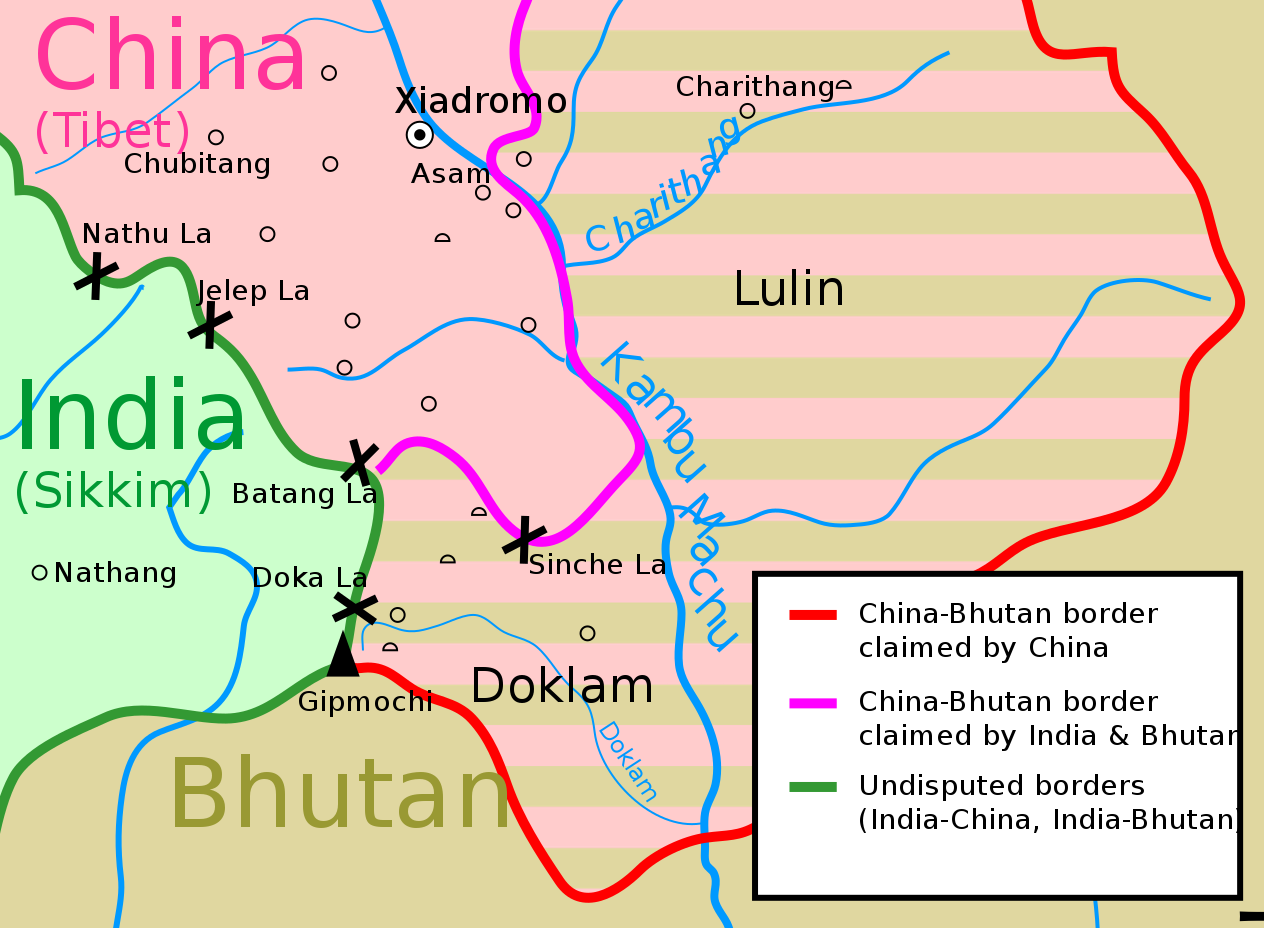

In the summer of 2017, China and India engaged in a 73-day border standoff on the Doklam Plateau, a 34 square mile piece of land disputed by China and the region’s smallest country, Bhutan. Doklam is located near Bhutan’s mountainous southwest (Ha), edging up to the border trijunction with India (Sikkim) and China (Tibet). The standoff occurred after Indian forces discovered the Chinese army building roads into the plateau. In keeping with a half-century tradition of Indo-Bhutanese cooperation, including Indian road-building in Bhutan, the Indian army advanced past Indian borders and stopped the construction. India’s stance indicates more ongoing fears of Chinese incursion than concern for Bhutanese territorial integrity. Like Nepal, Bhutan is a vulnerable buffer between two giants—China and India—and must navigate Indian military and economic aid, Chinese diplomacy, and its own sovereignty. With no choice but to be stuck in the middle of a continental battle, Bhutan must decide what role to play and whose overtures to accept. At the heart of the struggle are the borders and the roads built to overcome them.

Why would two global superpowers risk themselves over a tiny, remote patch of the Himalayas? Although Doklam is small and mostly uninhabited, it sits above India’s narrow Siliguri Corridor, the so-called Chicken’s Neck connecting the majority of India to the North Eastern Region (NER). Just 17 kilometers wide at one point, the Siliguri has long been subject to security concerns, particularly regarding its smuggling operations, insurrectionist groups, and Bangladesh border. Doklam is critically close to the border trijunction. As shown by satellite imagery, China has long built roads into the plateau. Unfortunately, the remoteness of the region creates an unclear timeline, with estimates of construction ranging from the late 1980s to the mid 2000s. Most notable is the 2005 (or earlier) road that lies just 68 meters from the Indian Doklam (Doka La) border post. Though this road is in eyesight of Indian soldiers, the situation remained fairly inactive until recently. It was this road that China sought to extend, possibly towards the Bhutanese Zompelri army camp about a kilometer away. The camp is located on the Zompelri (Jampheri) ridge, overlooking the Siliguri Coridor so closely that “you can see the glow of Siliguri’s lights.” Thus, China’s actions point not toward an interest in the Himalayan plateau but rather to what lies below it: trade routes and more disputed lands.

Bhutan’s position in the Sino-Indian struggle dates back to the 1961 beginning of Indian-funded Five Year Plans (FYPs) and the 1962 Sino-Indian War. After invading Tibet, China continued to push its Himalayan boundaries. India did too, but politically and economically. As border tensions mounted, Bhutan’s position as a buffer between China and India became increasingly clear, particularly in the 1949 agreement that has allowed India to guide Bhutan’s foreign policy. India further capitalized on its relationship with Bhutan by taking an active role in Bhutanese economic development.

In the last half century, India has shaped much of Bhutanese development through aid and trade, tying infrastructure to Himalayan border affairs. Delhi fully funded Bhutan’s first two FYPs, the cornerstone of their infrastructure-focused sustainable development program. A vital part of the FYPs, the Indian Army’s Border Roads Organisation (BRO) runs Project Dantak, a road-building project connecting key Bhutanese towns to the Indian border. While Dantak has been vital to trade, it is primarily a means of defensive access for India. India and Bhutan respectively hold two and three disputed areas with China, Doklam included, and if the situations escalate, Dantak’s roads would allow for army mobilization.

While India’s influence has continued in recent decades, Bhutan has asserted more independence—to an extent. Dantak has continued to shape Bhutan with its infrastructure, creating a visible manifestation of Indian influence. As the Five Year Plans have grown in size, their funding has diversified to include other international donors, while India contributes an estimated 14.56 percent to the current 12th FYP (2018-2023). In a mark of economic self-sufficiency, Bhutan is funding 80.05 percent of its FYP. On the diplomatic front, Bhutan has asserted itself with the 2007 renegotiation of the 1949 treaty, giving it freedom to control its foreign policy while retaining Indian friendship. However, India’s active role in the Doklam standoff has reaffirmed Indo-Bhutanese cooperation and shared vulnerability.

While Bhutan has gained more agency in its relationship with India, China has sought to increase its influence. In August 2017, China and India agreed to disengage without settling the borders. Instead of a return to the region’s prior uneasy coexistence, engagement increased with a Chinese economic and militaristic push toward Bhutan. In July 2018, a Chinese delegation visited Bhutan to continue border talks and invite Bhutan into China’s Belt and Road Initiative (BRI). While India’s BRO focuses on its smaller neighbors, China’s BRI spans three continents and 65 countries. Bhutan’s inclusion would symbolize not only closer Chinese relations but integration into a global trade network. This might make Bhutan less dependent on India (which accounted for 82 percent of Bhutanese bilateral trade in 2017), but would put it under the influence of another superpower. While Bhutan never officially joined, the warming of relations has continued with another Chinese delegation visit in January-February 2019, though the countries still hold no official diplomatic relations.

While Chinese diplomats attempt to woo development planners in Thimphu, the People’s Liberation Army (PLA) is only becoming more aggressive. Despite official disengagement, the PLA moved into Doklam again in late 2017. In January 2018, the American geopolitical intelligence company Stratfor released satellite images of PLA infrastructure buildup that would allow 1,600 to 1,800 troops to weather the harsh Himalayan winter. While a second standoff has yet to occur, India has increased military presence along the Indo-Bhutanese border, with both countries building up their air power nearby. By March 2018, the issue rose to prominence once again, with Indian defence minister Nirmala Sitharaman confirming that both sides “redeployed themselves away from their respective positions at the face-off site.” Though she added that the “strength of both sides has been reduced,” images confirmed that China had built a new road deeper into Doklam, away from the Indian post. This bold move seemed to challenge India—it would require a far larger military action to counter.

Since then, the buildup has only increased, with a January 2019 report showing that the PLA has nearly completed an “all-weather” road in Doklam, another sign that Beijing is determined to claim Doklam despite its challenging landscape. At the same time, Delhi announced the construction of 44 “strategic roads” along the Chinese border, a move that hints not only at Doklam but the greater Sino-Indian border struggle.

These border buildups have made one thing clear—the heart of the issue goes beyond Bhutan. In a dispute over land it claims, where is its agency? Bhutan has taken assertive steps of its own, navigating the delicate balance of an age-old Indian friendship and complicated Chinese relations. From Doklam to Dantak, Bhutan has been subject to a little-known weapon of war: roads. Can the small country play the two superpowers, or is it doomed by their battle for continental dominance?

Photo: “Map of Doklam“