Cuban patriot leader José Martí declared during Cuba’s final War of Independence (1895-1898) that the battle was “the revolution of the doctors.” Indeed, Cuban physicians were ideal conspirators in the effort to overthrow Spanish colonial rule, as the widespread community trust they enjoyed allowed them to discreetly relay communications and smuggle arms and medical supplies for rebels. Some served on the front lines of battle, while others formed organizations in exile to provide the insurgency with material support. Beyond illuminating Cuban doctors’ practical roles in the war, Martí’s words evoke deep connections between biomedical science and Cuban nationhood that crystallized during its independence period. These connections have come into even sharper focus today.

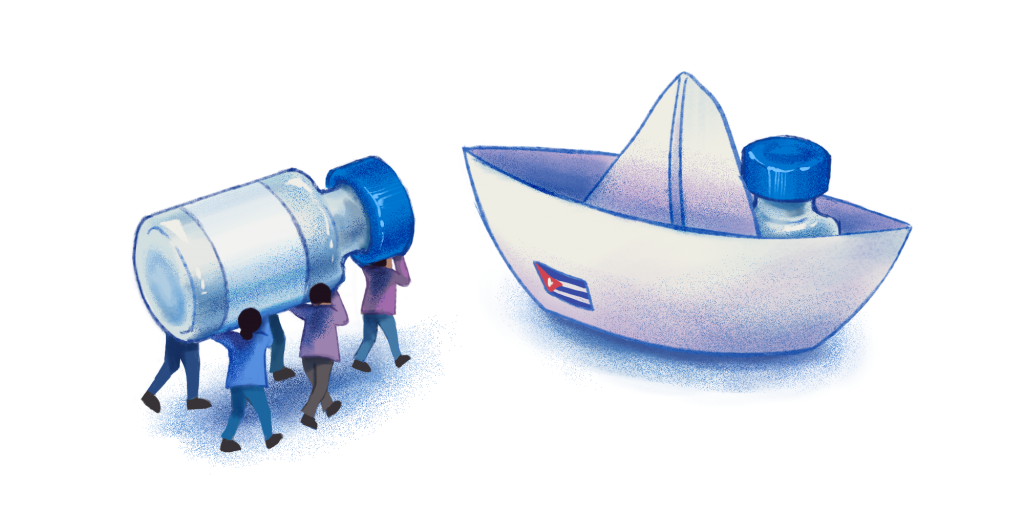

To see this phenomenon in action, look no further than the four Covid-19 vaccines currently being engineered in Cuba: two dubbed Soberana, Spanish for “sovereign,” and the others named Abdala, the name of a poem by Martí, and Mambisa, a reference to the guerrillas who fought for freedom against Spain. In March, Soberana 02 and Abdala began their Phase 3 trials after both exhibited a “potent immunological response” without serious side effects in Phases 1 and 2. Furthermore, Dr. Vincente Vérez Bencomo of the Finlay Institute of Vaccines expected Cuba to have “in the order of 100 million doses” of the Soberana 02 vaccine in 2021, which requires three doses administered at two-week intervals without the need for deep-freeze storage. Once Cuba inoculates its 11 million residents, its sights would turn to the several countries lining up for its vaccines, including Vietnam, Iran, and Venezuela.

For Candace Johnson, who worked closely with Cuban scientists to bring their lung cancer immunotherapy shot to the United States for trials, it was “no surprise” to see Cuba “on the forefront of a [Covid-19] vaccine.” But for those who primarily associate Cuba with classic cars, cigars, and authoritarian communism, news of late-stage Cuban Covid-19 vaccine trials might come as a shock. In actuality, Cuba’s Covid-19 vaccines are the latest examples of medical innovations on the island that reflect an enduring prioritization of citizen well-being that took root during the country’s birth. Cuba’s strong healthcare, biotechnology, and medical education systems, coupled with its long-standing tradition of assisting countries in times of medical crisis, have made it a paragon of medical humanitarianism. Situated in the context of the country’s poverty, these institutions highlight the fact that political will and human capital are more important than wealth in achieving positive health outcomes.

The prospect of Cuba distributing its Covid-19 vaccines throughout the world has brought to the forefront its decades-long doctrine of medical internationalism. The practice is an apparent extension of the Cuban vision of health as a fundamental human right codified in its 1940 constitution. Essentially, it aims to provide immediate disaster relief and medical capacity-building services predominantly to marginalized communities of the Global South at minimal cost to the host country. Since its first team was dispatched to Chile following an earthquake in 1960, Cuba’s medical internationalism program has served 158 countries, where Cuban medical professionals have performed 1.2 billion medical consultations, attended 2.2 million births, and conducted more than 8 million surgeries to date. Recent missions include rapid responses to the 2014 Ebola outbreak in West Africa and the March 2020 Covid-19 outbreak in Italy. When Central America was devastated by Hurricane Mitch in 1998, not only were 1,300 Cuban medical volunteers on the ground within 24 hours, but the Cuban government also granted free medical education to students from affected areas at the newly founded Latin American School of Medicine (ELAM) in Havana. Such a gesture points to Cuba’s strategy of bolstering countries’ long-term medical capabilities in addition to contributing short- term support.

Cynics might explain Cuba’s medical internationalism in terms of economic strategy and notions of soft power. Certainly, the Cuban government accrues significant revenue from medical exports, Cuban doctors are paid higher salaries, and the country itself gains a degree of influence in the Global South because of its altruism. Still, such justifications alone do not square with Cuba’s pattern of offering scarce resources to ideological opponents. This tendency suggests that the country’s motives center around humanitarianism and global solidarity. That Cuba eschews the paternalistic term “aid” in favor of “medical cooperation” is also especially revelatory. In the wake of Hurricane Katrina, for example, Cuba proposed cooperation with the US by sending 1,586 medical personnel and 36 tons of emergency supplies to the country at no cost. The United States declined, being “apparently more concerned with saving face than with saving lives.”

Cuba, however, does not just thrive in the medical field internationally. By conventional measures, Cuba is a poor country, but its approach to healthcare on the domestic level is strong. The fall of the Soviet Union, a primary trading partner, devastated Cuba’s centrally-planned economy in 1991, and material conditions have only worsened due to an ongoing US embargo, sanctions, and Covid-19’s effect on tourism. Despite all these factors, Cuba has consistently had a nearly identical life expectancy and lower infant mortality rate relative to the United States. Such success is largely due to its efficient universal healthcare system. In fact, the system, which focuses on prevention and primary care, has allowed the island to spend just $813 per person annually on healthcare, compared with the US’s $9,403 for comparable results. Cuba’s robust medical education system enables the intensive, personal process of annual in-home check-ups by local family doctors and nurses from neighborhood polyclinics. To make Cuba self-sufficient in the face of trade restrictions impeding the procurement of foreign drugs, the Cuban government invested heavily in biotechnology in the 1980s and spurred the creation of dozens of medical research centers. Consequently, Cuba now holds 1,200 international patents and exports its homegrown biopharmaceutical products to more than 50 countries.

Cuba’s approach to public health on both the domestic and international levels illustrates crucial lessons for improving citizen welfare. As rich countries race to buy Covid-19 vaccines for their inhabitants, Cuban medical internationalism stands out as an exercise in international cohesion and a recognition of our common humanity. In the context of Cuba’s economic woes and its healthcare successes, this tendency indicates that a “political will…to put human beings at the center of the project” is above all the key to promoting the health of a nation and the world at large.