Vera Molnár, considered by many scholars and historians to be the world’s first female digital artist, began her career in the mid-1940s. Born in Budapest, Hungary in 1924, Molnár started creating art at eight years old and went on to obtain BFAs in both Art History and Aesthetics at the Budapest College of Fine Arts. In 1947, Molnár moved to Paris, France where she met her husband, François Molnár, and began to experiment with graphic plotter drawings at a computer research lab after learning several coding languages.

Molnár, also known by her maiden name, Gaks Vera or GV, had already established a body of conventional work when she began creating computer art. She continues to utilize traditional media as well as and as part of her digital pieces to the present day. Curators have compared Molnár’s work to Cézanne’s. Inspired by Mondrian, Malevich and the concrete art movement, she has acknowledged a passion for “exact science and mathematics” with “a hint of disorder” in her constructivist computations. A question about her has been included on the French baccalauréat exam. Molnár’s art is regularly exhibited in museums, art fairs and galleries worldwide. Recently, she was showcased in the Museum of Modern Art (MoMA)’s 2018 group exhibition Thinking Machines: Art and Design in the Computer Age. Her work has been featured in The New York Times, artnet News, CNN, Hyperallergic, and Forbes, among others. Now 96 years old, the artist continues to live and work in Paris.

*Molnár’s responses were given in French and kindly translated to English by BPR contributor Rose Houglet.

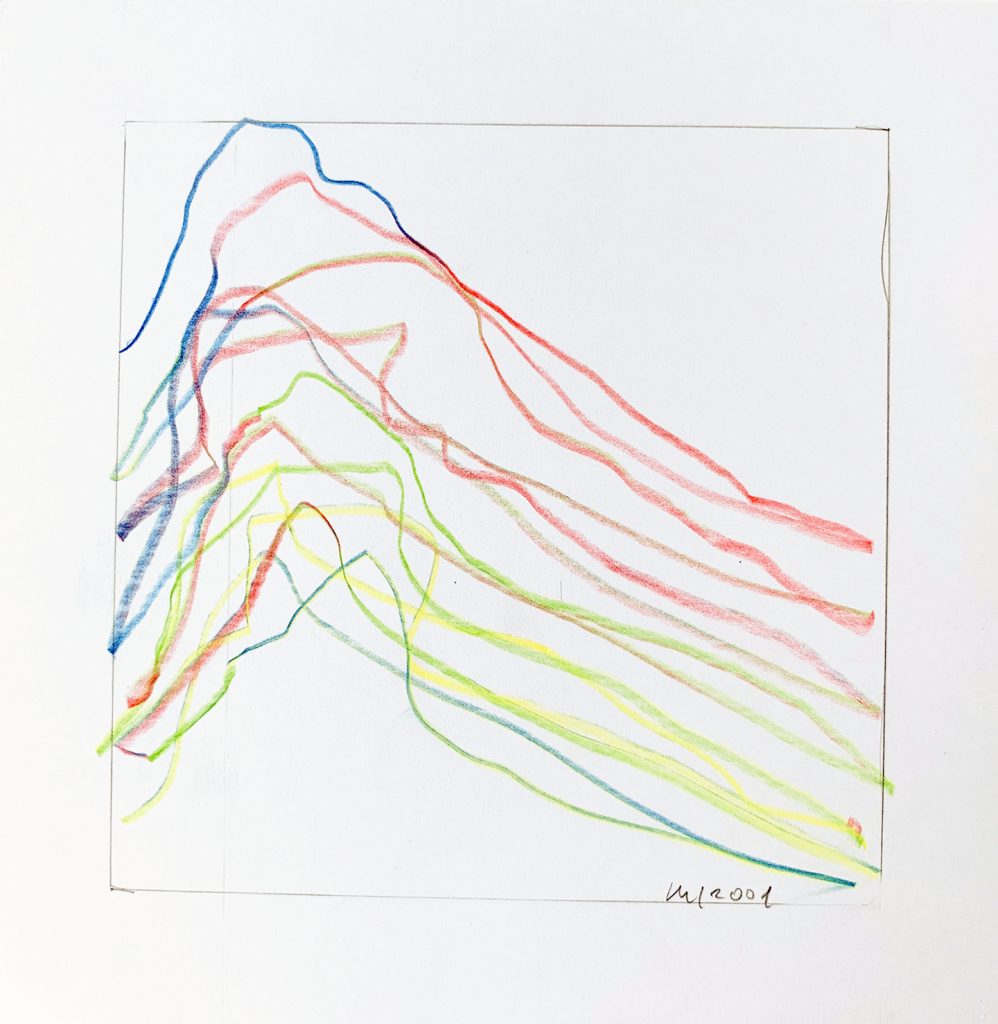

Amelia Spalter: Perhaps one of my favorite illustrations of your creative process is the evolution of your relationship with Montagne Sainte-Victoire. Could you describe how it became such a prominent symbol in your work?

Vera Molnár: I was in the United States with my husband, who worked in a laboratory, and I had some spare time. So, I went to a library in between MIT and Harvard. I was at a point in my life where I had had enough of the square, the circle, the rectangle, square, circle, rectangle, square, circle, on and on. [It was in this library] that I stumbled upon Gauss’s curve, and I told myself, “I could like this Gauss’s curve, with its symmetry and touch of disorder.” I liked the combination of classical straightness with a drop of madness. I made a pile of drawings and was content with the sentiment that I had fallen on the year’s best idea: no more circles, no more ellipses, no more squares. I wrapped my pile of drawings in a towel. Then, on our last night in the U.S., we stayed in a hotel in Philadelphia, where someone stole the towel. There was nothing of value inside — no money or plane tickets — only two months’ worth of work by my husband and me. All of my Gaussian curves. I was furious, and so I said, “I will go back to squares and rectangles, and I don’t want anything to do with Gaussian curves.”

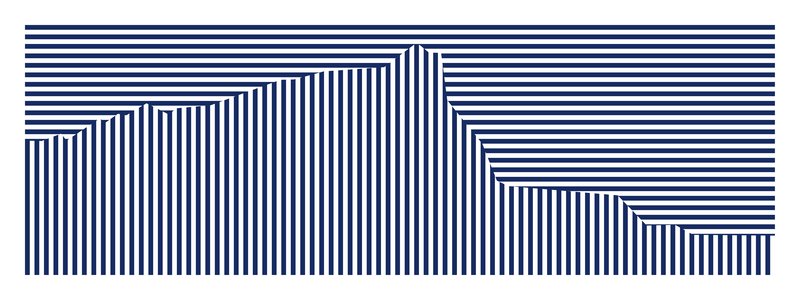

Ten years passed, fifteen maybe, and I had an exhibition in Aix-en-Provence. I opened my shutters, and what do I see? The Gaussian curve through Mont Sainte-Victoire. For once in my life, I had no pencil or drawing pad — which usually I always do — but for once I had nothing. I found a piece of scrap and scribbled it down, I might even still have the original somewhere. I have baptized the curve “the Sainte-Victoire Curve,” and people understood that I was referring to [Cézanne’s] Mont Sainte-Victoire. It does not have that much to do with Cézanne, though maybe it is that I saw it on all his paintings that represent the mountain. I’m not sure, but in any case, it has remained one of my favorite subjects.

AS: You began creating art professionally in the 1940s. Do you feel the growth of your career was in any way stunted by the misogyny of that period?

VM: No, truly not, truly not. I was able [to work on my art full time] because my husband thought that I should be a homemaker while we both lived on his salary. In between cleaning two dishes, I could always make squares. So, it is because of my sad status as a housewife that I could paint. If I had been working outside the home, teaching or something of the sort, it would have taken up all my headspace. So, no. I tell people that two machines helped me to succeed: the computer and the dishwashing machine.

AS: What was your family’s reaction when you told them of your plans to go to art school?

VM: I remember one morning when I was 16, I said, “Mom, there are some things that I want to tell you: First, I don’t want to play piano, I want to paint. I don’t want to go to church. I don’t want to wear glasses. And finally… I want to make my life in France.” My poor mother, it hit all at once. But she was an intelligent woman. She told me, “All right, well, there is one thing that is non-negotiable, it’s the glasses. You have bad myopia, and you will get crushed by a car. The rest we will talk about when you come back from school. Now put on your glasses.” And she was right, I still wear my glasses.

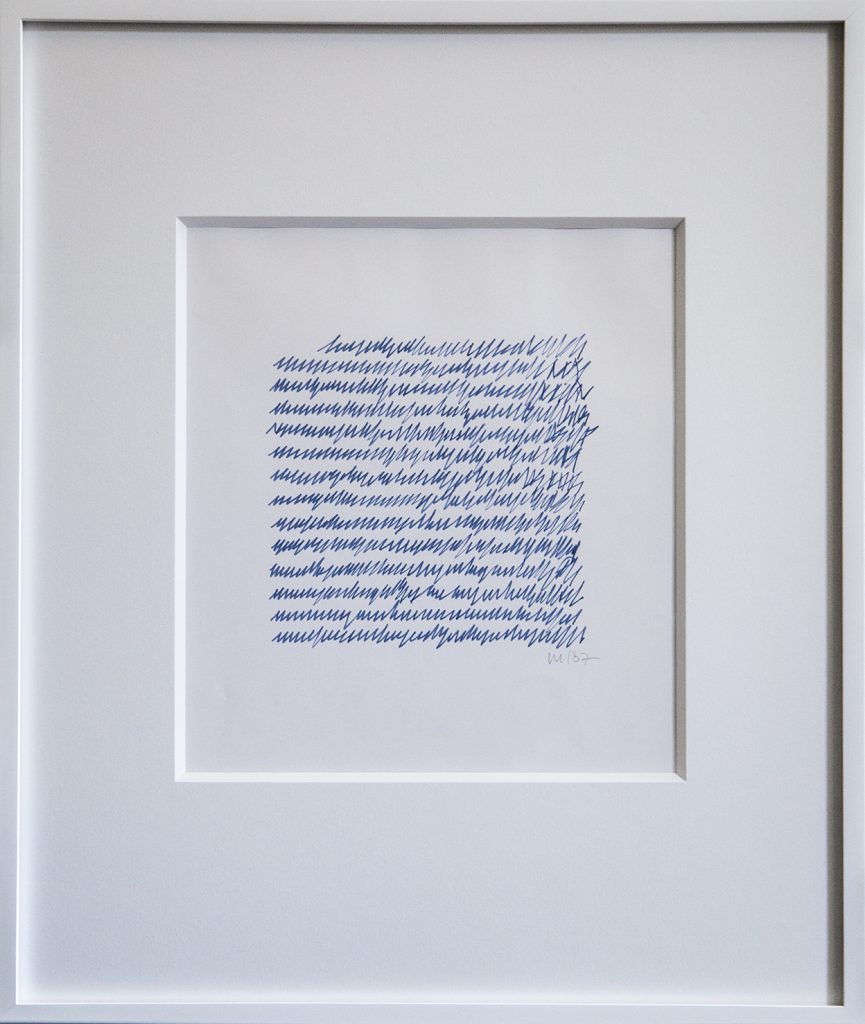

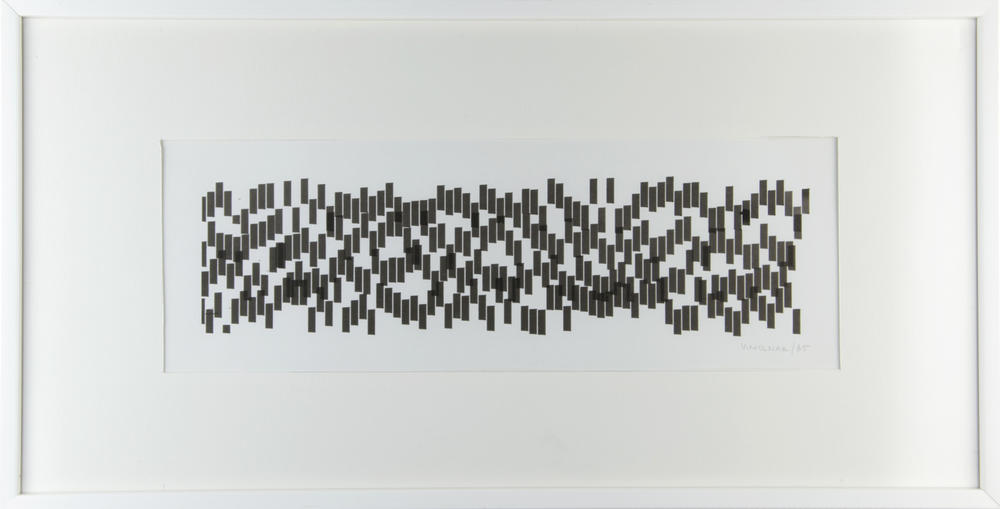

From a series exploring the geometric structure of handwriting, based on weekly letters the artist received from her mother.

AS: Who was your greatest influence as a young artist?

VM: The first female artist whom I met and who had a huge influence on me was Sonia Delaunay, when I was in France. My husband and I arrived in France in 1947, and we were hungry and had no money. Once a week, always on a Wednesday, we could go to Sonia Delaunay’s house [to show her our art,] and there was tea and as many little cakes as we wanted. Her art was magnificent, elegant, beautiful, sort of like what is showcased today at Galerie Thaddaeus Ropac. My work was dirty, and not done very well. But she told me, “This young lady, she will go far, if she works very hard.” I thought to myself, “If Sonia Delaunay tells me that, then… wow.”

AS: How do you feel the Nationalist-Socialist setting of your art school education in Hungary influenced your later work?

VM: In Hungary, there was the Nationalist-Socialist environment, and no modern art. The day after the war, everything changed concerning fine arts. At the art school where I studied, during the war everyone was a Nazi, and immediately afterwards they were all Communists. But we had a French professor who was a secretary for Jean Cocteau, and he brought us reproductions of Matisse in color. I was not used to things like this; at the time, one had to create popular paintings in neutral colors. After seeing Matisse, I did [performance art] for the first and last time. I went with a bunch of friends to the Danube River, and threw my black paint tube in the Danube, saying that I never wanted to use it again. Today, black is my favorite color.

AS: Did growing up in such a turbulent, often depressing political era contribute to your desire to work in the abstract?

VM: It happened little by little. I painted like a young wealthy girl — portraits of my mother, of a cow — but without passion. And then, I encountered Cubism, which was a decisive moment for me. Cubism, as a painting style that is figurative but constructive at once, helped me. So, I wasn’t entirely giving up nature, but I stayed in the abstract, even though I didn’t know Cubist icons like Mondrian or Malevich yet. Cubist painting pushed me to where I am today.

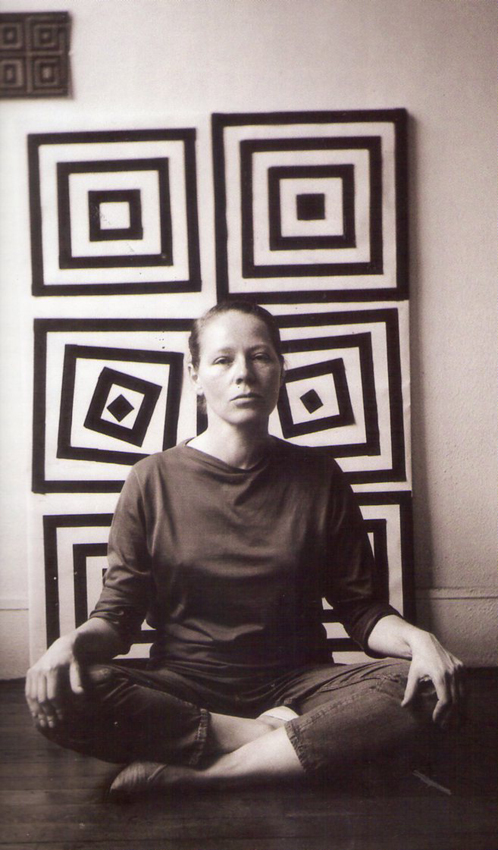

One of an expansive series on quadrilateral structures.

AS: You have been a professional artist for over 70 years and counting. What is the most unexpected way some of your works have come to be interpreted over time?

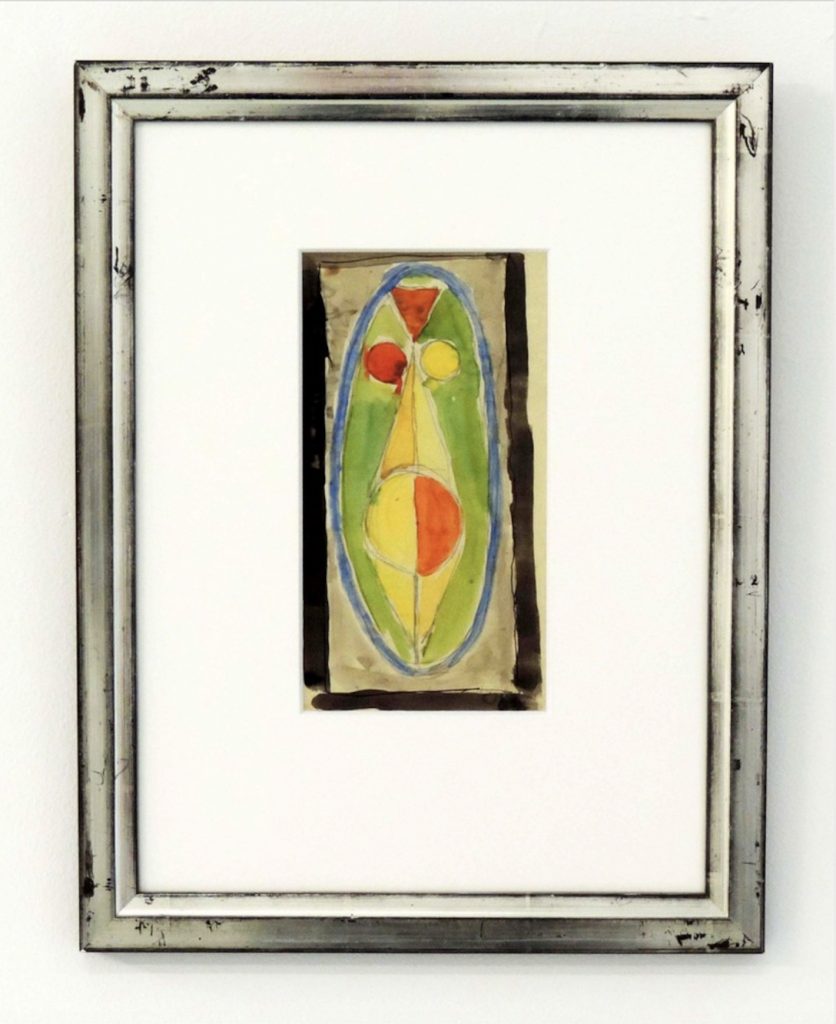

VM: A big adventure of my life as a painter was that when I was young, I designed a greeting card every year, which I innocently sent to all my friends. One day, I was invited to have dinner at my husband’s colleague’s house. They had a little boy who told me, “Come to my room, I’m going to show you something.” I went to his room, and what did I see on his wall? All of my greeting cards from years past. I was very happy, of course, to see a kid who took them very seriously. Recently, I received a little note with photos from him. He is now a grown-up Hungarian collector who is showcasing all of my small-format works in the style of greeting cards in a gallery in Budapest. I think that this man is doing amazing work, because these are pieces that would otherwise be thrown away. He is a watercolor specialist who became a big collector, and the little things in his show are both personal and intemporal.

at the MoMA.

Courtesy of the Museum of Modern Art

AS: You’ve said your favorite part of making computer art is the element of surprise. But when you first began working with computers, most did not have screens. When screens became the norm, did you feel digital work lost some degree of surprise?

VM: Oh no, that was when it became magical. All of a sudden, you could see in front of you exactly what was happening in your head. I was born a second time with the visualization of the screen. It was fantastic for me, because normally we imagine something and start drawing and then it’s not what we wanted, so we rip it up and repeat this process until we become tired after the 125th attempt. It’s like visual psychoanalysis.

I think the screen was invented for me. The scientists didn’t need it, because they could wait a day to see their calculations. But to see a square that transforms itself bit by bit into a trapezoid, the screen is crucial. Because for a very long time, the eye was used to only seeing a square when we saw a square. A trapezoid is almost a square, but with the computer, I was immediately able to see the exact moment when a square was no longer one. Still today, I love painting things where we can’t see what the original object was. For example, we were talking about Mont Sainte-Victoire. In my pieces, you cannot actually see Mont Sainte-Victoire; there are parallel lines, but nothing else.

Courtesy of Artspace

*This interview has been edited for length and clarity.