“Give me your tired, your poor, / Your huddled masses yearning to breathe free, / The wretched refuse of your teeming shore.”

Today, US asylum policy is a far cry from the open approach described in Emma Lazarus’s poem inscribed on the bottom of the Statue of Liberty, a universal symbol of justice and freedom.

The United Nations, via the 1951 Refugee Convention and the 1967 Protocol, defines a refugee as a person who is “unable or unwilling to return to his or her home country, and cannot obtain protection in that country, due to past persecution or a well-founded fear of being persecuted in the future on account of race, religion, nationality, membership in a particular social group, or political opinion.” The United States Congress incorporated this definition into US immigration law in the Refugee Act of 1980. This definition includes an omission with alarming implications: There exists no legal basis for asylum for those suffering from economic persecution in their home country. Modifying this definition to include refugees fleeing large-scale economic devastation comparable to that caused by war is a moral imperative for the United States. The current Venezuelan refugee crisis illustrates the need for this policy change.

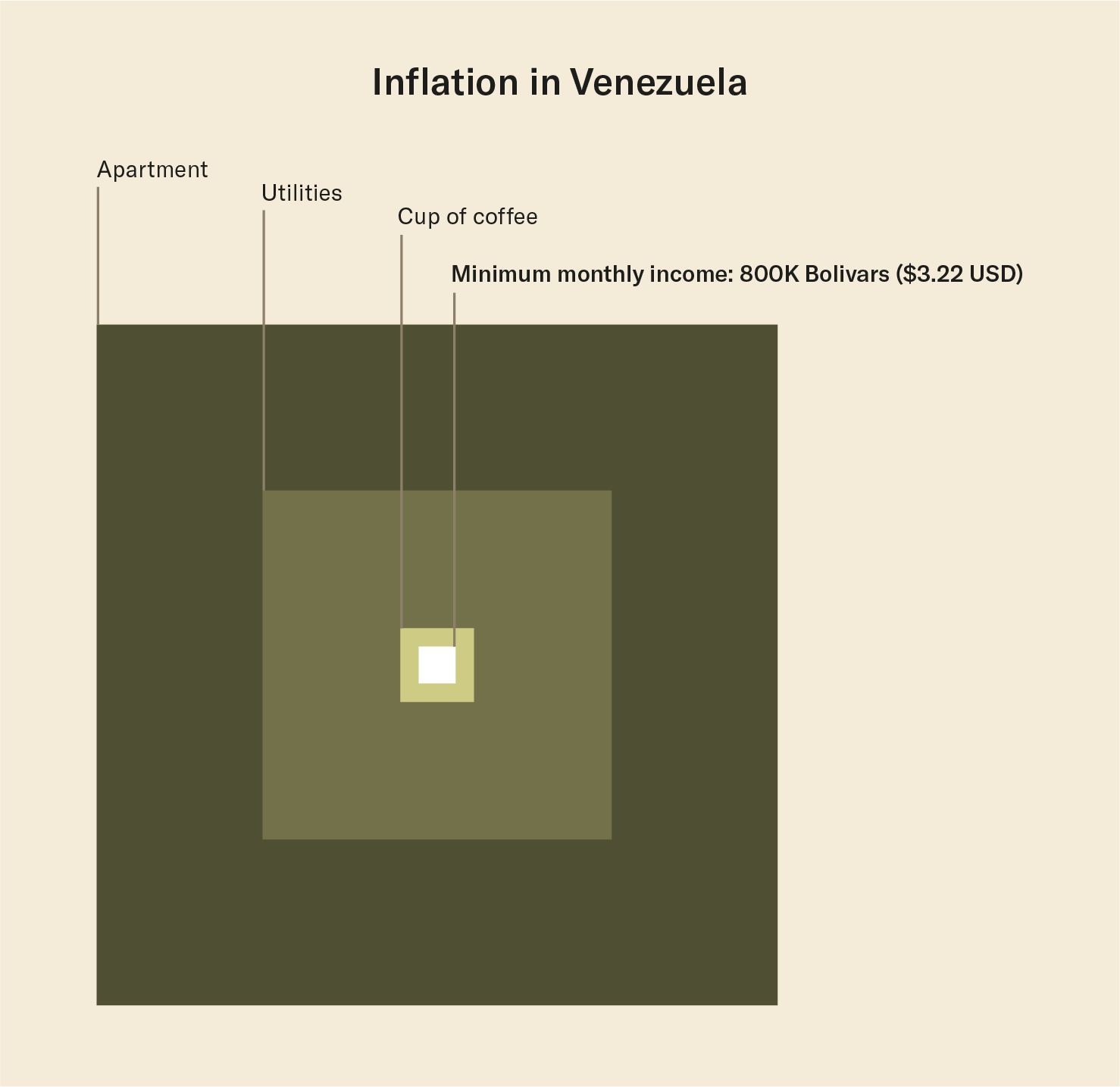

According to the United States Agency for International Development (USAID), there are seven million people in need of humanitarian assistance in Venezuela along with 5.4 million Venezuelan migrants and refugees worldwide, making this one of the largest displacement crises in world history. The economic collapse in Venezuela stands out because it was not triggered by foreign conflict or civil unrest. Rather, it was manufactured by those in positions of political power. The incompetent and corrupt administrations of deceased former President Hugo Chávez and his successor, dictator Nicolás Maduro, have wrecked businesses and livelihoods, triggered exponential inflation, and brought the entire country to its knees. As the country’s economy plummeted, public services collapsed and most Venezuelans were forced to sustain themselves on only a few pounds of flour and animal fat per month. Venezuela’s hyperinflation reached 10 million percent in 2019, resulting in the longest period of inflation since the crisis in the Democratic Republic of the Congo in the 1990s. The annual inflation rate lowered to a still-absurd 2,665 percent in January of 2021. This situation has rendered 96 percent of Venezuelan households impoverished and forced 79 percent of households into extreme poverty.

Although the Venezuelan crisis is not the result of conventional war or conflict, the conditions Venezuelans face daily are not much different from those in active war zones. To find similar levels of economic devastation, economists can only point to countries ravaged by armed conflicts, such as Syria, Iraq, or Nigeria. It is estimated that the drop in Venezuela’s economy under Maduro represents the steepest economic decline in any country not at war in the past 50 years. Hospitals struggle to provide basic services to the malnourished. Unemployed individuals scavenge through dumpsters for scraps of food and pieces of plastic. According to the World Justice Project’s Rule of Law Index for 2020, Venezuela now ranks last in its adherence to the rule of law, including for its restrictions on law enforcement, government powers, and criminal justice. Therefore, the refugees fleeing Venezuela should be afforded protections that align with the severity of the devastation.

Accepting economic refugees into the US is not just a moral decision but an economically beneficial one. When denied legal admission to the United States, most refugees do not return home. Instead, they remain in the country as undocumented individuals, forced to obtain jobs illegally and endure workplaces that violate health codes and minimum wage laws. Despite attempts to enforce sanctions against these refugees, employers continue to hire undocumented refugees, as they tend to work for lower wages than American citizens and accept jobs that Americans refuse. The constant fear of deportation also restricts undocumented refugees in both their daily activities and in their ability to fully contribute to the US economy. In fact, the average adult refugee pays about $128,689 in taxes over their first 20 years in the United States—$21,324 more than the US government’s average per-refugee spending over the same time period. Because the current categorization of Venezuelans as economic refugees makes it nearly impossible for them to obtain refugee status in the United States, the country is largely missing out on such contributions.

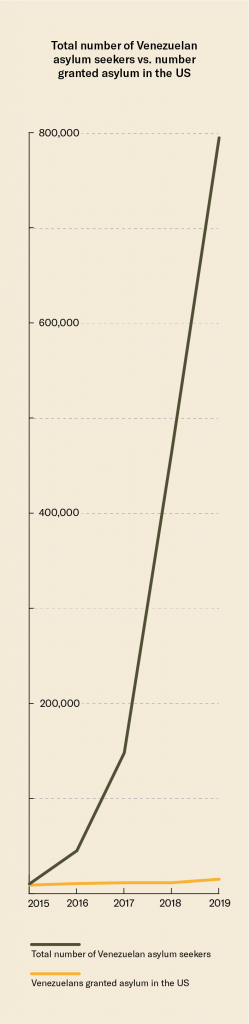

Despite the moral and economic imperatives of addressing one of the worst displacement crises in modern history, the US response has been inadequate. So far, the bulk of hosting responsibilities has fallen on regional neighbors, with the three largest recipients being Colombia, Ecuador, and Peru. Despite the extent of humanitarian need, these countries have received little support from the international community or from the US government. In recent years, other South and Central American countries like Panama, Costa Rica, and Argentina have become some of the primary receivers of Venezuelan refugees. Although the US has taken in about three times as many Venezuelans as Panama, its population is 75 times Panama’s. Part of this discrepancy is due to Panama’s cultural and geographic proximity to Venezuela, but that does not even come close to rationalizing the disproportionately low number of Venezuelans allowed into the United States.

Although US refugee legislation would improve if measures such as Temporary Protected Status and Extended Voluntary Departure were extended to Venezuelans, these laws would nevertheless fail to provide an adequate remedy for asylum seekers. Most economic refugees, such as those fleeing Venezuela, cannot prove that they have a legitimate fear of persecution. The label “economic refugee” is often inaccurate and does not adequately describe the struggles these groups face. Venezuelans, and other groups like them, must be protected just as much as individuals who can prove political persecution. In order to effectively achieve these long-term protective measures, the United States must broaden the definition of a refugee to include those who are fleeing from destroyed economies but who cannot meet the criteria for persecution under its current interpretation.

Because of the existing legal distinction between economic and political refugees, those fleeing Venezuela seldom fall within the scope of existing asylum statutes. Ordinarily, if a person flees their country for economic reasons, they are not considered to be a de jure refugee, or a person unable to return to their homeland. However, this approach lacks rationality. A person may be deprived of basic living necessities in their home country at levels comparable to war, yet still not qualify for asylum status. Therefore, the United States must alter the eligibility for asylum seekers to include those escaping economic oppression to better aid and accommodate those fleeing Venezuela and other future economic collapses. This change in legislation would likely be accompanied by a large uptick in refugees. However, it would certainly be worthwhile in establishing the United States as a leader in ethical asylum reform while addressing the problems facing economic refugees that have been ignored for far too long.