Silicon Valley has a secret. Beneath its comically unaffordable real estate lie 23 federally designated sites of toxic waste, 8 more than in any other county in the US. In the past 40 years, just one site has been fully decontaminated.

Even here, in one of the wealthiest places in the world, the Environmental Protection Agency’s (EPA) Superfund program has failed to address the problem of toxic waste. Established in 1980, the program was supposed to identify and monitor the cleanup of highly contaminated sites. The program showed promise at first, with hundreds of sites identified each year. Since then, however, its productivity has slowed, due in large part to EPA managers’ unwillingness to add potentially costly sites to the National Priorities List. Other problems plaguing the program include a lack of funding, regulatory malaise, and the opposition of corporate “potentially responsible parties” to paying their mandated share of the cleanup bill. If Superfund is to ever effectively address the problem of lingering industrial waste, it must rehabilitate its internal inefficiencies, seek additional funding by bolstering its ability to collect damages from corporations, and invest in research infrastructure to identify sustainable cleanup methods.

Tar Creek, a Superfund site in northeastern Oklahoma, is a case study in the negative effects of toxic waste contamination. Due to aggressive lead and zinc mining in the early and mid-twentieth century, the site is one of the most toxic areas in the US today. Even though mining operations ceased in 1970, Tar Creek still exhibits many of the symptoms of chemical poisoning. The banks of the area’s creeks are colored by orange water, and enormous piles of “chat,” or mine pilings, are scattered around the town. The effects on the residents of the town have been severe: One 1996 study found that 30 percent of children under the age of six living on the site had elevated levels of lead in their blood, rendering them more vulnerable to learning disabilities and experience issues related to the development of their nervous and immune systems, among other health problems.

The Tar Creek story demonstrates both the devastating effects of Superfund’s recent failures and the pressing need for reform. Although the area became a Superfund site in 1983, it wasn’t until 2006 that the EPA organized a federal buyout of the region, compensating Tar Creek residents for their toxic, unlivable property in an effort to vacate the area. So why did it take so long?

One answer to this question is Superfund’s lack of funding. When the program was established, Congress created a trust fund by taxing the petroleum and chemical industries to finance Superfund activities. However, Congress opted notto renew the tax in 1990, and it expired in 1995. Since then, the program’s funding has mostly come from state taxes and congressional appropriations from general revenue; its federal funding has declined from roughly $2 billion in 1999 to $1 billion in 2013. Both independent consultants and the EPA itself have suggested that a lack of funding, which has caused a shortage of full-time employees, has stalled Superfund efforts.

Another problem with the Superfund program is its inefficient self-regulation. One of Superfund’s popular cleanup methods is called “pump-and-treat” (P&T), a process by which contaminated groundwater is pumped to the surface and transported to a secondary facility for treatment. This method is slow and environmentally unsustainable: It produces roughly 20,000 pounds of carbon dioxide for every five pounds of contaminants it processes. Alarmingly, this might not even be an accurate estimate. The EPA itself admitted that emission estimates are “self-reported” and not necessarily “[supported] by measurements,” which means the EPA lacks even the most basic data to make informed choices about sustainable cleanup.

Furthermore, the EPA has conducted multiple studies that expose hundreds of problems with conventional P&T systems but has yet to replace these systems with more effective solutions. This inaction can be partially explained by the fact that more effective methods haven’t been invented yet; in addition to investing in studies that expose the issues with P&T, the EPA should begin to channel funds towards developing alternate technologies. The EPA must also address the fact that its metrics of measuring progress may be flawed. For contaminated sites, Superfund’s standard for a successful cleanup—drinkable groundwater—is often functionally impossible to reach: One environmental consulting firm suggests that it will take 700years for Silicon Valley’s Superfund sites to achieve said benchmark. Furthermore, the current Superfund model fails to effectively incentivize sustainable cleanup methods, as these projects are usually funded and directed by the corporations deemed responsible for the waste rather than by local stakeholders. In Tar Creek, for example, the EPA has refused to recognize the Quapaw Nation’s right to oversee cleanup of its own land.

While funding and regulatory hurdles have plagued the Superfund program for years, cases of corporate irresponsibility within the program have recently been thrust into the spotlight. In December of 2019, the Supreme Court heard arguments for the case of ARCO v. Christian, in whichMontana landowners Christian et al. sued the oil company Atlantic Richfield Co. (ARCO) for state-law restoration damages “to restore their property to pre-pollution status.” In response, ARCOargued that the Superfund Act forbids external parties from seeking remuneration for an EPA-mandated Superfund site. According to ARCO, the EPA should have the right to determine whether hazardous waste removal is “technically impractical” or worth the cost, and landowners should not be considered “responsible parties” with the right to drive cleanup decisions. If ARCO loses, the company claims, the entire Superfund program will devolve into “chaos.” The landowners, on the other hand, have argued that because “nothing has been done” to mostof the affected land, they should have the ability to pursue rehabilitation of their own property. Unfortunately, it seems that the Court is leaning toward a narrow, business-friendly ruling along partisan lines which would deny Montana landowners the ability to seek remediation in state courts, just as the Quapaw Nation was denied this ability in the case of Tar Creek. This example speaks to Superfund’s incompetence in two ways. First, the landowners should not haveto seek additional damages–and wouldn’t even need to do so if Superfund had completed cleanup in an effective and timely manner in the first place. Second, ARCO’s ironic abuse of the Superfund Act, originally created to protectlandowners from the financial burdens of toxic waste removal, to oppose Christian et al. shows just how far Superfund has strayed from its original purpose.

Ultimately, Superfund sites are a problem for everyone—rural and urban, rich and poor alike. They affect questions of sustainability, socioeconomic mobility, and environmental justice. More than one in six children under the age of five will grow up within three miles of a Superfund site; more than one in ten Americans below the poverty level live within just one mile. The US must pursue aggressive reform to create a functional program or risk poisoning a generation of its people.

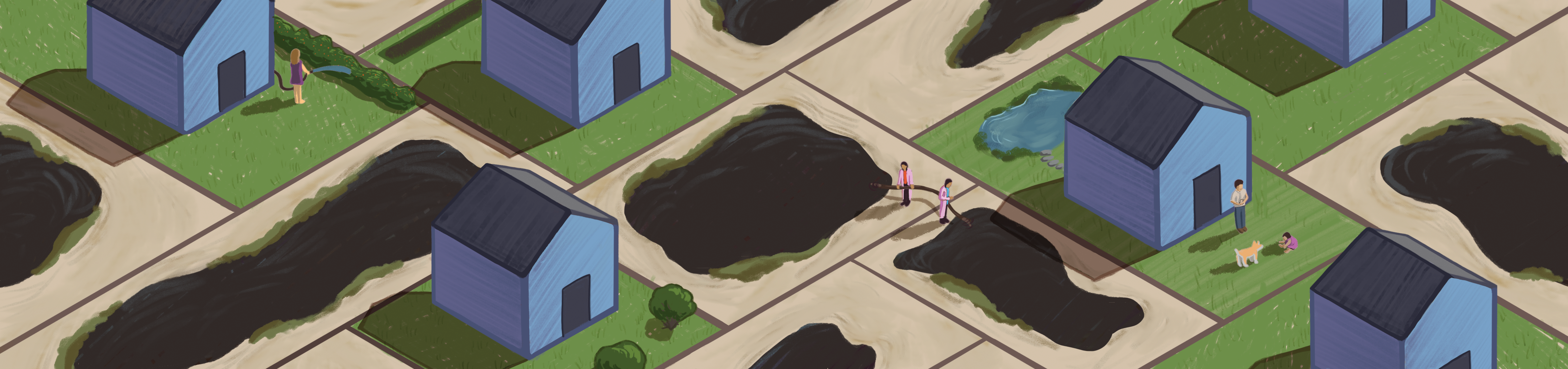

Illustration: Kira Widjaja ’20