As of February 9, 2020, the Coronavirus outbreak has claimed over 600 lives and infected over 80,000. The figures have surpassed the SARS outbreak in 2002-3, which claimed 774 lives worldwide. One difficulty in containing the epidemic, however, has become a matter of distinction: Where do necessary precautions end and anti-Chinese sentiment begin?

Various countries have implemented travel restrictions on travelers from China after the World Health Organization (WHO) declared a public health emergency in response to the coronavirus. Notably, the United States banned foreign nationals from arriving if they had traveled to China in the past two weeks; Japan, Singapore, New Zealand, and Australia have followed suit. The WHO has also emphasized countries should not impose travel restrictions given that researchers have found blanket bans can only delay but not contain outbreaks.

With infections doubling every four days, China has intensified its quarantine of Wuhan. Medical workers are to visit all homes in Wuhan and check resident temperatures, and the sick are immediately transported into makeshift quarantine hospitals converted from stadiums, exhibition centers, and building complexes. Overwhelmed by the number of patients, the makeshift hospitals struggle to keep up and are running out of supplies. With transportation systems shut down, today, over 50 million people who live in Hubei province are unable to leave while feeling they have been abandoned by the rest of the country.

Outside of Wuhan, Chinese officials are sealing off more cities every day and people fear going outside in case of coming into contact with those infected. The Chinese Communist Party (CCP) has expended significant resources to contain the spread, and the country’s decentralized governing system has posed challenges to a collective management plan. As Zhou Xun, a professor at the University of Essex said, “A perfect plan on paper often turns into makeshift solutions locally” and “can be quite haphazard.” Laudable efforts include building a hospital from the ground up in 10 days, but physically locking people indoors to force quarantine in Zhejiang, or banning the sale of cold medicine in Hangzhou pharmacies to force people to go to hospitals is inappropriate.

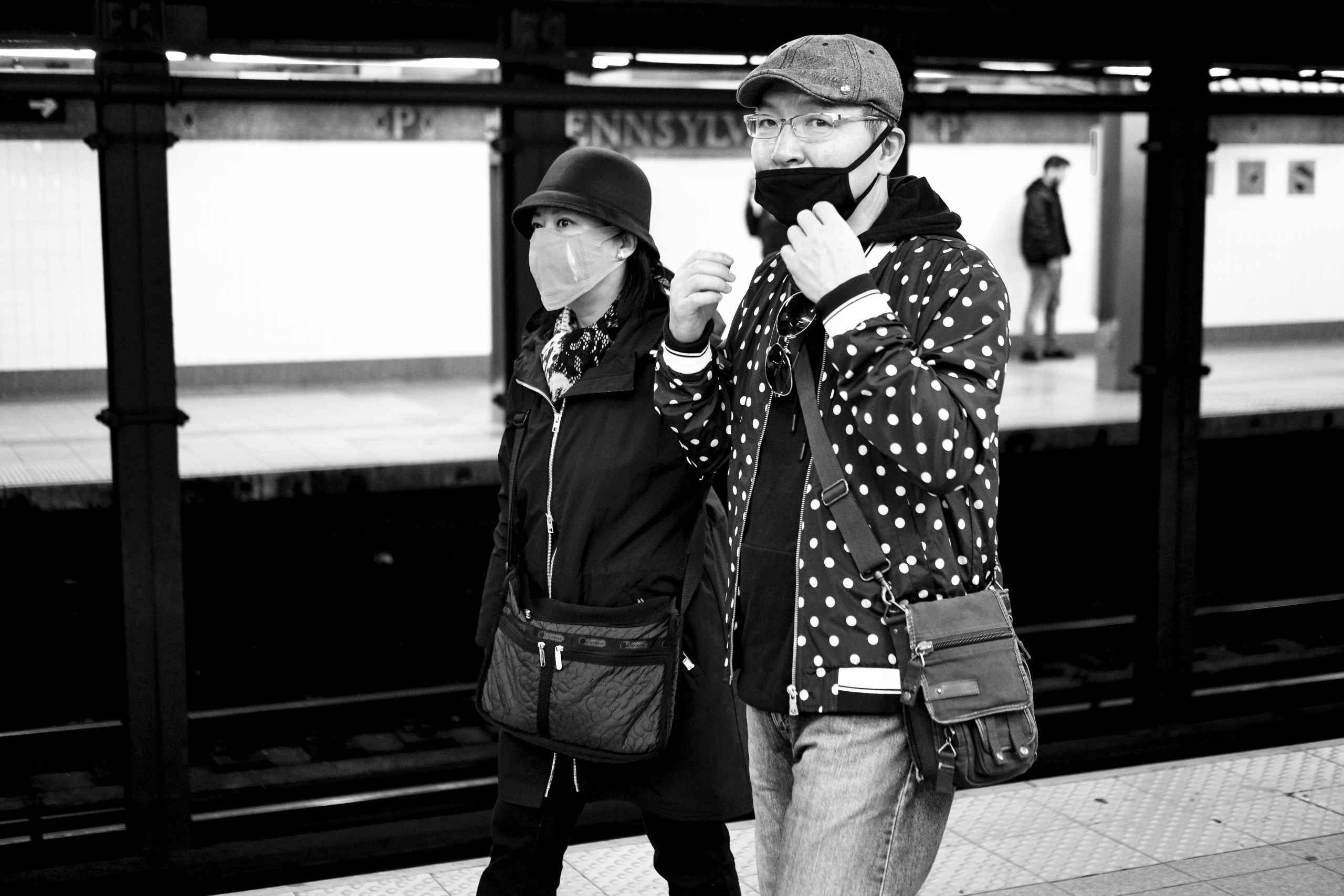

With the increase in necessary precaution efforts, however, xenophobic sentiments are also spreading rapidly around the globe. In Indonesia, protesters rallied against the presence of Chinese tourists in a local hotel, #ChineseDon’tCometoJapan is trending on Twitter, a Danish newspaper replaced the Chinese flag with viruses over stars, and a French newspaper published the headline “Yellow Alert”. On college campuses in the US, students have reported feeling anti-Chinese sentiments and being hyper-aware of their Asian ancestry. Many Asian students have reported uncomfortable looks from their peers when they sneeze or cough due to a common cold, while others have experienced attacks and racist comments in public spaces. UC Berkeley’s health center went as far as posting “xenophobia” towards Asians is an understandable response to coronavirus, along with anxiety and sleeping issues.

The virus, believed to have stemmed from wild animals at a food market, has also fueled many racist remarks about Chinese people’s eating habits. This type of discriminatory behavior invokes past racial stereotypes tying orientalism to disease, reminiscent of an 1854 New York Daily Tribune article that claimed Chinese were “uncivilized, unclean, filthy beyond all conception.”

Many Chinese communities are still experiencing a collective fear in recalling the SARS outbreak, during which the government downplayed the extent of the disease. One immigrant from Hong Kong who now lives in Vancouver describes the ritual he and his wife had during the outbreak. They would remove their N95 face masks and strip down in the doorway, then put all clothes in the washing machine with Dettol and showered immediately. However, this history is either unknown or ignored in the West. The United States has little lived experience related to outbreaks, and many do not have family members or friends to worry about in China.

The recent display of anti-Chinese sentiments—for example, poking fun at face masks—cite illegitimate fears in a way that ignores past trauma of SARS amongst immigrant communities, mainlanders, and Hong Kongers. In Hong Kong, however, wearing face masks regarded as an act of collective solidarity; even children in elementary schools were required to wear them. York, an immigrant community in Toronto affected by SARS in 2003, warned against xenophobia towards Chinese people. The statement issued by the school board read: “While the virus can be traced to a province in China, we have to be cautious that this not be seen as a Chinese virus…At times such as this, we must come together as Canadians and avoid any hint of xenophobia, which in this case can victimize our East Asian Chinese community and we must rely on our shared values of equity and inclusivity.”

Travel bans not only threaten the moral standing of Chinese communities abroad but may also have serious implications for China’s economic future. Amidst a trade war and future political uncertainty towards China’s role in the global economy, broader fears of the virus seem to be suggestive of general anxieties about China’s rise as a world power: US Commerce Secretary Wilbur Ross said the virus could bring jobs back to the US. Although Democrats and economists have been very critical of Ross’ comments, the Commerce Secretary is right about the US economy being affected in some way or another by the coronavirus panic.

In addition to the travel ban propagating racist sentiments towards Chinese people, the economic blow travel bans may catalyze is a shock to the Chinese supply chain, an event that has immense ramifications for much of the world. With the largest car market in the world, China shutting down factories threatens production chains in the rest of Asia, North America and Europe due to the lack of component parts. Worldwide, eight million people are employed in the auto industry, and various car production companies––BMW, Toyota, Hyundai, Daimler, and Volkswagen––have all temporarily closed factories in China. If the virus is not contained, the effects could cripple the auto manufacturing process and result in losses of sales in other industries such as textiles and computer parts.

While public fears about the disease are reasonable, taking them out of proportion and at the expense of Asians is not. In the wake of the SARS trauma, and considering the long history of yellow peril and racial policies that found justification in framing the Chinese as disease-bearers, the public ought to be more sensitive in discussing and understanding the coronavirus. With serious economic implications set in a context of uncertainty about China’s future, the virus should not be taken lightly and must not be portrayed as a Chinese disease. Taking measures of precaution should not come at the cost of others’ humanity.

Photo: Image via Flickr (susanjanegolding)