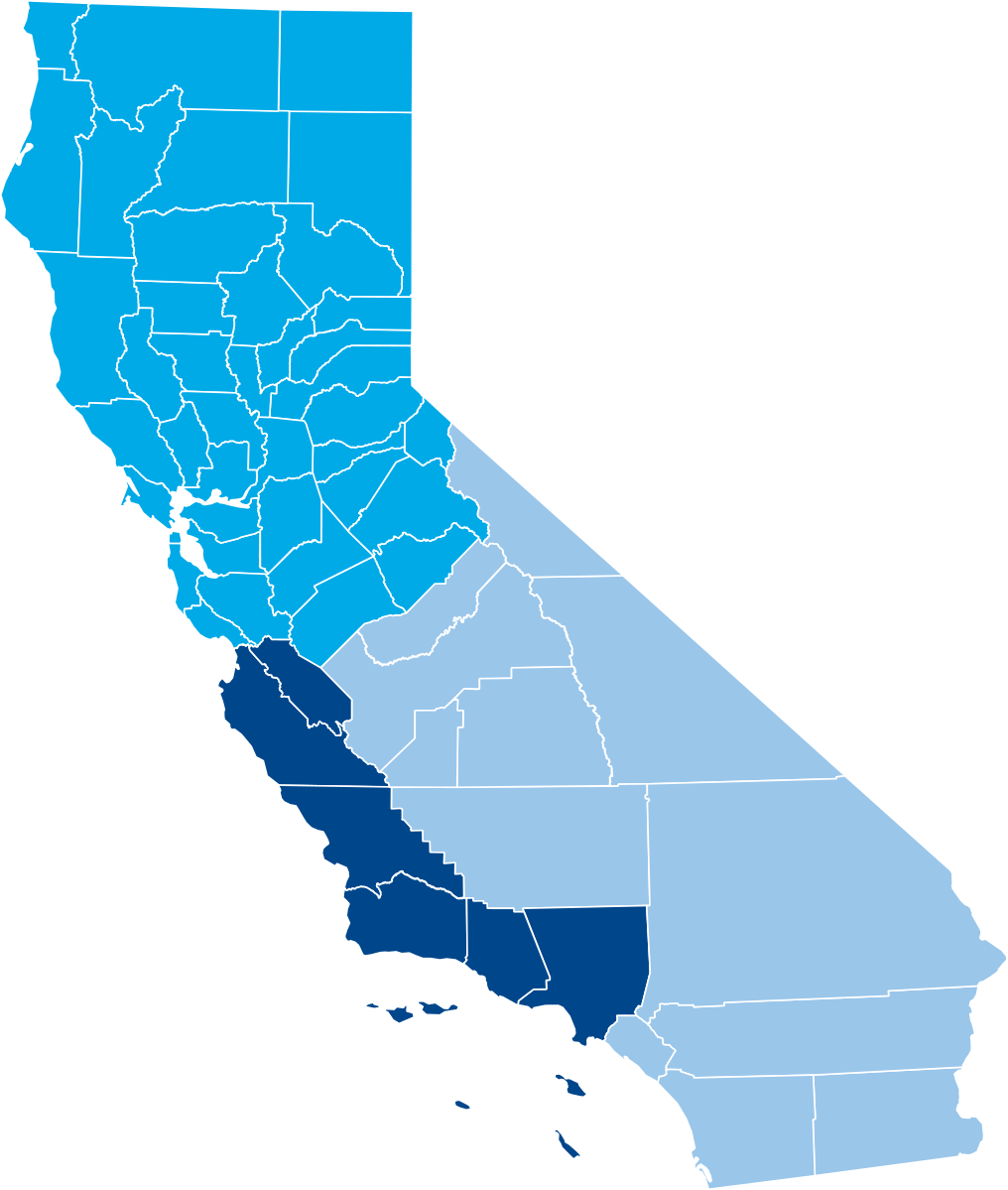

In October 2018, a referendum to split California into three states almost made it onto the state ballot, gathering more than 600,000 signatures. It would have created three new states: “Northern California” (stretching from the Oregon border to Sacramento), “Southern California” (extending from the Mexican border to Fresno), and “California” (located along the coast from Los Angeles to Monterey). The referendum was proposed and funded by tech billionaire Tim Draper, who has chosen this issue as his own personal project and caused a stir in California politics.

The Supreme Court of California struck the initiative from the ballot soon after it was submitted pending further review. Proponents of the initiative were trying to bypass the need for approval from the state legislature, the constitutionality of which is uncertain. But the measure could return in 2020, this time approved under the constitution. The referendum also faced political barriers: it would have needed approval not only from California voters, but also both houses of Congress, a daunting political obstacle.

But even though the proposal failed to make the ballot this time, with the proper implementation, such an initiative could be exactly what California needs. And as the world’s fifth-largest economy, California is critical to the fate of the nation as a whole. At the very least, the idea deserves to be taken seriously, because the state’s current unequal representation, high taxes, and poor infrastructure stem from inherent difficulties in governing a state as vast and extremely diverse as California. Partition movements such as this one maintain that those problems can be better managed by smaller state governments, which would respond to their regions’ particular needs and represent their people more effectively.

The “Cal 3” proposal is not without precedent; the nation’s most populous state has a long history of partition movements. 27 significant proposals for splitting up the state have been made since its creation in 1850. One proposal in 1859 even passed both the State Assembly and Senate, but the outbreak of the Civil War distracted Congress from putting it up to a vote.

Today, a common claim among these movements is that the densely-populated areas of Silicon Valley and greater Los Angeles override the rest of the state’s voices, resulting in little representation dedicated to areas away from the coasts. The 31st state is simply too large to govern effectively as it is now. Of course, Texas is geographically larger and remains united, but Texas has 10 million fewer people than California. What is more, California is still growing by 300,000 people per year, according to the Census Bureau. The state is extremely diverse geographically, culturally, and politically, and this makes governing it as a single unit very difficult.

One symptom of those difficulties is that taxes in the Golden State are some of the highest in the nation, with sales and income taxes significantly higher than the national average. Much of this is due to Proposition 13, the controversial 1978 referendum that locks property taxes at 1% and doesn’t adjust them as property value rises. The justification behind it was that real estate prices in regions such as San Francisco rise quickly, so homeowners need low property taxes to stay afloat. Though well-intentioned, Prop 13 has led to many unintended consequences for less-affluent regions.

Because Prop 13 has lost the state tens of billions of dollars in revenue, Sacramento has been forced to recoup that revenue with much higher gas, sales, and corporate taxes. California is now one of the most heavily taxed states in the nation. But these taxes also apply to the poorer counties in the north and southeast, whose low real estate prices mean that people don’t reap the rewards of Prop 13 as much. It’s far more difficult for the average Fresno resident to pay $3.50 a gallon for gas than it is for a San Franciscan. Through these high taxes, poorer counties with fewer homeowners end up paying for the artificially low property taxes of wealthier counties and businesses. But lawmakers have by and large refused to touch the subject of reforming Prop 13, exemplifying that in such a large state, the wealthier voices can drown out the rest.

If the state were to split into three, each region could decide for itself whether Prop 13 is worth it. If the new California (which would include Los Angeles) decided to prevent businesses from claiming protection under Prop 13, for example, it would no longer have to indirectly subsidize the LA Country Club by $89.9 million per year. Meanwhile, Northern California could keep the measure to give San Francisco small businesses a chance.

Another example of California’s size caused issues is that the state still has the second-lowest infrastructure rating in the country (despite the enormous gas taxes). This is mainly due to the difficulties of managing 50,000 miles of roads and enormous public transportation systems across a state of over 30 million people. The state auditor recently accused the Department of Transportation of large amounts of waste and bureaucratic inefficiency throughout the department, and the pure size of its backlog shows why. Over 15,000 miles of California highways are currently in need of repair. Splitting up the state would bring wasteful departments like Caltrans back under control, as each new department would have a manageable task burden. The same goes for the Department of Education, the Department of Corrections and Rehabilitation, the state EPA, and so on and so forth.

Of course, dividing a state isn’t as simple as a yes/no vote. The administrative tasks associated would take years to complete, and new problems would undoubtedly crop up once they were completed. Los Angeles residents, for example, might resent having to pay out-of-state tuition to attend the University of California, Berkeley. And water distribution from the north to the south would indoubtedly be even more complicated than it is now. But these problems also carry their own solutions: more out-of-state students would mean less of a gap between in-state and out-of-state tuition, and existing water distribution infrastructure need not be changed even if it were to cross new state lines. Just because California would be divided doesn’t mean it could no longer work together. Issues might arise from splitting the state, but we cannot know how problematic those issues would be if there is no dialogue in the first place.

Inefficiencies and inadequacies in California’s state government could be listed ad nauseam. They range from overcrowded state prisons to lack of affordable housing to poor environmental regulation and beyond. These problems are inherent in any state as large and diverse as California, and they will remain–and likely worsen–as long as it stays in one piece. But the real value to partitioning California isn’t just in short-term issues like Prop 13 or Caltrans; these are just current examples of state government stretched too thin. The real value of a split lies in similar problems of the future that will be more easily dealt with by smaller, more responsive, and more representative state governments.

The longer we postpone this issue, the more California will grow and the worse the problem will become. And none of this even goes to mention the fact that all 40 million Californians are represented by only two U.S. senators. America needs to take this seriously and start not only a statewide dialogue on partitioning but a nationwide dialogue as well because ultimately the fate of this movement is in the hands of Congress. The future of California is too important to entrust to a single large, inefficient, and unrepresentative state.

Image: “Cal3 Map”