These days, recycling is out, and recycling cynicism is in. In 2017, that cynicism peaked when China axed a decades-long agreement to purchase American recycling. This left environmentalists, policymakers, and concerned citizens wondering: could Americans adapt, and deal with their own recycling, or would most of what we “recycle” end up in the trash?

For example, how much of the aluminum, steel, iron, and glass in Seattle—a city that regularly touts its environmentalism—is actually recycled in Seattle? That’s right: All of it. Wait…what? Indeed, Seattle’s success in adapting to the new recycling landscape contrasts starkly with news headlines such as “Is This the End of Recycling?” and “Since China’s Ban, Recycling in the U.S. Has Gone Up in Flames.” Seattle, alongside other cities and states across America, is pursuing an ambitious zero-waste program. In the face of doomsday predictions, these places lead the country in material recovery rates and prove that recycling can still work. To get there, we must focus efforts on local engagement and public outreach.

The benefits of recycling are extensive, ranging from pollution reduction to energy savings to economic stimulus. For example, recycling petroleum-based plastics provides an alternative to new extraction, thus protecting the environment from damaging drilling processes. Moreover, manufacturing products with recycled aluminum as opposed to new aluminum reduces energy consumption by 95 percent, helping the environment while saving companies money. As for the economy, the National Resources Defense Council estimates that diverting 75 percent of solid waste would create 2.3 million jobs by 2030.

Given these benefits, it is concerning to see a decline in American recycling following China’s “National Sword” decision, the official name for China’s recycling ban. The media’s doomsday headlines do in fact reflect a trend. In what seems like a direct consequence of National Sword, recycling plants across the country are shuttering, and cities are reducing the scope of their recycling plans—sometimes eliminating them outright. Philadelphia, for example, identified neighborhoods with high contamination rates and began sending their recycling to an incinerator earlier this year. Meanwhile, Deltona, Florida suspended its curbside recycling program due to high costs. Though nationwide assessments of waste management are lacking, one projection from the Plastic Pollution Coalition—an alliance of organizations and businesses “working toward a world free of plastic pollution”—estimated that overall recycling dropped by 4.4 percent in 2018.

But not all is lost. In some cities, this dismal trend doesn’t hold. Seattle, for instance, has maintained meaningful waste reduction since China’s ban, achieving all-time per-capita lows for the last two years. On an average day in 2018, the average Seattleite threw out about 2.16 pounds of waste, compared to the U.S. average of 4.4 pounds. Individual states have made positive strides as well. In Vermont, statewide recycling by weight rose slightly from 2016 to 2017, despite rising costs throughout the recycling industry.

To figure out how these governments are defying the recycling depression—and to learn from their successes—we need to consider how they counteract two barriers to effective recycling: a lack of citizen participation and recycling contamination (when dirtied or non-recyclable items force cities to redirect recycling collections to the landfill). Certainly, citizens must understand their city’s recycling programs, and they must actively recycle for state or city programs to do any good. For example, plastic bottles are one of the easiest materials to recycle, but only an estimated third of them make it into recycling facilities due to improper disposal. Contamination also leads to higher costs, as workers must spend more time sorting recyclable material from non-recyclable. One major cause of contamination is “aspirational recycling,” or the practice of putting non-recyclable materials into the recycling bin. The pitfalls of contamination are undeniable, and they even played a role in China’s National Sword decision; China set a maximum contamination rate of 0.5 percent, yet U.S. contamination rates reach as high as 25 percent.

However varied, state and city approaches to these challenges have a uniting principle: the realization that solutions tend to come from local engagement with recycling programs. In Vermont, much of the success in fostering recycling participation can be attributed to a 2012 statewide ban on recyclable materials in landfills and to mandatory composting and recycling policies. The government also requires waste haulers to offer compost and organic waste services, and it mandates that edible foods be donated if possible. It seems to be working: Food scraps diverted to composting facilities rose by nine percent from 2016 to 2017.

Similarly, San Francisco requires property owners and managers to provide differently colored bins for compost, recycling and trash, and it enforces the policy with fines. As a result, San Francisco has the lowest per-capita landfill waste in all of the U.S., with just 1.5 pounds of landfill waste per person per day. That’s a diversion rate of around 80 percent.

Put simply, recycling mandates work. Still, some balk at the severity of a mandate, advocating instead for an incentive-based model designed to nudge, rather than force, participants towards better habits. Seattle, which has a more leniently enforced recycling mandate—single family homes pay a one dollar fine if more than ten percent of their trash is food material—supplements its mandate with a carefully considered set of financial incentives. In this system, citizens pay for the trash they produce by weight, while they pay no fees to recycle.

As for contamination, which is a direct consequence of confusion or misinformation, information campaigns can be transformational. In a coordinated outreach campaign, Seattle sends regular newsletters to residents on sustainability issues, including what to recycle, how to recycle it, and what exactly happens to their recycling when it leaves the curb. City officials have also conducted interviews with local news and radio stations to broaden the reach of these messages. So far, the city is optimistic about the impact of the approach.

Taken together, the most effective recycling strategies—from Seattle to Vermont, from recycling mandates to media campaigns—are based on the understanding that local engagement with citizens works. The results are clear: The most stable regions amidst the recent recycling uncertainty are those taking a local and engaged approach.

China’s National Sword tests our commitment to and capacity for recycling. If the U.S. still wants to make recycling work, we can. We just need to look to the cities and states that are weathering the storm.

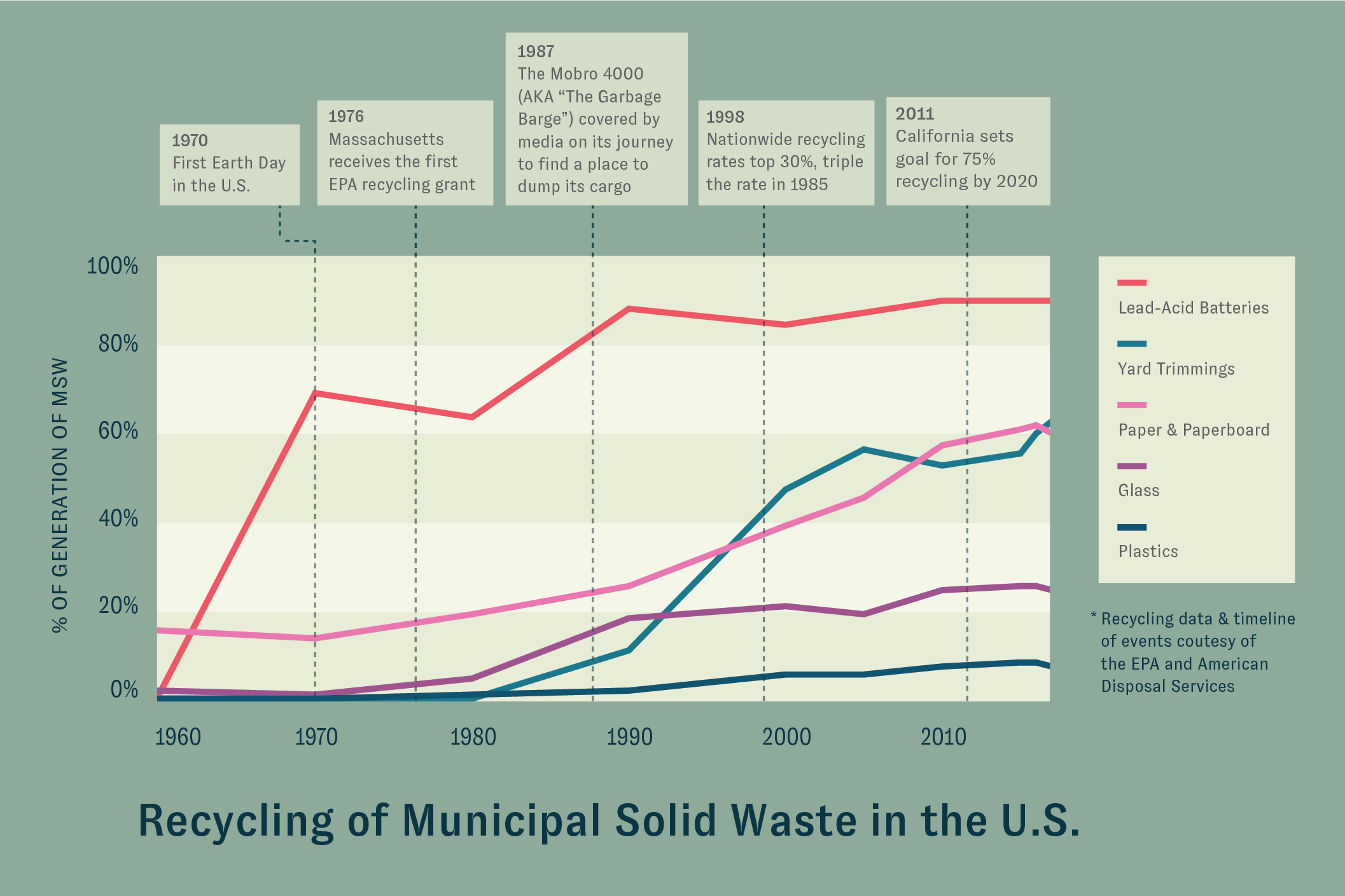

Infographic by Minji Koo ’20, data by Emilia Ruzicka ’21